from The Visual Thesaurus http://www.visualthesaurus.com/

Accuracy and fluency: it used to be the case that, of these two constructs, fluency was the one that was the most elusive and contentious – difficult to define, difficult to test, and only rarely achieved by classroom learners.

It’s true that fluency has been defined in many different, sometimes even contradictory ways, and that we are still no nearer to understanding how to measure it, or under what conditions it is optimally realized. See, for example F is for Fluency.

But I’m increasingly coming to the view that, of the two constructs, it is accuracy that is really the more slippery. I’m even wondering if it’s not a concept that has reached its sell-by date, and should be quietly, but forcefully, put down.

Look at these definitions of accuracy, for example:

- “….clear, articulate, grammatically and phonologically correct” (Brown 1994: 254)

- “…getting the language right” (Ur 1991: 103)

- “…the extent to which a learner’s use of the second language conforms to the rules of the language” (Thornbury 2006: 2)

Correct? Right? Conforms to the rules? What could these highly normative criteria possibly mean? Even before English ‘escaped’ from the proprietorial clutches of its native speakers, by whose standards are correctness or rightness or conformity to be judged?

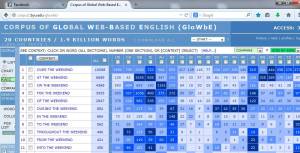

Take my own variety of English for example: I was brought up to say ‘in the weekend’. I found it very odd, therefore, that the coursebooks I was using when I started teaching insisted on ‘at the weekend’. And then, of course, there were all those speakers who preferred ‘on the weekend’. It was only by consulting the Corpus of Global Web-based English (Davies 2013) that I was able to confirm that, in fact, of all the ‘preposition + the weekend’ combos, ‘in the weekend’ is significantly frequent only in New Zealand, while ‘on the weekend’ is preferred in Australia. OK, fine: as teachers we are sensitive to the existence of different varieties. But if a learner says (or writes): ‘In the weekend we had a barby’, do I correct it?Moreover, given the considerable differences between spoken and written grammar, and given the inevitability, even by proficient speakers, of such ‘deviations’ from the norm as false starts, grammatical blends, and other dysfluencies – what are the ‘rules’ by which a speaker’s accuracy should be judged?

In fact, even the distinction between written and spoken seems to have been eroded by online communication. Here, for example, are some extracts from an exchange from an online discussion about a football match. Ignoring typos, which ‘deviations’ from standard English might be attributed to the speaker’s specific variety?

>I don’t care about the goal that wasn’t given; I care about how bad we played particularly when under pressure. Base on the performance from last three games we will be hammered when we play a “proper” decent side!! People think we are lucky to aviod Spain and get Italy but lets not forget the Italian draw Spain so they are no pushovers.

> yes we was lucky, but all teams get lucky sometimes. thats football, you cant plan a tactic for good or bad luck.

> Devic was unlucky to not have the goal allowed and the official on the line needs to get himself down to specsavers but as Devic was offside the goal should not of counted anyway. Anyway I pretty fed up with all the in fighting on here so I am not bothering to much with these blogs for the foreseeable future.

> also on sunday night i will be having an italian pizza i think it will suit the mood quite nicely

I think that the point is here that nit-picking about ‘should not of’ and ‘base on’ is irrelevant. More interestingly, it’s virtually impossible to tell if the deviations from the norm (e.g. ‘the Italian draw Spain’;’ we was lucky’; ‘I pretty fed up’…) owe to a regional or social variety, or to a non-native one. The fact is, that, in the context, these differences are immaterial, and the speakers’ choices are entirely appropriate, hence assessments of accuracy seem unwarranted, even patrician.

Unless, of course, those assessments are made by the speakers themselves. Which one does. Following the last comment, one of the commenters turns on the writer (who calls himself Titus), and complains:

>Titus. Please, please, please go back to school. Have you never heard of punctuation? What about capital letters? How about a dictionary? Sentences? Grammar?

It’s as if Titus is being excluded from membership of the ‘club’, his non-standard English being the pretext. To which Titus responds, with some justification:

> didnt know this was an english class? i am very intelligent and do not need to perform like its a spelling b on here

Which is tantamount to saying: accuracy has to be judged in terms of its appropriacy in context.

All of this has compelled me to revise my definition of accuracy accordingly. Here’s an attempt:

Accuracy is the extent to which a speaker/writer’s lexical and grammatical choices are unremarkable according to the norms of the (immediate) discourse community.

Thanks to corpora, these norms can be more easily identified (as in my ‘in the weekend’). A corpus of ‘football blog comment speak’ would no doubt throw up many instances of ‘we was lucky’ and ‘should of won’. ‘Unremarkable’ captures the probabilistic nature of language usage – that there is no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’, only degrees of departure from the norm. The greater the departure, the more ‘marked’.

The problem is, of course, in defining the discourse community. Consider these two signs, snapped in Japan last week. To which discourse community, if any, is the English part of each sign directed? Assuming a discourse community, and given its membership, are these signs ‘remarkable’? That is to say, are they inaccurate?

References

Brown, H.D. (1994) Teaching by Principles: An interactive approach to language pedagogy. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall Regents.

Davies, M. (2013) Corpus of Global Web-Based English: 1.9 billion words from speakers in 20 countries. Available online at http://corpus.byu.edu/glowbe/.

Thornbury, S. (2006) An A – Z of ELT. Oxford: Macmillan.

Ur, P. (1991) A Course in Language Teaching: Practice and theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hi Scott

Thanks for another thought provoking discussion. I agree the discourse community is important in considerations of language use and what is considered appropriate. However, my experience confirms what you were saying in relation to your example “in the weekend”, which is discourse communities themselves very often disagree about the most appropriate wordings. When I was growing up in South Africa I believe it was ‘on the weekend’.

I wonder if Halliday’s ‘context of situation’ and ‘meaning potential’ might be useful terms as well. This accounts for variation within the discourse community, so different options are considered acceptable based on the meaning the speaker has in mind. In your example then, ‘in’, ‘on’, ‘at’, etc. could all be appropriate as they just ‘mark’ slightly different meanings. But I suspect there must be a limit as far as accuracy goes, as there are some wordings which aren’t suitable to the context, and which don’t satisfy the ‘meaning potential’.

I was thinking about this recently, when I indirectly corrected a student who said “… ate lunch …” with …” had lunch …”. It seemed petty at the time and I was wondering about the benefit of pointing them towards the use of ‘have’ with lunch. But then I thought that as language is an evolved system, there might be value in highlighting the use of ‘have’ in this context, as students could then perhaps be made aware of other uses of ‘have’ showing the patterns, or what Willis called ‘classes of words’, i.e. words which are linked semantically in some way, and seem therefore to share similar patterns. I think this might afford them more opportunities to make generalizations from these instances of language.

As a rule, I don’t usually overtly point to students’ errors, but instead try to highlight alternative wordings which might be more common in more proficient speakers. I find this naturally highlights different options, which allows for a level of variation. But I guess the line between what is ‘acceptable’ or not will always shift as the system adapts.

“This accounts for variation within the discourse community, so different options are considered acceptable based on the meaning the speaker has in mind.” I agree, Grant – but the options are constrained by the norms of the discourse community, unless the speaker wants to flout these for a special effect. The problem for teachers is that we don’t always know what the speaker (i.e. the learner) has in mind, so the default position is conformity to a notional idea of ‘standard English’. But I like your approach to error – not correction so much as ‘well, that’s one way of saying it – this is what I would say [given that situation and that discourse community – and, possibly, your current state of knowledge of the language]’.

That’s the potency of the Hanashi method. the story is the property of the teller, it’s his/her responsibility to convey the thoughts that are the meaning of the story. The receiver never knows what these thoughts are for certain. Scary!

“but the options are constrained by the norms of the discourse community, unless the speaker wants to flout these for a special effect. The problem for teachers is that we don’t always know what the speaker (i.e. the learner) has in mind, so the default position is conformity to a notional idea of ‘standard English’.”

I can certainly see what you are saying Scott and I kind of agree, but hasn’t the ‘discourse community’ come to ‘agree’ on certain wordings which have evolved as the standard. Which doesn’t mean the other wordings are inaccurate, just not standard at this point in time or place. What determines the accuracy is the meaning which emerged from the activity/ context. This may sound banal, but it might be a useful point because as soon as we refer to a ‘discourse community’ it feels like we’re drawing an artificial line between those in and out of the circle. This might be unhelpful as we are all part of different overlapping ‘discourse communities’ at the same time each with their own influences. Which is why English teachers’ rooms are full of (sometimes not so) tongue in cheek discussions revolving around wordings, and perhaps accounts for Titus and his fellow commentator above.

I have found your book ‘Natural Grammar’ useful in this sense as focusing on the possible meanings associated with high frequency words allows for decisions to be made regarding accuracy. So to return to your previous example a student who says, “In the weekends I go to Dubai.” can be considered to have been accurate since one of the meanings associated with the item ‘in’ is a period of time. The meaning potential ‘allows’ for this option amongst others, even if it is not the option I would have chosen. Decisions on accuracy surely need to be made according to wider considerations at the system level, not the individual level. Of course the two levels ‘speak’ to each other so natural evolution of the system will occur anyway according to emerging conditions, and different wordings will come and go.

I think this may be an advantage that corpus linguistics offers us. If we can understand the emerging patterns of language better, we can perhaps make better decisions and find a balance which accounts for Friederike’s concerns regarding adopting “a very liberal stance on accuracy and consequently appropriacy” and the “intolerance to “errors”” which Miguel highlights below.

“…hasn’t the ‘discourse community’ come to ‘agree’ on certain wordings which have evolved as the standard. Which doesn’t mean the other wordings are inaccurate, just not standard at this point in time or place.”

Yes, I agree, Grant, but what we’re really talking about here is ‘idiomaticity’, what Pawley and Syder years ago (1983) called the puzzle of ‘nativelike selection’: the fact that of all the possible ways of saying something, there are only a small set that ‘have evolved as the standard’, as you put it. The learner’s task, according to Pawley and Syder, is to distinguish ‘those usages that are normal or unmarked from those that are unnatural or highly marked’.

In advance of a recent trip I received an email from one of the organizers who had to arrange meals, among other things, and who asked: “Do you have something that you can’t eat?”

Grammatically perfectly accurate, but idiomatically marked. Remarkable, even, when compared to the ‘standard’ ‘Is there anything you don’t eat?’

So, let me suggest we dispense with the notion of accuracy altogether, and replace it with the notion of ‘appropriate idiomaticity’.

hi Scott

there’s a nice (albeit v. small) study using a learner corpus that found that native speakers ratings of proficiency correlated least with accuracy scores of the learners and most with accent and pragmatic ratings – How fluent are advanced German learners of English (perceived to be)? Corpus findings vs. native-speaker perception [http://www.helsinki.fi/varieng/series/volumes/13/gotz/]

the implication is that accuracy is important for beginners but not so for more advanced students

in your example of city signs if an English speaking non-Japanese stepped on the grass and was prosecuted, how the case would proceed would to a large extent depend on whether the suspected offender understood keep off.

so if i was the suspected offender maybe would argue that i am a beginner in English and did not understand the phrasal verb keep off 🙂

ta

mura

Hi Scott and everybody,

Scott, you asked the question “by whose standards are correctness or rightness or conformity to be judged?” and answer it with:

“Accuracy is the extent to which a speaker/writer’s lexical and grammatical choices are unremarkable according to the norms of the (immediate) discourse community.”

What more is there to add? The objective of nearly all the students I’ve ever had was to use the kind of Standard International English we all use on this and similar blogs. (Even those who were keen football fans did not wish to learn the kind of English Titus uses in your quote above.) It’s true there are tiny differences between the members of this community and we sensitive English language nuts notice them, but as the corpus study Mura refers to confirms, most native English speakers don’t: what they notice as “foreign” is the pronunciation.

I don’t understand, Mura, “why the implication is that accuracy is important for beginners but not so for more advanced students”?

By the way, I first interpreted Mura’s lack of capitals at the beginnings of paragraphs as an E. E. Cummings sort of stylistic choice. Then I realised that it was more likely because he was writing on a smartphone. But that says more about my age than Mura’s English.

Cheers,

Glenys

hi Glenys, in the corpus study it was found that the most accurate learner did not get the highest rating of perceived proficiency, hence advanced students who are very accurate may likewise not be rated as very proficient

btw i usually use desktop when posting comments so my non-use of capital is due to laziness (that extra keypress for shift!), phones usually capitalise first letter in sentence automatically

ta

mura

Thanks Mura – yes, the notion of ‘perceptive fluency’ (i.e. the impression one gives of being fluent) seems much more interesting than measurable fluency (e.g. speech rate, number of unfilled pauses etc). I haven’t checked your link yet, but in a recent book (Götz, 2013, Fluency in native and nonnative speech, John Benjamins) a small-scale study of NS non-specialists’ perceptions of fluency found that pragmatics (e.g. realizing questions, responding to questions, being polite etc) was the highest scoring indicator of the subjects’ fluency. Accuracy was up there too, but the NS non-specialists were hopeless at assessing it: ‘The learner with the least number of errors gets the lowest ratings for perceived accuracy’. It seems that it is mianly only teachers who can recognize accuracy when they see it, and who (mostly) prioritize it.

Scott,

If a student wrote “In the weekend we had a barby,” I’d correct their spelling of barbie. Or is that how it’s spelled in NZ? 🙂

On another note, do you think native speakers actually make “errors” when speaking? Slips of the tongue, yes, but errors? Of course many will argue that, “If I’d have known he was coming…” is wrong but if the speakers own the language, do we ever get it wrong? Perhaps misunderstood.

Scott C.

“…do you think native speakers actually make “errors” when speaking?” Not really. They violate the rules of prescriptive grammar (‘a huge amount of people’, ‘he plays like Rafa does’ etc) but these can’t really be counted as ‘remarkable’.

It’s interesting that we use the term ‘fluency’ for both NSs and NNSs, but ‘accuracy’ only for NNSs. For NSs we tend to say – not that X’s speech is inaccurate – but that it is not ‘proper’ or ‘good’ English.

It is slippery isn’t it? And I’m also now wondering about ‘errors’, or maybe modifications in our self-created criteria of accuracy (going by Glenys and Scott C’s comments – “Accuracy is the extent to which a speaker/writer’s lexical and grammatical choices are unremarkable according to the norms of the (immediate) discourse community.” and “but if the speakers own the language, do we ever get it wrong? Perhaps misunderstood.”)

Particularly, are there times that someone who can speak English perfectly well, following ‘standard English’ rules, actually changes to fit in with another discourse community? Could a football fan change their language depending on whether they are at home with their family compared to when they’re at that game?

On another note, I’ve never come across ‘in the weekend’ (maybe don’t meet that many NZ English speakers), but I really don’t like ‘on the weekend’!

‘I’ve never come across … and I really don’t like …’

Mike, I think you’ve put your finger on both the experiential and the affective factors that make departures from the norm ‘remarkable’. If you haven’t ever heard someone say ‘I’m loving it’, for example, it will trigger a negative reaction. Likewise, if you value the distinction between ‘few’ and ‘less’ (because you think it adds clarity to the language, or simply because it indexes you as educated) you will be offended or aggrieved by ‘Ten items or less’ signs in supermarkets. I suspect most of our learners have neither the experience nor the culturally-induced attitudes to detect ‘remarkableness’ of this type. They simply want to get on with the job of being maximally communicative.

Swings and roundabouts.

When I started teaching English was mainly a classroom activity and we teachers had the final word on what was considered grammatically correct. Incidentally I had to spend a lot more time on pronunciation work than I do now. Now – at the latest with the advent of the internet, the language belongs to everybody, fluency has been absorbed with the ubiquity of the language and we teachers (me at least) gallop alongside our students to keep up with the new structures and usages being bandied about.

Misunderstandings will occur whenever people get together, and ironing them out intensifies their experience with the language.

I only see problems when students have to adopt a particular style of English to take tests written by English teachers.

Thanks Helen for reminding us that ‘misunderstandings will always occur’ and hence that the pedant’s argument that grammatical accuracy reduces misunderstandign is a specious one. Perhaps we should be training our learners – not to be accurate – but to recognize, repair and negotiate misunderstanding?

Well a bit of both, surely. You need the accuracy to “recognize, repair and negotiate misunderstanding”, but accuracy alone is in every sense an academic (i.e. clever, but not necessarily useful) quality.

As a non-native speaker teacher educator I have a slightly different stance on accuracy. Native speakers tend to know which register and level of lexical and grammatical accuracy to adopt in which setting. They have a number of options. And I don’t believe that online discussions about football with peers can be seen to be of the same quality as emails to other staff members or customers. Are we really doing learners a service if we adopt a very liberal stance on accuracy and consequently appropriacy? I don’t know which proportion of learners of English worldwide would only ever use the language in informal settings. Those that need English in their jobs would probably be happy to be taught a “safe” standard variety which does not result in raised eyebrows. Being less formal and “accurate” will follow surely when they interact with others and encounter more and different expressions in English.

Thanks for your comment, Friederike. I appreciate and welcome your particular vantage point on this discussion. Many non-native speakers feel that their accuracy (whether of grammar, idiom or accent) has been hard won, and should not be belittled or otherwise compromised. But I’m not suggesting that online discussions about football should serve as a new ‘standard’. I’m simply saying that accuracy can be assessed only in relation to the context of use – and that those best placed to assess it are those familiar with – and invested in – this context. Those that need English for their jobs (as you say) or for academic study will be expected to conform to the norms of precisely those professional or academic contexts – which – for want of a better benchmark – probably is the ‘standard’ adopted by current textbooks, reference grammars etc. But those who do not aspire to these contexts and uses might be wasting a lot of time trying to master a variety that may well be inappropriate.

Hi Scott. I am also a non-native teacher. My first language is Spanish and we have a language regulator called “Real Academia de la Lengua Española” which prescribes language. If Bartosz used the word “escuchante” in Latin America, he would be prompted to use “oyente” or “radio escucha”. Let’s not get into detail. So, at least in Mexico, an inaccurate native speaker (in whatever context) is seen by many as being ignorant and may result in the person being the object of ridicule. This is a challenge, because as you mentioned, we can’t impose a one-size-fits-all target of accuracy in English as it could be done in Spanish. So, in the end, many teachers end up teaching English as they learned Spanish. In your example, Titus replies to one of the commenters with a great point. But your example shows that intolerance to “errors” exist. In my experience as a user of English as a second language, I have been the victim of racism many times because of my accent and fewer times because of my “correctness”. I felt really bad for a long time and I thought I had wasted so much time and effort in studying English. How would you prevent a learner from feeling discouraged if he is judged?

Thanks for the comment, Miguel. It’s true, there’s no denying the stigma that is often attached to ‘sounding foreign’. I suspect that, sadly, we are hard-wired to mistrust strangers, hence our hypersensitivity to even the subtlest differences in accent. Nevertheless, more than half the world’s people live in a place in which they were not born (I invented that figure – but you get the point) and hence there is much more inter-lingual contact than ever, which can only serve to break down prejudice and make the remarkable unremarkable.

In a recent book (Language & Mobility 2012) Alistair Pennycook explores the notion of ‘passing’ (as in ‘to pass as a native speaker’), and he construes it as being able to ‘perform like a local’: ‘Performing like a local is not about achieving a level of phonological or syntactic accuracy as measured by some external criteria (proficient), nor just getting by (passable), nor being acknowledged by dint of prior social status (legitimate) but rather is a question of one’s language use being perceived to work …. Being a resourceful speaker is what we are surely aiming at. By this I mean both having available language resources and being good at shifting between styles, discourses and genres. … We do not pass as a native speaker of some imaginary thing called a language; if we pass as anything, it is always in a particular context, in a particular genre, style, discourse or practice’.

A classic instance of ‘passing’ is ‘Wes’, the Japanese immigrant to Hawaii who was the subject of a longitudinal study by Richard Schmidt. ‘Wes’ was accepted as a legitimate speaker by the community he worked with in Hawaii, despite having a ‘low level’ of accuracy. He partly achieved this by ‘willing’ his interlocutors to understand him. Schmidt writes, “Why do people think his English is so good when he doesn’t use prepositions, articles, plurals, and tense? I think it’s because when people talk to him and listen to him, they don’t notice that he doesn’t use them.” (cited in Bergsleithner, J., Frota, S., & Yoshioka, J.K. eds. Noticing & Second Language Acquisition: Studies in honor of Dick Schmidt, Manoa: University of Hawai’i Press.)

Significantly, the only group that rated Wes’s English poorly were …. English teachers!

on a ligher note:

Miguel, you should come to Poland and try to learn Polish. We LOVE foreigners who try to speak Polish and we LOVE their mistakes. I guess Poles just assume that Polish is too difficult for most foreigners to learn.

Those foreigners who become quite fluent in Polish are likely to win our heart and become TV celebrities! Let me give you some examples.

One of the judges on Masterchef Poland grew up in France (his family had emigrated from Spain if I remember correctly). He’s famous for his mistakes.

Then, the host of another reality show is of Polish origin, but she moved to the US when she was a little girl. She has a foreign accent, uses a lot of English expressions and makes plenty of mistakes.

Between 2003 and 2008, there was a programme called “Europe is likeable” (or “Europe can be liked”). The host of the show invited foreigners who lived in Poland and spoke (some) Polish to talk about different apects of life in their countries. The programme was a spectacular success.

Disclaimer: This is not true if you’re a native speaker of Russian, Ukrainian or other Slavic languages.

Scott, thank you so much for your answer. Let me share this short article I found http://www.futurity.org/why-we-distrust-foreign-accents/ It might explain why some Americans wanted to speak with someone who spoke “American”. On the other hand, I will gladly read that book. I think that not only “scenarios” change the perception of the speaker’s language working or not but also the listener’s culture. I think it would also be interesting to know how Wes managed to want his interlocutors to understand him and leave a good impression in the end.

Bartosz, I’ve heard Polish women are beautiful and Polish language has a reputation of being extremely difficult. So, it might be worth making myself the object of your laughter. In Mexico, we wouldn’t mistreat a foreigner making a mistake. On the contrary, we love helping them. We are just mean with the locals, weird, huh?

Hi Scott,

Thank you very much for tackling the crucial issue of accuracy. Out of my experience in teaching written expression, accuracy cannot be disregarded as a main aspect in evaluating the students’ production, whether in terms of sentence structure (writing accurate sentences which are free of sentence problems), spelling (writing words accurately), accurate punctuation, etc. So, accuracy of writing mechanics plays a big role in the overall evaluation process. What’s more, even when the ideas expressed are creative and original, the lack of accuracy distorts the whole shape of the written piece and affects the evaluation scheme.

I think that “accuracy” is entwined with “rules”. Language is a system of structures that function according to a set of rules lexically, grammatically, phonologically and phonetically. So, accuracy stems from the appropriate use of the rules that govern the language. Grammatical accuracy is dominant over other language aspects I think, because of the prominence of grammar rules (I think language learners tend to link the word “rules” to grammar mostly often).

Taking into consideration that language is used for communication, accuracy in speaking does not seem to be as important as in writing because the fact that the message is being conveyed, and providing immediate feedback to correct pronunciation mistakes can influence the “fluency” of the speaker, are example factors that reduces the focus on accuracy.

In the literature, other terms like “appropriateness” and “correctness” along “accuracy” are also mentioned when discussing grammar, and it is difficult to draw a distinction among them.

Very grateful for the post Scott,

Manar

Manar, you say that ‘“accuracy” is entwined with “rules”’. Well, yes, that’s certainly how teachers and students have traditionally viewed it. I’m suggesting, on the other hand, that it is ‘entwined’ with appropriacy – that you cannot assess accuracy in the absence of knowledge of what speakers in that context actually do. So, not rules, but norms.

Scott, isn’t Titus only choosing (correctly) the register he needs to take part in the discussion? Presumably, if he met the queen tomorrow, he would speak in a different way. Of the two photos, I would say that only the second was accurate – the first could almost be used as a ‘wet paint’ sign!

Yes, Andrew, Titus is indeed choosing the appropriate register – that was my point, and it was mean-spirited of the other commenter to condemn him for violating the norms of a completely different register.

In short, it seems to me to be impossible to extricate the notion of accuracy from the notion of register.

The two go hand in hand, like fish’n’chips, down the holy aisle of language capamabilities.

Hi Mike,

I forgot that there were two Scotts here. “Accuracy is the extent to which a speaker/writer’s lexical and grammatical choices are unremarkable according to the norms of the (immediate) discourse community” is a quote from Scott T. not from Scott C.

No dialect, including Standard International English, is static. The users are changing it all the time – that’s the way languages function. Otherwise we Westerners – English speakers and others (I think you know who I mean, even if some of us, or our parents, have emigrated elsewhere) would still be speaking Proto Indo-European. There is a constant tension between the natural tendance of any language to change and the practical need to prevent a lingua franca from splitting into mutually unintelligible dialects. A lingua franca is useful – but a language becomes a lingua franca not because it is linguistically superior or more resistant to change, but for historical and political reasons.

—-

The Grammar Geeks Group on Linkedin has had many discussions about the difference between prescriptive grammar rules imposed by an authority: the teacher, coursebooks, style manuals… and descriptive grammar rules which describe the regularities of any language/dialect at a particular moment in time. Many people, including teachers, are not clear about the distinction. A lot of the discussion about grammatical rules is conducted in emotive, judgemental terms and suggest that people who speak anything other than the Standard are somehow inferior as people.

Cheers,

Glenys

Thanks Glenys. I’m struggling a bit with the prescriptive-descriptive distinction, from a theoretical perspective at least. When you take a description (of ‘any language / dialect at a particular moment in time’, as you put it) and make it the basis of both your syllabus and your criteria for assessing accuracy – and, hence, for testing – aren’t you in a sense prescribing that description? I’m not suggesting that ‘anything goes’ – only that we shouldn’t be too complacent about the way we use so-called descriptive grammars.

In a discussion like this I like to think I’m a descriptivist, but in the classroom I was a prescriptivist. I don’t really see how it’s possible for EFL or ESL teachers to be otherwise. I did not accept the sort of sentences my students sometimes came up with “Do I can go toilets, My Teacher?” Does any teacher? But a self-aware prescriptivist is quite different from one who believes that there is something inherently “bad” in saying, for example, “Less people play tiddlywinks than football”.

I recently experienced an example of how rapidly language can evolve. My nephew came to visit me here in France: his mother’s Japanese and he was brought up in Japan. He’s quite fluent in English, maybe B1, but makes lots of “mistakes” judged by the norm of International Standard English. We just chatted – I wasn’t in my teacher role. In just a week, I noticed how much my English was moving towards his. If we’d been isolated on a desert island, I’m pretty sure that within 10 years we’d have been speaking a new dialect of of English. I realised too that I didn’t change my accent – no “l” for “r” – and also that it was the only aspect of his English I corrected him on. Just an anecdote but in agreement with the corpus based study Mura drew our attention to.

If English speakers (native and non-native) in their local groups all over the globe went down road my nephew and I were going, there’d soon be no Standard International English and we’d have no lingua franca (at least, not one based on English) which enables people from diverse backgrounds to participate in a discussion such as this one. Such a Standard is useful and practical – not that that we have to use it all the time.

Hi Glenys,

Thanks for clarification – so I was quoting you quoting Scott T, and also quoting Scott C!

I quite like your revised definition of accuracy, Scott.

It seems to me to be a more precise (scholarly?) expression of Penny Ur’s idea. She mentions “getting the language right”. I’ll assume that “right” doesn’t always mean “(prescriptively) correct” for her.

I think it’s important to add that users don’t depart from the “norm” just because they don’t know it. They may have reasons to do so on purpose (e.g. in advertising campaigns).

It’d be good to give the same privilege to non-native speakers too! 🙂

I’m a pretty proficient speaker of Spanish as a foreign language, so here’s an example in Spanish:

If you listen to something (e.g. a radio programme), you are an ‘oyente’ in Spanish. It comes from the verb ‘oír’ (to hear) and it’s the only word for ‘listener’ that is accepted by the Spanish Language Academy (which means it’s included in its Dictionary).

Still, some Spaniards and I prefer to use an alternative form (‘escuchante’) to talk about radio programmes that we really like. ‘Escuchante’ comes from ‘escuchar’ (to listen) and it seems to describe actions rather than states/perceptions (hearers vs listeners). The problem is that it’s not an official word in Spanish. You won’t find it in THE Dictionary of Spanish.

Although I have been corrected a couple of times by hard-line prescriptivists, I’ll keep using the illegal ‘escuchante’: not because I’m stupid too learn the rules, but because that’s exactly the word that I need to talk about my favourite radio programmes.

They were not hard-liners. Your wordsmith game breaks communication down. No native speaker of Spanish would interpret ‘Soy un escuchante’ as ‘I’m a radio listener’. It is quite a ‘remarkable’ lexical choice within the Spanish-speaking discourse community at large (according to Scott’s view on accuracy.)

J.J. Almagro, let me start with a simple question:

Is your claim that “No native speaker of Spanish would interpret…” EVIDENCE-based? If you have made it because you’re a native speaker of Spanish, then, sorry, I’m not really convinced by your OPINION.

Google “escuchante de radio” and you’ll see it’s been used by some native speakers. I’m not the one who invented the word.

Some facts about the word:

Here’s a short text explaining why ‘escuchante’ is not in the Dictionary now despite being a well-formed word:

http://www.fundeu.es/consulta/escuchante-763/

Also the RAE has confirmed recently that ‘escuchante’ is a well-formed word: https://twitter.com/RAEinforma/status/311085114891313152

About the Spanish-discourse community:

I admit that ‘escuchante’ might be a ‘marked’ choice for SOME speakers of Spanish, since there is a more frequently used alternative term. But that’s exactly my point: I want a ‘marked’ word to express myself precisely, i.e. by contrasting ‘oyente’ and ‘escuchante’. I haven’t got rid of ‘oyente’ completely. I simply need both words.

Finally, I don’t agree it causes communication breakdown. The meaning of ‘escuchante’ is quite transparent: it can be reconstructed if you know ‘eschuchar’ + -nte suffix (even if you don’t like the form). That’s something that every native speaker (and most intermediate learners) should be able to do.

Hi, Bartosz.

Yes, I’m a native speaker of Spanish.

I wouldn’t say that the markedness of your ‘escuchante’ is just an opinion. It’s a ‘lexicality’ judgment based on 48 years of exposure to and use of the language.

I am very much aware of the importance of language play in SLA. Totally agree. I’m also a literary translator, which has allowed me to toy with metaphorical constructs (equivalences and marginalities), and creative word choice, word building, and word combinations.

Do you know what my first word association with ‘escuchante’ was? A student on an audit basis. A marginal one? A Native-American with an ear on the ground.

No transparent at all.

How would notions like ‘identity’, ‘idiolect’ and ‘creativity’ factor in the definition of accuracy? These notions that may characterize L2 learners’ ZPD, this third space…

Indeed, idiolect (one’s own speech style) and creativity also challenge the notion of accuracy – and also my own defintiion of it. Poetry is, almost by definition, ‘remarkable’ – but perhaps only outside the community that reads it. The problem is that, as Luke Prodromou among others has argued, when learners attempt to be creative with the second language (as in Bartosz’s ‘escuchante’) they are corrected. When native speakers do it, they are not corrected – they are even congratulated on their ingenuity. Double standards?

I guess native speakers of any language ‘know’ when departures from unmarked forms are necessary creative ímpetuses, or spontaneous attempts to lexicalize the unnecessary.

By the way, these three lines were far from spontaneous…

Look, it’s quite simple. We need a Ministry of Correct English who pronounce on matters of accuracy. This weekend business is easy, it’s “at the weekend” or “during” is permissible. Other colonial variants are incorrect and that’s that.

Confusions such as the use of the word alternate when the correct word is alternative will be corrected, no longer will people “protest the injustice” when they actually want to protest “against” the injustice and the heinous “train station” when we all know that the correct term is “railway station” will no longer be an issue. Anyone who uses an adjective rather than an adverb will probably be shot at dawn.

All BBC, Civil Service personel and public employees will only be able to stay in post if they demonstrate a level of accuracy acceptable to the MOCR.

I would of thought it was all self evident!

I really hope you’re joking with your use of ‘would of’ there, Peter 😉

Of course if there ever was something like a Ministry of Correct English a lot of people would just rebel against it by using non-standard forms even more.

Pompous prescriptivists always set themselves up for ridicule.

My two cents on Scott’s post is that it seems to be going way too far to scrap the concept of accuracy altogether. The revised definition given in the article fits the description of accuracy which Scott lays out very well.

Hi Scott,

Great post! And it got me thinking about your definition. I’m just back from a run and on my way back stopped to talk to Fran, an ex-student of mine. I’ve been living and working in Spain for 25 years now and as would be expected have reached a fairly decent level of “accuracy” and “fluency”, have read quite a few Spanish classics, read the newspaper and converse on a wide variety of subjects on a daily basis. So why do quite a few people speak to me as if I were brain damaged? The quick answer is my horrible accent and intonation. When you have a Belfast accent speaking Spanish people automatically assume that you understand as you sound, rather than how “accurately or fluently” you speak.

Do I suffer from the same prejudice with my students? I have to admit I do. A few months ago I carried out a level test for a student who spoke with a wonderful London accent. With that accent I automatically assumed that her grammar and vocabulary would be up to the same standard. It took me a while to realise that I’d made a mistake. What she said was pretty dire compared to how she said it. (Incidentally she fooled the FCE examiners too and passed the oral exam).

The point I’m making is that any definition of accuracy which focuses solely on lexical and grammatical choices without taking phonology into consideration would only be useful for written rather than spoken English. Or have I totally misunderstood the definition?

Fantastic post, Scott. As you say, “The problem is… in defining the discourse community.” At one company I teach at I used to correct the students’ pronunciation of the word “inVENtory” until I sat in on a conference call and realized that all the L1 Spanish, Italian and French speakers who were at the other end of the call said it exactly the same way. Their particular corporate subset of international business English had settled on this pronunciation as correct and there is little I could do to change it if I wanted to (and now I don’t). As you suggest, there is a vast array of discourse communities and even my “standard English” might be wholly inappropiate–and therefore judged as non-fluent–in a number of them.

Thanks for the comment – and for bringing pronunciation into the equation. I deliberately left it out of my definition (I referred to “lexical and grammatical choices” where I could have been more inclusive, e.g. “linguistic choices”) because (a) you’ll never get rid of an L1 accent, even if you wanted to, so to fold it into a general notion of accuracy would seem to weight the dice against the learner ever being judged fairly – your student with the London accent is a sort of coutner example!; (b) unlike ‘holes’ in your grammatical or lexical knowledge, which you can skirt around using communication strategies, you can never ‘disguise’ your L1 accent – so pronunciation does seem to be a ‘special case’; and (c) there are huge variations in accent among NSs – even more, arguably, than in grammar and lexis – so how do you identify the norm from which the learner is departing or to which the learner should aspire?

Nevertheless, I think you are absolutely right if you mean that the criteria of remarkableness (rather than, say, native-like-ness) should apply to pronunciation, alongside – but not to be confused with – intelligibility.

Thanks a million Scott.

That certainly puts things in a new perspective. This concept of “remarkableness” (do you mean worth remarking on / interrupting for / commenting on / correcting?) seems to point us more in the direction of a pragmatic approach to teaching, the central goal being to move students forward rather than an obsessive fixation on accuracy, which turns out in the end to be a highly subjective and arbitrary construct, often becoming a hindrance instead of a yard stick for progress. Does that encapsulate your central point or am I way off the mark?

By ‘remarkableness’ I wanted to capture the sense of the technical term ‘markedness’, a ‘marked’ form being one that is less typical, less basic, less frequent, more complex, more salient than an unmarked one. I also wanted to capture the idea that your attention is temporarily distracted by such departures from the norm: you notice them. This might lead you to the conclusion that the speaker is ‘foreign’, a learner, or otherwise not one of your own speech community, which in turn might induce certain responses: ‘foreigner talk’, extra effort, or even avoidance.

Hi Scott,

Most of the examples of inaccuracies so far have been of the “ate/had lunch” / “on/in the weekend” type, haven’t they, by which I mean local mistakes (for lack of a better term and “local” in the discourse, rather than geographical sense).

I’m not in principle opposed to a sensible slackening of the reins with which ELT’s grammar police get to determine what’s right or not, but I do wonder how a such a change should be communicated to teachers worldwide. Surely we don’t want teachers to view most developmental mistakes (which with a little scaffolding + feedback + renoticing can bring students closer to the target forms) as an acceptable final product. I think what I’m trying to suggest is that “I no went there yesterday”/”Do I can ask a question?” and “in/on the weekend” shouldn’t be considered in the same terms or else the notion of interlanguage and interlanguage restructuring will have very limited use in ELT pedagogy.

There’s also the issue of ultimate level of achievement, which you mentioned above. As a non-native speaker, I am constantly being assessed on my language proficiency, both formally and informally (e.g.: If I send an e-mail to my editor at 3am, forget to proofread it and let a typo or two slip in, chances are that she will wonder whether those are simply typos). So accuracy – as it is defined by mainstream ELT – matters a lot to me. And it probably matters a lot of to most non-native teachers, who, as you said, fought very hard for their accuracy and depend on it to keep their jobs and advance in their careers. And it’s precisely these people that will have to buy the idea that, at the end of the day, had lunch and ate lunch are both fine.

Thanks, Luiz. – always measured and insightful!

But let me dispel the idea that I am talking about a ‘slackening of the reins’. I’m sorry if I gave that impression. What I am saying is that you can’t impose a one-size-fits-all target of accuracy on all learners. If you like, I am substituting the notion of accuracy with one of ‘rightness’ – not as ‘correctness’, but in the sense of ‘fitness for purpose’. As Diane Larsen-Freeman puts it, while teachers need to understand the natural processs of interlanguage development (and hence accept the inevitability of “error”) they ‘are [also] responsible for aiding learners to at least approach the norms of the community in which the learners seek membership’ (2013: 214). If the community in which the learners seek membership is that of English language teachers, then, of course, the bar will be raised very high.

Of course, the problem is that we don’t often know (because they don’t) what the community is in which the learners seek membership, so we teach them (and assess them) as if they were ALL going to be teachers of English or rocket scientists or whatever.

As an instance, the assessors manual for Cambridge Proficiency once included a Q&A section. One of the questions went something like: ‘Is colloquial language or slang permitted [in the exam]?’ And the A: Yes, so long as it’s grammatically correct.

Larsen-Freeman suggests that, instead of setting some kind of idealized ‘end state’ as the putative objective of teaching, we should set the goal ‘as developing capacity’, where ‘capacity is that which enables learners to move beyond speech formulas in order to innovate’. And she adds, ‘Within this overall goal, identify particular contexts of use, contexts in which norms for local “success” can be established’ (op. cit).

‘Local success’ would seem to be a more realistic goal than some kind of global ‘gold standard’.

Larsen-Freeman, D. 2013. ‘Another step to be taken: Re-thinking the end point of the interlanguage continuum’, in Han and Tarone (eds.) Interlanguage:Fortty years later. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

The one thing that strikes me, Scott, when I look back over the years, is that what we were sold back in the early days, the idea of accuracy leading to fluency, was the cart before the horse. Looking back over my own language learning experiences, it’s now pretty obvious to me that first I was fluent – albeit with a hundred and one ‘inaccuracies’ in everything I uttered – and then I became accurate. So it’s great to see you raising question marks against early, narrow definitions of accuracy, and offering us a view that is more fitting to the 21st-century reality of language use in general, and of the reality of a fully globalised English in particlar, and the only thing I’d venture to add is the need to put the horse back in front of the cart.

Yes, Robin, exactly. I don’t know who it was (maybe Stephen Krashen) who pointed out that accuracy (if such a construct exists) is ‘late acquired’, both in first and in second language acquisition. We achieve fluency which we then fine-tune for accuracy. Of course, there’s always the risk that – in SLA – the speaker will dispense with the fine-tuning, a state that used to be called fossilization. All things being equal, I’d rather be ‘fluent but fossilized’ than ‘accurate but non-communicative’.

Scott, I’ve been thinking about “the norms of the (immediate) discourse community” in different places and Gibraltar came to my mind.

Gibraltar is famous of code-switching (English is more prestigious than Spanish), but in fact it’s common to hear people mixing English and Spanish words, syntax and pronunciation in one sentence.

It seems that most native speakers willing to go to Gibraltar should learn some Spanish if they want to pass as a Gibraltarian. Some of their lexical and grammatical choices would probably be ‘remarkable’ if they spoke just “standard” English.

(In fact, they would probably find it difficult to communicate with the local community in some less formal contexts without some knowledge of Spanish.)

Hello Scott,

I’d like to say a couple of words and join the discussion, if it’s not too late.

Once while discussing the overall goal of teaching pronunciation in the EFL context with my trainees (btw using, Scott, your book “About Language”), one young woman very strongly advocated aiding students to go beyond the limits of intelligibility, towards more native-like proficiency (whatever that accent could be). Her main argument was that her own struggle to sound like her listener was embedded in her desire to show respect for her listener, so that her speech could sound easier to process and comprehend, yet with no intention to assimilate or “seek membership” in the target language community. From this perspective accuracy could be defined as the speaker’s willingness to abide by the linguistic culture (language norms as you say) of their listener in order to hold a dialogue (in Bakhtin’s sense). The speaker’s initial idea of accuracy will certainly always depend on their previous experience — what they have been told, taught, exposed to or what they have just picked up.

“Foreigner” talk, that we all can do on instinct, is an adaptive strategy, its intention being to sound more comprehensible. In my opinion, with so many Englishes in the world this strategy should be explicitly trained in the classroom, i.e. students should be made aware of different ways English may sound and how they can notice it and adapt to their potential listener. I would really appreciate it if coursebook writers could kindly include a note about each sample of written and oral texts they use and say where it comes from, where the speaker is from and what features this English variety has.

Hope it was accurate enough to make sense.

Btw, when is the new edition of “About language” due?

Hi scot!

That was surely a very interesting point you made.

But as an efl teacher I would like to understand how does this relate to my teaching? Does this mean that one doesn’t have to put a great emphasis on accurate English, teaching grammar or correct mistakes in writing assignments?

Basically what is my main target in teaching English?

Thanks a lot and a happy new year!

Meshulam Hewitt

Israel

Just another small question.

In your personal opinion, do you think it is good to teach English using modern songs which have incorrect language? To emphasize the differences between spoken language and formal one.

Thanks!

Meshulam

The best you can due for learners is to equip the to explore a language for themselves to find ways of communicating that best suits their own purpose.

Edit: to equip them…..

Hi Scott,

Thank you for sharing your insights on accuracy, I found them very engaging and thought provoking. The fact that Titus says “Didn’t know this was an English class,” strikes me as quite disturbing. Are we English teachers that bad? Always correcting our students and requiring that they speak accurately?

The real question is, like you said, where do we set the boundaries between accuracy and fluency? I strongly believe that educators need to give their students the choice and ability to speak accurately so they can use language in a variety of conditions and situations. Language learners that can only speak their acquired language in certain settings might become fixed on that setting only and won’t be able to expand their knowledge and thought beyond it. However, I do agree with Titus that the language one uses shouldn’t be an indicator of his or her intelligence. Sadly we live in a very biased world, in which language is a means of stereotyping people and placing them in a certain social status. I hope that one day people will have the ability to set aside their prejudiced thoughts and get over the idea that the language one uses is a gauge of how much they know.