Rossini is supposed to have said of Wagner’s music: “He has some wonderful moments, but some terrible quarters of an hour”. I’ve observed (and taught!) lessons like that: some great moments but a lot of unnecessary time-wasting: over-prolonged warmers, games with little or no language output, instructions that take more time than the activity they’re designed to support, and so on. Time, I’ve come to the conclusion, is the single most wasted resource that teachers have available to them. And time is of the essence. The task of learning a second language is enormous. For many learners it is also expensive. To fritter the time away seems irresponsible.

Hence I’ve always liked the term “time-on-task”, since it captures for me an essential characteristic of good teaching: the capacity of the teacher to ensure that classroom time is optimized and that the learners are engaged in productive language activity to the fullest possible extent. This means, of course, that the learners know what is required of them – and there is a tension between, on the one hand, giving detailed instructions and, on the other, getting down to the task as quickly as possible. I knew one teacher who was dismissive about the need for clear task-setting. Her attitude was “Give them the material and let them get on with it – you can sort it out ‘in flight’”. I’m not sure I agree entirely, but I can see her point.

Likewise, I am suspicious of technology that isn’t already installed in the classroom and operational at the flick of a switch – or click of a mouse. Lesson time that is wasted in faffing about with cables and recalcitrant software is lost learning time. The same goes for games that require more explanation than their likely language affordances can possibly justify.

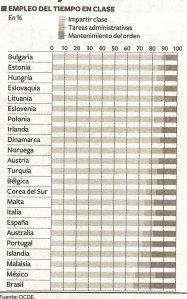

Faffing about, as it happens, accounts for big chunks of lesson time in mainstream classes, according to figures that were published recently in a Spanish newspaper. The chart on the right shows how much time is lost in routine administrative activities (‘tareas administrativas’) and in controlling the class (‘mantenimiento de orden’) as compared to actual teaching (‘impartir clase’) in classrooms in a number of countries worldwide. Fortunate are the students in Bulgaria, where only round 10% of time is lost, compared to, say, Brazil, where up to a third of the lesson is frittered away.

Some recommendations, then, for exploiting time effectively:

1. Develop a set of reliable classroom routines that students will immediately recognise and which therefore require minimal explanation;

2. Resist the temptation to front-end the lesson with lots of warmers and ice-breakers. Get to the point as quickly as possible!

3. Evaluate any activity in terms of the likely language production it will generate against the time it will take to set up. If the pay-off is small, ditch the activity, or think of a quicker way of setting it up.

4. Use only those tehnological aids that you are already comfortable with and which are already installed and easily accessible in the classroom, and – even then – measure their worth against the language learning affordances that they are likely to provide;

5. Set for homework those activities (such as reading, listening, and doing grammar practice exercises) that might otherwise cut into classroom time that could more usefully be spent speaking.

6. Use the students’ L1 to cut corners, e.g. in explaining an activity, in providing glosses for unfamiliar vocabulary, in checking understanding of a text, and even in presenting grammar.

7. Be punctual yourself – set a good example and impress on students the importance of starting (and finishing) on time. Likewise, don’t wait until the last student has arrived before you start the lesson.

8. With younger learners, reduce the time that needs to be spent maintaining order by keeping the pace of the lesson fairly upbeat, thereby avoiding the kinds of longeurs during which anti-social activity is likely to occur.

Any other suggestions out there?

I’ll pass over the ‘faffing’ comment, as I’m sure a certain someone will be along to comment sooner or later.

But for me, my start in teaching, I come at this from the opposite angle. I started teaching in private conversation schools… 50 minute lessons, tightly packed textbooks, planned to the second. When I moved into higher education I had to re-learn my concept of time. When you have the same students for three hours a day you have to learn to let the material breathe, you have a chance to take a diversion, you can spend time on rapport building, admin, and so on. Some time-wasting is productive in allowing students time to absorb what they have just done and to let their brains settle, no?

Hi Scott,

Yes, thanks for this really practical list of how not to waste valuable class time. This is perhaps a key point for effective classroom management and something that is worth keeping in mind especially when lesson time is as little as 3 hrs per week!

I’d like to add three more points.

Picking up from your point 5, I sometimes remind teachers that what is set for homework needs to be corrected in some way or another at some stage. So, perhaps as well as thinking about saving time during class, they can also consider and plan ahead how they intend to correct the hw, considering the level of the group, the age range and the relevance of the set hw in terms of the next few lessons.

Another thing that sometimes strikes me is that if teacher opts to use resources or realia, these need to be handy during the class – actually, it’s just a question of looking over the plan and bringing everything to class so you don’t need to run out and get things. Seems obvious, but it’s something that can be easily forgotten when teachers are toing and froing from one class to another.

The third point might be more country-specific, I’m not sure. In Brazil we already have lots of students with Special Needs in our private language schools and in mainstream schools and on the whole the teacher will have very little support. So, for those with SEN students in class, they really need to be aware of what additional resources, materials or plans will be needed. This is fundamental in order to ensure class time is used effectively.

Would love to look over the report printed in the newspaper, you don’t happen to have a url for it?

Thanks for your comment, Valeria. Regrettably, I don’t have a link to that data – it was printed in El País, the Spanish national daily, a few months ago. I’ll see if I can retrieve the paper copy and locate the original source.

A further thought about the source of the data – it comes from the OECD so I had a look round their website, and, although I couldn’t trrack down the time-on-task data, I did find some fascinating statistics comparing – for example – time devoted to different subjects across different countries. You can find the link here.

My favourite ever post by you, Scott. (And just after I blogged that you weren’t God! ho hum.) I was with you all the way until perhaps your last recommendation. There, I think, it really depends on the circumstances. I teach a ridiculously long 3-hour stretch for 5 and 6 year-olds at weekends. They would simply die if the lesson were entirely upbeat…and the last 30 minute fallout would be awful. Instead of keeping it ‘fairly upbeat’, therefore, I would suggest, instead, that the pace is varied with a sufficient amount of ‘downtime’ to maintain some sort of comprehension (consciousness!?) throughout the entire lesson time.

Thanks for the post.

Thanks Laura – and point taken about maintaning an ‘upbeat’ pace. Over a long lesson this would be a killer – for both teacher and students. (Darren makes a similar point above). I guess the challenge is making sure that the ‘downtime’ (so necessary for processing and reflection, as you say) doesn’t become ‘off-time’.

Damn! I thought T stood for teaching … or TEFL (Tradesman)!

Time is not a number on a page(or lesson plan)-it’s a person in the room.It’s almost as if you have to maintain eye contact with time,as its mood can change very quickly..There must be an equation somewhere which says something like:Time + Energy level=Pace.You have to vary the latter depending on the combination of the first two?

I agree with Laura, with young ones. Not only because of the need for things to be absorbed, but if your classes are non-stop upbeat, they’re likely to get out of control, so alternating ‘ups’ with ‘downs’ is more effective – physical movement with listening to a story, a class game with a worksheet of some sort, or a picture dictation. ‘dogme’ moments are also key to kiddies’ classes 😉 though may happen in L1; it doesn’t matter, if they feel comfortable, they’ll feed in the words in English they know, and speak a hybrid quite happily; thus they’ll tell you that they went to see their Granny at the weekend ‘y mi granny tiene chickens y three cats’ etc.

Another way of reducing wasted time, though, with youngies is by being careful with instructions – either show kids what you want them to do, rather than tell them, or tell them simply, and then ask a child to ‘check that everyone knows what we’re going to do’, and kiddy then tells you, if poss, in L1 what you want them to do. It saves repeating the instructions the same number of times as children in the room, or them all doing something quite different – and it also encourages them to listen in the first place if they think they might get asked to tell the class.

It’s worth doing something similar with lower level adults, as it also saves them the embarrassment of having to ask if they didn’t understand. My father’s learning Spanish at the moment, and he says he dreads a change in activity, because he rarely catches exactly what his teacher wants them to do, so he spends the first minute or so trying to spy on his neighbour and work it out….

Finally, when you do give instructions, ask for feedback, change activity etc, especially with young ones, getting everyone’s attention quickly is important – and not always that easy. I have a ‘signal’ (I never shout, or clap hands, or bang something on a table, but I’ve seen trainees do all of those… eek!) – I stand with my right index finger on my lips and my left hand in the air. Looks daft, but kids spot it, and have to copy it, and I don’t start to speak until everyone is doing it. It’s slow at the beginning, but they learn fast.

Hey Scott,

It’s nice to have an article which keeps us in check and reminds us of good practice.

Teaching one to one only, I find it can be all to easy to allow the lesson to descend into a chat without proper planning and a clear direction as to what we’ve set out to achieve. However I rarely find I’m in situation where the time has run away with me – quite the opposite in fact 🙂

Emma

Scott,

Like Emma, I second this post as an excellent reminder of teachers always remembering to make our class time valuable for students. So important for teachers to take this seriously.

However, that’s where I part with the “essence” of your post. Don’t your “recommendations” suggest some preconceived notion(s) of what a teacher IS and DOES? Doesn’t it also have a very lock, stock and barrel presumption about what learning is?

What I’m saying is that it all depends on the teacher’s set of beliefs and values (and I’ll refer to my great compatriot Stern for more on that. If the teachers visiting your blog believe in the same things as you – you’ll get a lot of nodding heads about this. If not, a lot of maybe yes, maybe nos. For me, some of your suggestions are great but others I question. I think that is because I have a different view as to how learning happens and more importantly, the role of a teacher in a classroom.

So what I’m saying in a nutshell is that your post is loaded. In a very general vein, all these things are good. But when we look at particular teaching environments, the learners in “x” classroom, the culture being taught and taught in – it doesn’t stick very well. (but this is what I love about teaching language – it isn’t legoland or rocket science, it is a human art).

When I teacher train, I wouldn’t put teachers into “X” set of procedures. Rather, focus on student’s needs at that moment or long term and balance them in your planning and delivery. So much of what we think of as “waste” in teaching is actually a diamond in the rough. I don’t have any figures but based on my years in the classroom, I’d say that what is planned and taught accounts of probably 10% of language learned. The rest is what isn’t planned, what is learned outside of the margins, in explanations and nuance etc….. We are motivators more than teachers, constructors of language.

For me, about the only good recommendation I can give any teacher about using time wisely is — get the students engaged as soon as possible. If they are thinking (and I won’t say “speaking” that is but the too obvious appearance of learning), they are learning. But even then, I have troubles with that statement….. you’ve got me in a funk and I thank you for that. As a man I so love, Primo Levi once said when asked how he got so much done, “time is infinitely compressible”. I think we have to remember this dimension of time ( which Luke I think was getting at).

Oh and let’s not forget that as teachers we aren’t just there to teach language – but that’s another topic.

David

David – thanks for your response – and challenge! It got me thinking, and I’m grateful for the opportunity to correct a possible misinterpretation of my original post.

I didn’t mean to give the impression that a good lesson is so well planned, or so packed with activity, that it runs like a Swiss train. Or that learning is a mechanical and incremental process. Or, even, that teaching causes learning.

On the contrary, I believe that effective teaching involves both spontaneity and chance, that it is (in Leo van Lier’s terms) both partly preplanned and partly locally assembled, and that “it is predominantly during unplanned sequences that we can see learners employ initiative and use language creatively” (van Lier, 1988, p. 215).

But unplanned sequences still need to be “timed” and “paced”, it seems to me, so as not to let them degenerate into inconsequential chit-chat. Likewise, allowing the learners a greater role in choosing content and directing the learning process still assumes the resourceful use of time. It’s too often assumed (it seems to me) that, just because learners are making noises in groups, positive learning outcomes accrue. The teacher is probably still the best arbiter of what constitutes productive as opposed to unproductive interaction, and the best judge of when to engineer a transition from one activity into another.

But I agree that – in the end – learning is unpredictable and serendipitous, and that the optimal learning environment is one that – rather than constrain learning opportunities – multiplies them exponentially.

I suppose that what we need to remember is that everything happens for a reason – to think why we are doing something in a lesson – as long as it is related to appropriate learning, then it’s OK (defining appropriate is another kettle of fish….).

I would venture to say that the difference between Dogme teaching and ‘Winging it’ is that…. when you ‘wing it’ you can’t really see how you are developing learners’ skills – a skilled teacher can deviate from their planned course and still make it beneficial for their learners.

“defining appropriate is another kettle of fish…”

True. One way of defining appropriateness maybe by reference to the learners’ preferred learning styles. Zoltán Dörnyei, in his book ‘The Psychology of the Language Learner’ (2005) quotes Yates (2000) to the effect that:

Dörnyei comments “the most effective way for teachers to demonstrate awareness of learning styles is to be sensitive to the students differential time requirements in coping with certain types of tasks… the idea that different students need varying amounts of time to achieve certain learning objectives is one of the most basic at the same time rather neglected principles of educational psychology ” (p. 158).

Thanks to Fiona who found the time to draw this discussion to my attention.

Rather pompously I often say: “People who say they haven’t time actually mean they do not how to manage their time. ” Really busy people, like Fiona, for example, somehow find time. In the classroom, of course, time management is very complex, much more like conducting an orchestra – albeit a small one – or directing the performance of a play – so many many rhythms, interactions, processes to monitor, initiate, further, augment, scaffold, afford – time. And as for warmers instead of getting straight to the point. I still have the comment a student sent to me years ago: “Dennis. When you say – ‘Before we begin’ – we’ve already begun.” Thanks for taking the time to read this.

I’m really enjoying this discussion and I just can’t resist a Dörnyei quote!

The ‘differential time requirements’ mentioned above become particularly apparent with (relatively) large groups (25-30 in a University language school). I find that time requirements often have little to do with ability, although there is sometimes an age factor (I’m taking longer to process information myself these days).

I sometimes feel like a conductor dealing with different sectors of the group, managing the pairings and seating combinations to optimise effectiveness, facilitating in this section to bring it into time with the others, trying to slow down the over eager and encourage reflection, reformulation and checking in others. Ideally, bringing the whole task session to a rounded, satisfactory conclusion.

Other contributions have mentioned the ‘feel’ for timing that you develop as a teacher. I understand this to mean sensing student engagement by task progress, monitoring body language and even volume. Working with confident, adult students I sometimes find it useful to just ask if they’ve had enough time. They even negotiate ‘extensions’ with each other on occasions, though I’m aware this would not be appropriate in other contexts.

Dennis, that’s a great comment. I was thinking about the warmers and breakers too and in my opinion it’s really the question of what kind of warmers you use, in what way they are connected with “the content” of the lesson, how you use them and how the students react and also what kind of lesson it is (I have one YL group with whom I have to use warmer-like activities most of the time as they give me the cold shoulder otherwise). So some of my lessons are composed mostly of warmers, breakers and team building activities planned in a very careful way… But I’ve also seen teachers doing warmers and breakers with no visible point.

Marta. Thanks for your comment. Looking for something quite different on an old laptop, by chance I came across a piece on time that I want to share.

———

David mentions one master. Another, in a different league, was the colourful Lionel Billows, author of the classic: The Techniques of Language Teaching, Longmans, 1961 ISBN 0 582 52605 5, sadly out of print. At some time in his career Lionel wrote several hundred short personal pieces for teaching purposes. They were never published. Here is one on time. Towards the end you should see why I am posting it here.

Dennis

——-

Lesson 1

I usually get up at 6 o’clock, make tea and give the children breakfast, in time for them to catch the train for school. But on Saturdays and Sundays, when the children don’t go to school, I get up later, at perhaps half past seven or eight o’clock.

My wife had an alarm clock; she set it every evening for the next morning, but a few weeks ago it broke down and the clockmaker says he can’t repair it. So I rang up the telephone operator and asked her to wake me at six o’clock, but I woke a quarter of an hour earlier. This happened several times, so I decided to do without the telephone and save the money. Now I wake every morning at six, if I tell myself, before going to sleep, that I want to wake punctually at six. If I don’t do this I sleep on till eight or nine o’clock. So on Saturdays and Sundays I sleep late, and I’m happy to know that I have such a good clock inside me.

But this internal mechanism doesn’t only work in sleep in the night, one seems to set it by getting used to a particular activity, lasting a certain length of time: for example, a cooking pot full of leeks or Brussels sprouts needs fifty minutes, after it has boiled, and one has turned down the heat from two to a half on the electric cooker. One sits down with a book or a newspaper, and after fifty minutes one gets up, almost unconscious of why one has got up, and goes in a half- conscious state into the kitchen, sees the pot boiling and realises why one is there.

For years I was used to talking for fifty minutes, and then inviting questions for ten minutes. Then I started lecturing for an hour and a half, so that now, when I give a lecture, it lasts for an hour and a half. The material is arranged in my mind accordingly; a few more examples, perhaps a few more sketches on the blackboard have made their way into the basic concept.

Once, at an international conference I was not in the programme, but in a working group some remarks I made, or questions I asked aroused interest. I was asked to talk for ten minutes. I did so, and sat down punctually after ten minutes. People seemed astonished and asked “How did you do it? Usually when a person is given ten minutes to talk, he talks for half an hour.” I answered: “I know what I can say in ten minutes and I know what it takes half an hour to say; I don’t let one interfere with the other.” All this seems to prove that the measurement of time takes place in the subconscious mind, based on a time-scale that has been calibrated or adjusted to particular, often repeated experience or needs.

—————-

When planning I find it’s useful to not over plan or over pack a lesson with activities. Very roughly – an opening phase to “activate schemata” a “task phase – including instruction/demo and monitoring to check they’ve understood” a “focus on emergent language/or focus on structures useful to the task phase” and another “task phase” to provide the opportunity to integrate language items and possibly a presentation/report phase (as in the TBL cycle)

When to move from phase to phase depends entirely on the individuals in the group.

Occasionally the whole plan may have to go out of the window if the initial phase evolves into a very student centered discussion with appropriate teacher language input. Sometimes the middle phase “focus on language” may need to be longer, with recognition activities such as underlining the particular discourse feature in a text, appropriation activities such as drills/games/pron work. Sometimes it may not be so long……it all depends on what arises in the initial stages and the people in the room. So the teacher can respond to what comes up.

Regarding timing – when to change stages……there’ll be some students who would just chat all night long, but others who you can “feel” are “ready for the next stage” as long as they have grasped and participated in the task, I’ll often “feel” those students and then change pace/activity accordingly. (Same principle in workshops)

I suppose what I’m trying to say, is pretty much what David expressed. In particular this part:

“When I teacher train, I wouldn’t put teachers into “X” set of procedures. Rather, focus on student’s needs at that moment or long term and balance them in your planning and delivery. So much of what we think of as “waste” in teaching is actually a diamond in the rough. I don’t have any figures but based on my years in the classroom, I’d say that what is planned and taught accounts of probably 10% of language learned. The rest is what isn’t planned, what is learned outside of the margins, in explanations and nuance etc….. We are motivators more than teachers, constructors of language.”

This makes me think of the person I really felt most confident speaking and learning German with in my early days here. It wasn’t my German teacher, it was a friend of the family who has the most incredibly patient manner and used to sit with me, talk, really listen to me without judging and then constantly reformulate what I was saying. After spending a weekend with this person, I would feel much more confident at German.

So the time in the classroom on unplanned talk, is I suspect very valuable for particular types of learners.

I’m wondering if the study in the paper was concerned more with traditional subjects such as Geography and Biology, where chit chat really might take away valuable time from getting down and learning about the topic. But in English – surely as soon as you start speaking there is the input, there is the topic of study……..then what do we do with it, that’s the question!

Hi Scott (and everybody),

it’s been my experience that a lot of time gets wasted (or, rather, used unwisely) when giving feedback to students, as it seems to be the one part of the lesson which is often overlooked by many teachers (I myself am guilty of this) when planning.

What I mean is that I think often, in the planning stage, we think about how we’re going to set up the activity, the groupings of the students, etc, but not how we intend to provide meaningful feedback to the students once the activity is over.

I think this is often apparent when I observe teachers giving answers to activities from the coursebook, where the instructor goes through the usual “Number 1? Anyone? Anyone?” instead of just putting the answers on the OHP and using the time to react to the students’ questions and problems, rather than address every item (many of which the students had no problems with).

John,

Excellent point and those kinds of efficiencies (and even sending students online to check quiz answers etc…) are what teachers need to do a lot more… not enough sparkplug and too much flywheel.

Scott,

I never thought for a moment that you didn’t cherish and value “the teaching moment”!!! I’ve been to your presentations and this shines forth for the most part.

However, it is a kettle of fish but one that pays a lot of dividends for the teacher that thinks of them. I thought about all your points and my own teaching. Only 2,3 and 7,8 really make my heart skip a beat. But that’s me, for others, they will value other things. I do agree that we should value and honor time but at the same time, we shouldn’t wash its feet – if I can say it like that…. same thing I guess goes with planning. We should plan but never just stick to it – it is but a crutch until the starter’s pistol goes off and its time to REALLY run.

I also think that a classroom is a democracy. You allude to that. The teacher is the “primus inter pares” , the first among equals, who makes the decision(s) for the group about pace (with the object of reaching some goal – even if it is just your notion of “time on task”.

However I started this reply because of your ” the teacher is the best arbiter” comment. I think usually teachers AREN’T the best, just like in our politics. But we are stuck with ’em. A kind of compromise. I really wish there was a better way…..

I appreciate the Dornyei mention/quote. I’m as big a fan of anything/anyone touching of Hungary as there be on this earth. (Koestler’s work should be read by any serious student of linguistics but there are so many other Magyars).

I don’t think your blog on “Time” would be complete with a quote from the meister of time himself, William S. – I’m on his side, against time and the tick tock and on the side of quality, repose and pleasure in teaching.

And do whate’er thou wilt, swift-footed Time,

To the wide world and all her fading sweets;

But I forbid thee one most heinous crime:

O, carve not with thy hours my love’s fair brow,

Nor draw no lines there with thine antique pen;

Him in thy course untainted do allow

For beauty’s pattern to succeeding men.

Yet, do thy worst, old Time: despite thy wrong,

My love shall in my verse ever live young.

Sonnet 19

Scott,

thank you, thank you, thank you… for point 6 🙂 I always have a discussion about it with teacher trainers in the schools where I teach. Because I have a strong feeling that in many cases explaining the rules of a game, an activity etc or some vocabulary in L2 is a waste of time. I actually feel that if you are a NEST then explaining and understanding the rules needs to be done in L2 and it is a part of the activity. However, if you are non-NEST it is very frustrating for the students if they don’t understand and you insist on speaking L2 (and they just want to start the activity). Of course the teacher trainers have different opinions about it, they claim that we should use English ONLY as pretending that we are NESTs 🙂 So every time I read an opinion like yours I feel supported.

A footnote on the subject of ‘time’: I attended a workshop at the Eastern Mediterranean University Conference here in Cyprus yesterday, where data on students’ perceptions of classroom management was presented. One of the features of management that was rated very highly by students was the teacher’s capacity to start the lesson on time.

I might add (from my experience at this conference and many others) it’s also a characteristic of good presentations that – not only do they start on time – but they finish on time too, so as to allow participants to get to the next session, or to take their place at the head of the coffee queue!

It’s funny, and sad, how Brazil tends to be at or near the bottom in such surveys, somebody has to be there though.

It’s also interesting that two weeks ago one of the major magazines in Brazil published a cover article titled ‘the secrets of good teachers’, and efficient time management was regarded by the teachers (not the students) as one of these secrets. Some school administrators said that a good teacher is able to cover 1,5 years in 1. I disagree of course. A good teacher will cover 1 year in 1, and if there’s time available, s/he should spend on filling the many gaps the national curriculum has and not advancing on it.

Back to ‘time’ and the relation between this survey above and this article, it was mentioned that a lot of time is wasted on attempts to keep the class quiet and focused, and with ridiculous things like a teacher nagging students to take off their hats. (I know, I was one of these students). All in all, this article celebrated these teachers who could keep the order, being in 2010 this is weird, because this so-called order means everybody silent and listening to the ‘master’.

I don’t want to be long here, so I’ll briefly comment on Scott’s footnote just above. “The teacher’s capacity to start the lesson on time” is also rated highly by students in my institute, but they rarely criticize HOW class time is administered by teachers. Weird.

Great post!

Yes indeed:

But at my back I always hear

Time’s winged chariot hurrying near

And yonder all before us lie

Deserts of vast eternity.

I do think this is really important, and a lot of excellent points have already been made. To these I would only add that – in my experience – the more carefully the lesson has been planned in advance, the more genuinely useful on-task classroom time appears to end up wasted (though this could just apply to me). By that I mean that being too sharp and moving on too quickly in places (to keep up with our careful allotments of time for different tasks) can make it feel like we are being effective when in fact we may be doing the opposite.

Going with the flow of a lesson, learning how to control the tempo and rhythm in the right places, is as important a consideration as any when it comes to effective use of language learning time.

I particularly like points 2 and 5 on your list, Scott.

Cheers,

Jason

Perhaps I have not read all contributions carefully enough, but one aspect of the discussion on time that disturbs me a little is that it encourages the focus to be on what the teacher teaches, or organises or affords or scaffolds, and not on what the learners learn. Talking about teaching instead of learning has this effect: “How long should I, the teacher, spend on…? ” instead of “How long should the learners….?” I am reminded of the old-fashioned formulation – TTTv. PTT – teacher talking time versus pupil talking time. ( I realise these days everyone speaks of “students” when they are referring to kids at school, but I stick stubbornly to ‘pupils’ for school and ‘students’ for colleges and universities.)

Dennis

Time is an extremely culturally bound notion, arriving and leaving on time especially. You can try to set norms for your lessons, but be sensitive to how and why the students don’t always share your idea of why this is important.

Interesting caveat, Adam. Are you suggesting that students’ perception of the importance of starting and finishing a lesson on time might correlate with culturally-embedded notions of punctuality? Do some cultures display a greater tolerance of time-wasting? I’m nervous that this line of thought leads to cultural stereotyping, but if anyone has any concrete evidence that “[classroom] time is an extremely culturally bound notion” I’d be interested in hearing it.

You can insist on punctuality in Spain if you like … if you want to finish up with a stomach ulcer. Remember King Canute?

Great article on Time.

I have a problem with too much time. I have to teach 5 hours a day and I’m struggling to make all of those hours meaningful.

Related to that and Point 5, I find that having the students do reading and writing tasks in class actually mean that they get them done; because after a 5 hour day, they hardly have the energy or motivation to do more work.

I agree with Adam, Time is of course everything, but I´ll go out on a limb here and suggest it´s the students responsibility to manage their time and learning and not the teachers. I think students should be able to stroll into class whenever they like, catch some one on one time with a tutor, and then do whatever they want to do. Then, they will never be late, right? Late – should be banned. Everyone walks to a different beat, so why don´t we provide the platform that allows every student to study when and where they want. Let them study at home, at the beach, at their mates place. And when they want some social time, they can head into the classroom and chat with their teachers, and friends. Some students might finish their studies in 2 years, and others 5 – but who cares how long it takes. Teacher led learning, is the past. It´s draconian – forget about time, and let the student be responsible. By the way, Brazil probably sits at the bottom of the heap because students, executives, and every other sector of society is permanently late. On the flipside they´re some of the hardest working people I´ve ever come across.

I’m a bit late joining this conversation, but still found it very interesting. It really helped me get my thoughts together about timing while planning to write a post on the same subject, so thanks!

I agree about reducing wasted time in lessons – we’ve all got habits as teachers and we often aren’t aware of how much time we’re wasting!

I tend to agree with Dennis above, as well. Lots of the time, of course, teachers who don’t get through what they had planned for aren’t necessarily wasting time. They are doing lots of great stuff – responding to learners, upgrading language, error correction, extending conversations, feedback, etc. It’s just that we need to plan for flexibility and manage timings in real-time. i.e. as opportunities for learning and communicating arise in a lesson.