In preparing the new edition of An A-Z of ELT, I had a slight altercation with my (wonderful) editor, who – on the basis of readers’ reports – queried my claim (in the first edition) that substitution tables ‘have fallen out of fashion’. She felt that, if anything, they were coming back into fashion, citing examples in a number of coursebooks. I disagreed.

In preparing the new edition of An A-Z of ELT, I had a slight altercation with my (wonderful) editor, who – on the basis of readers’ reports – queried my claim (in the first edition) that substitution tables ‘have fallen out of fashion’. She felt that, if anything, they were coming back into fashion, citing examples in a number of coursebooks. I disagreed.

Before I describe how we resolved this argument, a little bit of history.

The use of substitution tables to display the interchangeable items of a grammar pattern have, according to Kelly (1969), been around since the early 1500’s. Here’s an example from a French course of 1534. But, of course, they really came into their own with the advent of structuralism – the view that language (and not just language, but any cultural artefact) could be construed as a network of relationships. This view, in turn, goes back to Ferdinand de Saussure, who proposed that there are two ways in which language elements relate to one another: syntagmatically (as chains) and paradigmatically (as slots). Thus, in the table below (from George 1967), cheaply reproduced is a syntagmatic relation (it forms a chain), while maps, charts, and diagrams share a paradigmatic relation (they fill the same slot).

But, of course, they really came into their own with the advent of structuralism – the view that language (and not just language, but any cultural artefact) could be construed as a network of relationships. This view, in turn, goes back to Ferdinand de Saussure, who proposed that there are two ways in which language elements relate to one another: syntagmatically (as chains) and paradigmatically (as slots). Thus, in the table below (from George 1967), cheaply reproduced is a syntagmatic relation (it forms a chain), while maps, charts, and diagrams share a paradigmatic relation (they fill the same slot).

Substitution tables, then, nicely display these kinds of relations, and can be used to generate a great many sentences based on a single pattern. As George himself wrote:

Substitution tables, then, nicely display these kinds of relations, and can be used to generate a great many sentences based on a single pattern. As George himself wrote:

‘With these Substitution Tables you can speak and write many thousands of English sentences, without making a single mistake… After you have made a large number of sentences you will find that you have learnt the sentence pattern.’

Accordingly substitution tables featured prominently in materials that subscribed to an audiolingual methodology – i.e. one that was predicated on the belief that language learning involves internalizing the patterns of the language through processes of habit-formation, so that they might be reproduced accurately.

But substitution tables (as we have seen) pre-date audiolingualism. In 1916, Harold Palmer was already singing their praises, recommending that each sentence produced by the substitution table should be ‘examined, recited, translated, retranslated, acted, thought and concretized.’ There are more than enough suggestive ideas in this little (paradigmatic!) list to keep an imaginative teacher busy for many hours of productive classroom time. Let’s see.

Examined? Here’s how H.V. George suggests using his tables (having drawn one on the board or, nowadays, projected it):

‘The teacher starts by reading sentences from the table, choosing items which are easy to follow and reading slowly, but without halting at the columns. When most of the items have been used to the teacher increases the speed of begins to take items from widely separated positions. At this stage the teacher brings out a good student. As the teacher reads, the student points with a ruler at each item in turn. Following is not too easy if speed and range of items increase as the student becomes more proficient. One tries to keep the student under pressure without actually causing them to break down. Of course the other students are watching to see whether he does, and their interest is maintained. One or two students have a turn, then a student may replace the teacher, himself be replaced and so on.

A lively use of the table is for the teacher to point a ruler at one item in one column, at the same time reading aloud an item from another: and pointing to (or naming) a student anywhere in the room; the student having to form a sentence which includes both the spoken item in the one pointed to.’

Recited? Jazz chants, of course. Substitution tables share some of the characteristics of song and verse: short, repeated lines, with minor changes. Think of

The knee bone connecka to the thigh bone;

The thigh bone connecka to the hip bone…etc

Translated and re-translated? Students in paired groups A and B: each translates sentences from a substitution table and sends them (written or spoken) to the other group, who translate them back again.

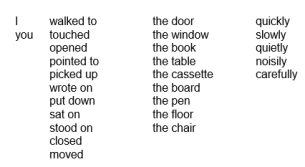

Acted? TPR, naturally. A student (silently) chooses a sentence from a substitution table (like the example below) and acts it out: the others guess what it is.

Thought? Have students construct their own table out of the jumbled elements (like a jigsaw puzzle), or out of a collection of sentences.

Concretized? Give the students a substitution table and get them to make as many sentences as possible. If this sounds too mechanical, insist they be true sentences. Or, ‘true for your group’. Then for fun, the activity can be turned on its head, by the substitution of the word ‘false’. Or ‘funny’. Or ‘surreal’. And so on. A competitive element can be added by giving a time-limit: How many true sentences about your group can you produce in three minutes?

Oh – and the argument I had with my editor? It seemed to me that she was conflating substitution tables with tables like this:

which is not a substitution table at all, in the sense that you can generate new sentences by combining any of its elements: *Who is your sister singer? *Are your favourite married? ??? Moreover, what often look like substitution tables are simply tables of verb paradigms: I am. you are. he/she/it is etc. In the end we compromised, and rather than saying ‘they have fallen out of fashion’, I wrote ‘they are less common nowadays’. And I added, ‘but there are few clearer ways of displaying a structure’s parts, and – with a little ingenuity – they can also provide a model for creativity and personalization.’

References

George, H.V. (1967) 101 Substitution Tables for Students of English, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

George, H.V. (1967) 101 Substitution Tables for Students of English: Teachers’ guide and advanced students’ guide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kelly, L.G. (1969) 25 centuries of language teaching: 500 BC – 1969. Rowley, Mass.: Newbury House.

Palmer, H.E. (1916) Colloquial English, Part I: 100 Substitution Tables. Cambridge: Heffer.

“One tries to keep the student under pressure without actually causing them to break down.”

Indeed one does!

Great post, Scott!

And don’t forget the next bit…

“…the other students are watching to see whether he does, and their interest is maintained.”

Hey everyone, let’s watch closely to see if he messes it up! Hilarious 🙂

Haha… yes, language learning as a blood sport!

Hi Scott,

You say today: “there are few clearer ways of displaying a structure’s parts” (than substitution tables), “and – with a little ingenuity – they can also provide a model for creativity and personalization”. This sounds like a recommendation to teachers to use substitution tables.

Two weeks ago, you reaffirmed your view that usage-based theories of language acquisition provided the best explanation of how people learn an L2. If language learning is the strengthening of associations between co-occurring elements of the language, and if “what starts as phonotactics ends up as collocation, morphology and syntax”, how does using substitution tables help the language learning process?

Thanks, Geoff. There seems to be no inherent contradiction in subscribing to a usage-based approach while at the same time promoting the use of what used to be called ‘consciousness-raising’ (CR) activities – and substitution tables seem like as good a way as any of bringing to conscious awareness the patterned nature of language – whether in the form of canonical grammar structures, or of what are loosley called ‘constructions’ (within the usage-based framework) – especially those constructions that are not otherwise salient in the language learners are exposed to and/or differ from those of the learner’s L1. In the old days, of course, substitution tables served the needs of a pre-selected syllabus of grammatical items. But they needn’t – they could just as well be derived from learners’ output, or from the texts that they are reading or listening to. Used ‘reactively’ like this, they could help provide structure to emergent language and thereby facilitate noticing. Also, the practice opportunities they afford (through the kinds of activities I mention) are consistent with the need for variable iterations that I talk about in this post: https://scottthornbury.wordpress.com/2013/05/19/r-is-for-repetition-again/

Hello Scott,

My experience seems to confirm your argument that substitution tables have fallen out of fashion. In fact, I only came across them after five years of teaching career and after two teacher training courses. Interesting enough, the first time I saw a substitution table was while reading “Teaching Unplugged” (p. 71) which seems pretty ironic as they seem to be the furthest thing from a Dogme approach. However, I agree with you on the fact they can be exploited for more than simple repetitive and boring mechanical work. I believe that the trick is creating open-ended ones, by leaving the learners some freedom on how to complete them. Individualisation and personalisation will make their use meaningful and stimulating. Furthermore, as you and Luke suggest, they can also be used as interesting stimuli for in-class conversation.

Thanks, Andrea. Regarding the incompatibility of substitution tables and a teaching unplugged approach – see my response to Geoff above. Another book I had a hand in – Teaching Grammar Creatively (Helbling) – makes considerable use of substitution tables as a device for generating personalized learner output within a ‘safe’ framework.

I teach academic writing courses and I’m a big fan of Dr John Morley’s “Academic Phrasebank” – a fantastic resource. He makes very effective use of tables to illustrate similar structures or phrases, though I’m not sure they could be classified strictly as substitution tables. Tables like these incredibly useful for illustrating the formulaic nature of certain structures (and of a lot of academic writing in general), and an excellent way of raising awareness of the recurrence of “phraseological patterns”, as he calls them in the introduction to the Phrasebank, in academic writing.

Thanks, Eoin – didn’t know about the Morley book but I will certainly chase it up. S.

Scott:

I am glad you included that Harold Palmer quote. In his 1959 “Technemes and the rhythm of class activity”, Language Learning 9, 45-51, Earl Stevick makes a similar point. He contends that teachers can manipulate every single class activity and tool in such a way that even the slightest alteration can make for an emic difference, a meaningful difference. See also, Diane Larsen-Freeman (2013) “Complex Systems and technemes: learning as iterative adaptations”.

In my BETA/FIPLV keynote in June called “From Roman to Möbius Bridges and Back: where are we taking (E)LT next?”, I made a comment that the moment something gets discredited, or interest wanes or attention wanders, we often abandon potentially very useful techniques & activities rather than tweaking them a bit.

As Stevick points out, there are 74 different ways or permutations of doing a simple dialogue — with books open or closed, standing or sitting, choral or individual repetition, repetition Lozanov style in a surprised, annoyed intrigued way (as we know from various studies emotions do help with recall and retention), we can do shadowing etc, etc.

In fact, new ideas are rarely, if ever, totally new – David Burkus ( someone that you like), an author who has written a lot on the myths of creativity rightly argues that all new ideas are built by combing ideas from already existing sources. The novelty comes from the combination or application, not the idea itself. An example he loves to give — the printing press used the technology of the wine press.

Gracias otra vez for another good, important posting.

Gracias, Elka. ‘Learning as iterative adaptations’ might be another name for substitution tables! Again, see my post in which I credit Diane with this leap in my thinking: https://scottthornbury.wordpress.com/2013/05/19/r-is-for-repetition-again/

Iteration is one of my favorite concepts too . : )). So rich, so important.

“…then a student may replace the teacher,,,”

Computers, robots, YouTube tutorials, and now George’s ‘tabling’ to get rid of teachers. We’re doomed…

Thanks for another fascinating post, Scott. I was intrigued by the early sixteenth century use of substitution tables, so I checked out the original source of your image, which is by Giles Du Wes, often referred to in the literature as Giles Duwes. The book came out in several editions, and the title is listed differently in different bibliographies, but is something like An Introductorie for to lerne to rede, to pronounce, and to speke Frenche trewly, compyled for ye lady Mary doughter to Henry the eight. Although I was able to find a pdf online, I was unable to find a title on it, but the author’s name is clearly spelt “Du Wes”.

If you look at the page you reproduced, you will see that it is not a true substitution table. I have transcribed the text at the top of the page and a sample line from the table:

Salutatyons in frenche / whiche may be tourned two maner wayes / as whan ye saye in Englysshe / God gyue you good morowe / ye may saye / Good morowe gyue you god / as ye shall se here folowynge.

God the gyue Good morowe the gyue god. [the = thee]

Dieu Te doit Bon iour Te doit dieu.

In other words, you can say, “Dieu Te doit Bon iour” or “Bon iour Te doit dieu.” Also, although, Du Wes supplies the other pronouns in the appropriate column, they are not all equally usable: I don’t imagine one said “Dieu Me doit Bon iour” any more than one said “God gyue me good morowe” in English.

Thanks, Nyr – and apologies for delay in responding. Yes, in fact Kelly (1969) makes a similar point about the Duwes table, noting that it has ‘some unnecessary duplications which show he was not sure of his tool.’ And ‘Notice that vo (vous) is unnecessary in the second half of the dialogue, as the following column gives a full range of possible pronouns.’

Hi Scott,

I can’t really comment as to the changing popularity of substitution tables, but I use them regularly in class, often in response to what’s happening as well as in a pre-planned way.

Professor ISP Nation refers to them in “Teaching ESL/EFL Listening and Speaking”, and in general I’m very attracted to his undogmatic approach to teaching and teacher training.

And they can be used to generate genuinely communicative activity too, for example by providing a template for questions and responses – my beginner students are really enthused to discover that they can make their own conversations from their very first class.

Interesting to see that Eoin uses them, or something similar, for advanced students too.

Thanks, Patrick – it’s encouraging to known that I’m not alone in my faith in the utility of these tables!