(Or: How soon will translation apps make us all redundant?)

An applied linguist collecting data

In a book published on the first day of the new millennium, futurologist Ray Kurzweil (2000) predicted that spoken language translation would be common by the year 2019 and that computers would reach human levels of translation by 2029. It would seem that we are well on track. Maybe even a few years ahead.

Google Translate, for example, was launched in 2006, and now supports over 100 languages, although, since it draws on an enormous corpus of already translated texts, it is more reliable with ‘big’ languages, such as English, Spanish, and French.

A fair amount of scorn has been heaped on Google Translate but, in the languages I mostly deal with, I have always found it fairly accurate. Here for example is the first paragraph of this blog translated into Spanish and then back again:

En un libro publicado el primer día del nuevo milenio, el futurólogo Ray Kurzweil (2000) predijo que la traducción hablada sería común para el año 2019 y que las computadoras llegarían a niveles humanos de traducción para 2029. Parecería que estamos bien en el camino. Tal vez incluso unos años por delante.

In a book published on the first day of the new millennium, futurist Ray Kurzweil (2000) predicted that the spoken translation would be common for 2019 and that computers would reach human translation levels by 2029. It would seem we are well on the road. Maybe even a few years ahead.

Initially text-to-text based, Google Translate has more recently been experimenting with a ‘conversation mode’, i.e. speech-to-speech translation, the ultimate goal of machine translation – and memorably foreshadowed by the ‘Babel fish’ of Douglas Adams (1995): ‘If you stick a Babel fish in your ear you can instantly understand anything said to you in any form of language.’

The boffins at Microsoft and Skype have been beavering away towards the same goal: to produce a reliable speech-to-speech translator in a wide range of languages. For a road test of Skype’s English-Mandarin product, see here: https://qz.com/526019/how-good-is-skypes-instant-translation-we-put-it-to-the-chinese-stress-test/

The verdict (two years ago) was less than impressive, but the reviewers concede that Skype Translator will ‘only get better’ – a view echoed by The Economist last month:

Translation software will go on getting better. Not only will engineers keep tweaking their statistical models and neural networks, but users themselves will make improvements to their own systems.

Mention of statistical models and neural networks reminds us that machine translation has evolved through at least three key stages since its inception in the 1960s. First was the ‘slot-filling stage’, whereby individual words were translated and plugged into syntactic structures selected from a built-in grammar. This less-than-successful model was eventually supplanted by statistical models, dependent on enormous data-bases of already translated text, which were rapidly scanned using algorithms that sought out the best possible phrase-length fit for a given word. Statistical Machine Translation (SMT) was the model on which Google Translate was initially based. It has been successful up to a point, but – since it handles only short sequences of words at a time – it tends to be less reliable dealing with longer stretches of text.

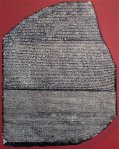

An early translation app

More recently still, so-called neural machine translation (NMT), modelled on neural networks, attempts to replicate mental processes of text interpretation and production. As Microsoft describes it, NMT works in two stages:

- A first stage models the word that needs to be translated based on the context of this word (and its possible translations) within the full sentence, whether the sentence is 5 words or 20 words long.

- A second stage then translates this word model (not the word itself but the model the neural network has built of it), within the context of the sentence, into the other language.

Because NMT systems learn on the job and have a predictive capability, they are able to make good guesses as to when to start translating and when to wait for more input, and thereby reduce the lag between input and output. Combined with developments in voice recognition software, NMT provides the nearest thing so far to simultaneous speech-to-speech translation, and has generated a flurry of new apps. See for example:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZAHfevDUMK4

https://www.cnet.com/news/this-in-ear-translator-will-hit-eardrums-next-month-lingmo/

One caveat to balance against the often rapturous claims made by their promoters is that many of these apps are trialled using fairly routine exchanges of the type Do you know a good sushi restaurant near here? They need to be able to prove their worth in a much wider variety of registers, both formal and informal. Nevertheless, Kurzweil’s prediction that speech-to-speech translation will be commonplace in two years’ time looks closer to being realized. What, I wonder, will it do to the language teaching industry?

As a footnote, is it not significant that developments in machine translation seem to have mirrored developments in language acquisition theory in general, and specifically the shift from a focus primarily on syntactic processing to one that favours exemplar-based learning? Viewed from this perspective, acquisition – and translation – is less the activation of a pre-specified grammar, and more the cumulative effect of exposure to masses of data and the probabilistic abstraction of the regularities therein. Perhaps the reason that a child – or a good translator – never produces sentences of the order of Is the man who tall is in the room? or John seems to the men to like each other (Chomsky 2007) is not because these sentences violate structure-dependent rules, but because the child/translator has never encountered instances of anything like them.

References

Adams, D. (1995) The hitchhiker’s guide to the galaxy. London: Heinemann.

Chomsky, N. (2007) On Language. New York: The New Press.

Kurzweil, R. (2000) The Age of Spiritual Machines: When Computers Exceed Human Intelligence. Penguin.

Recent comments