In the debate sponsored by the ELT Journal at this week’s IATEFL Conference in Liverpool, I proposed the motion that published course materials do not reflect the lives nor the needs of the learners.

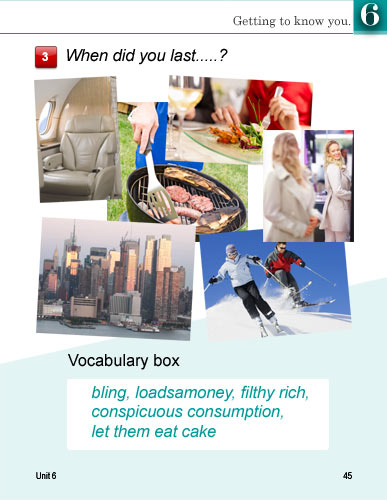

To challenge some of the assumptions inherent in much published teaching material, I used this mock-up of a coursebook page (see below). It wouldn’t have been ethical, or even legal, to have shown, and then criticized, pages from current coursebooks, but I think you’ll agree that the replica is a plausible one. I used this to argue that the choices, both of images (more often than not taken from the same kinds of photo archives as the images used in advertising) and of the text accompanying the images, serve to ‘position’ the user to assume a certain kind of identity with respect to the language that they are learning.

The physically-attractive, ethnically-mixed, well-dressed and youthful characters are surrounded by iconic consumer items that reflect their upwardly mobile, middle-class aspirations: they exemplify the observation made in a recent survey of general English courses by Tomlinson and Masuhara (2013: 248) that ‘there seems to be an assumption that all learners are aspirational, urban, middle-class, well-educated, westernized computer uses.’

Moreover, the questions they are asking – and the language choices available to answer them with – make certain assumptions about their (and, by extension, the student’s) economic status, sexuality, and agency. As I pointed out, somewhat facetiously, the questions Are you married? What’s your job? and Where do you live? do not invite, and may even preclude, a response along the lines of: Actually I’m gay and unemployed, and I’ve been sleeping on the sofa at my folks’ place ever since the bank re-possessed my apartment. And you?

As it happens, a search through a number of intermediate-level coursebooks widely used in Spain finds little or no reference to an economic situation in which 50% of under-30s are out of work. The words unemployed, on the dole, out of work simply do not appear. Struggle, inequality, deprivation, etc have been air-brushed out of the picture. As the authors of a survey of general education textbooks in the US note: ‘The vision of social relations that the textbooks we analysed for the most part project is one of harmony and equal opportunity — anyone can do or become whatever he or she wants; problems among people are mainly individual in nature and in the end are resolved’ (Sleeter & Grant, 2011: 205).

The cheery, sanitized, even anodyne, world of the coursebook has, of course, been endlessly targeted for criticism. In fairness, it is not the fault of the coursebook writers themselves (who generally would love to include more ‘edgy’ content), but more an effect of the constraints that they have to work within. These include the authors’ guidelines that many publishers impose, including the famous ‘PARSNIP’ proscriptions (no Pork, Alcohol, Religion… etc). As Diane Ravitch (2004: 46) points out (with regard to textbook production in the US) , ‘the world may not be depicted as it is and as it was, but only as the guideline writers would like it to be’.

The ‘erasure’ of particular, potentially problematic representations – such as those of minority ethnic groups in Russian language textbooks (as reported in Azimova & Johnston 2012) or of Canadians in US-published French language textbooks (Chappelle 2009) – is seen as a deliberate, ideologically-motivated attempt to ‘rewrite’ history and demography. Hand in hand with this erasure of difficulty is found what Gray (2010: 727) describes as ‘the new salience of celebrity in textbooks’, indexing a neoliberal agenda that associates the use of English with success, individualism, glamour, and wealth.

However we view it, the way that the learner is represented (or not represented) in the materials they use, has strong ideological ramifications. As Asimova and Johnston (2012: 338-9) put it:

Representation is a highly political business. By this statement we mean that, consciously or unconsciously, those who create and distribute representations play a central part in power relations, challenging or, more usually, reinforcing existing hegemonic relations. Another way of looking at this issue is that representations are never neutral. Though they often seem “normal” and, in the case of visual images especially, can be hard to challenge (Postman, 1993), representations are highly ideological and are a crucial component in forming, maintaining, and changing our view of the world, of groups of individuals, and of the relationships between them. Relations of class, gender, race and sexual orientation are among the most important relations that are centrally mediated by representation.

This, then, was the gist of the case I made: arguing that the way that learners are represented in published materials is both ideologically motivated and out of synch with reality .

In defense of these representations, what arguments were offered by my opponent and in the open discussion during the debate? Here are four:

1. Students don’t want to be reminded of their less than perfect lives: the view through rose-tinted spectacles offers some respite from the general grimness in which they live;

2. The aspirational culture instantiated in coursebook images and texts has a strong motivational charge, and represents the sort of ‘ideal self’ that some scholars (e.g. Dörnyei 2009) argue is the prerequisite for success in second language learning;

3. All learning involves first identifying (proto-)typical examples of a behaviour, and only later accommodating more marginal phenomena. Hence the need to start with exemplars of the ‘norm’: e.g. white, middle-class, heterosexual family structures, before engaging with the ‘exceptions’;

4. It is not for the textbooks to reflect the reality of the learners’ lives (an impossible task anyway), but for the teacher to mediate – and exploit – the ‘reality gap’, by, for example, having the learners interrogate the texts and even subvert them.

Which way would you have voted?

References:

Azimova, N., & Johnston, B. (2012) ‘Invisibility and ownership of language: problems of representation in Russian language textbooks,’ Modern Language Journal, 96/3.

Chappelle, C. (2009) ‘A hidden curriculum in language textbooks: Are beginning learners of French at U.S. universities taught about Canada?’ Modern Language Journal, 93/2.

Dörnyei, Z. (2009) ‘The L2 motivational self system’, in Dörnyei, Z., & Ushioda, E. (eds) Motivation, Language Identity and the L2 Self, Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Gray, J. (2010) ‘The branding of English and the culture of the New Capitalism: Representations of the world of work in English language textbooks,’ Applied Linguistics, 31/5.

Ravitch, D. (2004) The Language Police: How pressure groups restrict what students learn, New York: Vintage Books.

Sleeter, C. E., & Grant, G. A. (2011) ‘Race, class, gender, and disability in current textbooks,’ in Provenzo, E., Shaver, A. & Bello, M. (eds.) The textbook as discourse: sociocultural dimensions of American schoolbooks, New York: Routledge.

Tomlinson, B., & Masuhara, H. (2013) ‘Survey Review: Adult Coursebooks’, ELT Journal, 67/2.

Thanks to Piet Luthi for the mock-up.

You can watch a recording of the debate here:

Interesting points!

First response: Bring on some controversy, if it does in fact provoke conversation and thoughtful discussion.

Second response: I vote for representations of reality from multiple points of view. Maybe not the most painful aspects of reality, until or unless learners bring it up. Sometimes it’s too fresh… but when learners readily ask some of the questions posed here and debate the images presented to them, that might be a way to judge a learning session as both successful and useful.

Thanks, Cyndi – yes, I like the ‘multiple points of view’ notion. When you think of it, this is what happens on blogs. And it also happened in the debate, where the 20 minutes of comments from the floor produced multiple points of view. How could that multiplicity be reflected in coursebook texts, I wonder? If texts were delivered digitally, with a comments stream (like this) would that improve matters?

Wow…I love that idea of digital textbooks with a comment stream. Think of the endless possibilities and roads of classroom discussion, and then students adding their own comments. that would be a true acknowledgement of the fact that knowledge is truly constructed and not “given” as a pre-determined body.

Thanks Scott for sharing your unit here. As one of the coursebook authors who has tried to buck the trend of aspirational lifestyle content in published materials I’ve had ample time to reflect on this matter too. In the end during that debate I found myself voting for the motion, that is supporting you, but I believe the four points you outline in opposition are all valid.

The other problem I found when writing more critical material (either for a publisher-mediated coursebook or for my own materials) is that there is a danger that such material can become very heavy-handed and, in the words of a good editor and friend of mine, “too earnest”. Put in the hands of an inexperienced teacher this becomes even more a case of otherizing (e.g. ‘now class, today we are going to learn about POOR people’). Not to say it isn’t important, but I think it’s very difficult to do it well.

Thanks, Lindsay – yes, that’s a good point: the heavy-handedness, I mean. On my MA course last summer we were doing a similar kind of critical deconstruction of some coursebook materials, and one of the students referred to an iconic character in American children’s fiction ( I think) called Moany Mary (or something) – the archetypal wet-blanket and exact opposite of Pollyanna, who turns every fun activity into an excuse for remorse and recrimination. (Emilia – if you are following this, can you remind me what the character is called?). Well, you get my point, I hope.

Debbie Downer?

Yes, that’s the one!

For those (like me) who don’t or can’t follow Saturday Night Live, this is the reference: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Debbie_Downer

Hi Scott,

For me, your post has helped conceptualize what many of us do anyway. I think this is particularly important when we teach groups who are being demonized in public narratives. It changes over time, but there always seem to be people we’re supposed to be wary of and about whom it’s acceptable to make ignorant generalisations; Jews, blacks, the Irish, Polish, Bulgarians, Muslims… No doubt learners from the affected communities have an acute sense of the narratives and the atmosphere/alienation they generate.

Come to think of it, some of my most interactive lessons have addressed societal attitudes to different cultures or ‘taboo’ subjects, and we all leave with new insights into each other’s experiences. However, to work well, it does require quite an open, tolerant atmosphere (starting with the teacher!). Your post has motivated me to do it more often and, yes, I’ll probably need to make my own materials…

Thanks, Mumtaz… yes, to work well, such discussion assumes a classroom dynamic conducive to expressing potentially conflictive opinions. It also – of course – assumes a level of English that can convey the complexities and subtleties of these opinions – and there is perhaps nothing more frustrating than being unable to defend an affront to your identity through lack of the requisite language skills. And, while coursebooks are organized according to a graded sequence of grammatical structures and high frequency lexis, it’s always going to be difficult for a beginner to express the finer shadings of their identity without at least some support form the teacher. Nevertheless, it irks me that the typical unit on family relationships doesn’t include the term ‘partner’ as an option for learners to describe their meaningful other. Nor do you find ‘Muslim’ very early on in a course, do you? There are certainly few overt visual portrayals of Muslims in most coursebooks. (Where are the girls and women with headscarves?) What was once referred to as invisibility (especially with respect to gays) is now called – more confrontationally, perhaps – ‘erasure’.

Thank you Scott for digging deep into this point.

I think this is even more relevant in the context of content language teaching. Looking closely at some materials used in such classroom, I find myself shocked at the number of anachronisms, misleading comparaisons, and a flood of bulk adjectives. Equally annoying is the heavy reliance, in the absence of an alternative, on the news as a source of authenticity

How Does It Feel to Be a Problem? by Moustafa Bayoumi gave a few classes lots to talk about in terms of immigration, identity and discrimination. The title raised eyebrow, a good start!

Thanks, Cyndi, for this reference. For those who don’t know this book, here is a bit of the blurb (from the Amazon site):

(This text, on its own, is ripe for critical discourse analysis!)

Thanks Scott for sharing a snippet of the debate, and the link to watch it.

Reading you I couldn’t help but project myself in the mind of a future academic or historian looking back at what people studied in the late 20th and early 21st (note I say ‘early’, hoping it’ll all change soon) centuries and couldn’t help but cringe. That same feeling we get when we look through material of the early 20th. Then a question came to mind, ‘So, did we ever get it right?’ Has there ever been a stage when course books fitted their period? I must say that I tend not to stick with the course book, but rather either select more suitable material here and there, or produce my own. Ultimately, it looks like the solution lies in the unplugged path – adapted or raw,

I would’ve voted for the motion.

Thank you, Hada. As I said, at the beginning of the debate – the issue wasn’t really about coursebooks vs no coursebooks, but it’s difficult to separate the question of ‘unrepresentativeness’ from the question of relevance, and, by extension, usefulness. After all, this is the reason that Sylvia Ashton-Warner (teaching Maori children in New Zealand in the 1960s) abandoned the mandated primers that had been written, illustrated and published in England, and started producing her own materials based on her pupils’ lived experiences.

Actually, I would have like to vote for the both parties in this debate – I think there are good points on either side!

It’s important to have these discussions to make sure teachers are aware of the issues and (if their syllabus allows) can include activities and materials that balance out such faults with the course books.

Certainly, encouraging students to speak and write about what matters to them and then using the course books images to provoke discussions along the lines ‘is it easy to relate to these people?’ ‘is it important to own these objects?’ etc etc, may go a long way to making the learning more personal.

Thanks, Avi – yes, this is what I was getting at when I referred to interrogating, and even subverting, the texts. Maybe an interesting classroom activity might take the form: Let’s remake this page (in the coursebook) using our OWN images and texts.

Great idea about students remaking a page – will definitely try this. Thanks

Were you able to resolve the untenable position that such a postmodern approach creates and that Geertz discussed way back in 1988: “The gap between engaging others where they are and representing them where they aren’t, always immense but not much noticed, has suddenly become extremely visible” (p. 130)?

Geertz, C. (1988). Works and lives: The Anthropologist as author. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

I am intrigued by this quote, Eric, but short of hunting down the source, I’d be grateful if you could expand on it!

Surely what is more offensive than the neoliberalist agenda in course books is the lack of imagination apparent in putting them together. The content and tasks are in the main, blindingly banal. I’m not going to invoke Sturgeon’s Law as the cause of this lameness, because that would be unfair on the people who design these books. But perhaps it is a reflection of the corporatization and commoditisation that blights ELT publishing. This means that teachers have to be the agents of change in this respect, which is not too hard when you consider the feeling of revulsion these materials arouse in many teachers naturally. This is similar to the effect of the uncanny valley / frankenstein complex in robotics, whereby the more publishers try to make their materials realistic, the more they defeat themselves by building an uncomfortably glib illusion that stares back at us, and likewise whom we can see through and subsequently reject. Perhaps it would be better if content creators led us into a learning world of fantasy, animation and fictional narrative with overt moral lessons rather than trying too hard to recreate reality embedded with covert messages. Ironically, that’s more human, or at least more appealing, but maybe that kind of reframing is too radical for the lumbering industry behemoths to conceive right now.

“Perhaps it would be better if content creators led us into a learning world of fantasy, animation and fictional narrative with overt moral lessons rather than trying too hard to recreate reality embedded with covert messages”

This is a novel – and challenging – point of view, Luan. I suppose one problem with such an approach (i.e involving fantasy) would be that the vocabulary that the learners would be exposed to might be a far remove from their everyday needs.

The content would have to be written to purpose. I think the way to do it is to present the language in a more meaningful way initially as part of a story, and then combine that with explanations, activities and testing. Narrative-based language is better because it can more easily combine intellectual and, for want of a better word, spiritual, content. The emphasis on skill development comes through interactivity with the text, particularly in game play. The good thing is this is more possible now because technology is changing the definition of what a book is; through enhanced interactivity and a blurring of the lines between media.

This obviously contrasts with ‘representative’ course books that are overt with the language — grammar mcnuggets and such, but often rather weak or uninspiring on the content side of things. As an opponent of cliched and formulaic notional-functional-type approaches, I would argue that escaping from the dullness (or fake glamour) of everyday life is precisely what is required for learners. At the root if this is that I’m keen not to patronise people, nor dumb things down unnecessarily.

Thanks for that clarification, Luan. I know that Marcos Benevides has had some success in using narrative structures as a framework for (print-based) course materials.

Your mention of ‘glamour’ also reminds me that (allegedly) glamour and grammar share the same etymology. I wonder if it’s only the infamous Asian phonemic problem that has prevented a publisher naming a coursebook ‘Glamour’. 😉

Interesting too that grammar/glamour originally meant magic. Spell and spelling also have shared etymology, I guess. Good title for a course book: Magic Spells 🙂

Here’s a link that challenges the shared etymology – pity!

http://linguistlist.org/issues/6/6-1197.html

Thank you, Scott, for pointing these out, what an interesting debate.

After 10 years of freelance full-time teaching I too oppose the “ideal” world of coursebooks and not only that. I also consider the structure of the coursebooks demotivating for a learner.

Both the representation and the structure do not reflect the 21st century reality. Our lives are not linear, our learning is not linear, language is mainly learned through social interaction, just like our mother tongue. I strongly believe language should be learned primarily via speaking, and it should be highly individualized, just like everything else we learn.

I focus on error correction, real-life activities, use of visual materials (authentic video and audio) and, last but not least, lots of interaction with fluent English speakers. After many years of using coursebooks I am happy to see my students, now liberated from coursebooks, learn much faster this way and they finally fall in love with learning a foreign language. They are motivated to surround themselves with the language every day and I miss this type of motivation in the coursebooks.

Thank you, Nina. It sounds as if you are a signed-up ‘dogme’ practitioner, without necessarily knowing it!

I watched and enjoyed the debate and would have voted for you, Scott. I’ve always been of the opinion that EFL course book publishers, in their zeal not to offend anyone, end up insulting everyone’s intelligence. Certainly some topics have to be handled delicately, but it’s not impossible.

I teach Business English at a university in Switzerland. Last week I wanted to work on the language of describing graphs and charts and I brought in a collection from The Economist. One of the graphs showed a world map of countries in the world where same sex marriage is fully recognized. The students handled it with aplomb. Nobody ran screaming from the classroom, or complained about the topic. Not everyone agreed, but it was a respectful and profound discussion. I suspect that one factor was that I presented the topics with the emphasis on “this gives us a chance to practice talking about trends” and not “now we’re going to debate some hot-button issues.”

I suppose I am lucky to be able to avoid the world of bland course books!

Thanks, Cindy, for that interesting insight into how potentially controversial material can be incorporated into otherwise conventional lessons. It would be interesting to take this approach a stage further and – for instance – design many of the example sentences in a student reference grammar to encapsulate alternative models of social behaviour, e.g. ‘Dave and Jerry have been married for two years now’. Do you think Raymond Murphy could be persuaded? 😉

I don’t know Mr Murphy personally, but in any case, judging by the comments here, even if he would go along with the “subterfuge” his publisher would certainly not allow it! What I like about this approach is that it takes the spotlight off the “hot-button” and treats alternative models of social behaviour as if they are just normal…which obviously they are. This is how I handle things in class when potentially controversial topics come up too. Stay calm and reasonable, and students will too.

Dear Scott, Dear Cindy,

Am a bit late commenting here sorry about that – just some thoughts:

1.Scott, would definitely vote for you – course books (even the best intentioned) are not representative of our students, their lives and their needs. I recently reviewed one of the course books I’ve been using (and is rather popular here in Switzerland for BE learners) and noticed that of the student’s book 42 pictures (of humans), 31 pictures (or 74%) are exclusively of Caucasians. White men are portrayed as business people, rich retirees, lawyers or doctors. White women are also depicted as business women (but mostly as secretaries). Only 11 pictures feature non-Caucasians, namely:

• 3 pictures of Asian businessmen

• 1 picture of an Asian business woman

• 3 pictures of poor Latin field workers

• 3 pictures of impoverished Africans and 1 picture of an Arab in typical Bedouin clothes.

Worst of all, I never really realized this until I took the time to thoroughly analyze the book.

2.Even if Murphy and other publishers aren’t convinced to include sentences which reflect our realities (like the one you mentioned: “Dave and Jerry have been married for two years now”) other online dictionaries and sources are noticing and starting to change. NPR recently featured a story “Gay Marriage and the Evolving Language of Love” which shows how language, terms and expressions are changing to reflect the changing world.

http://benzimmer.com/weekend-edition-npr-gay-marriage-and-the-evolving-language-of-love/

emilia

I feel that too much blame is left at the publishers’ doors in this sort of debate, but the sad truth is that teachers and institutions are also complicit. Often authors and publishers *do* push the envelope, and are rewarded by poor sales.

I am reminded of an excellent series by Pearson, Impact Issues (by Richard Day, Joseph Shaules and Junko Yamanaka), which features excellent listening passages intended for discussion. In a previous edition it included a passage in which a young man talked about his gay parents, and another in which a young woman was considering an abortion, among other somewhat less contentious issues. It wasn’t heavy-handed at all, and in fact invited fair debate from all sides. Sadly, the next edition saw these two units replaced by others due to teachers complaining. I myself was present at a teachers’ meeting once where a fellow faculty member criticized adopting the title specifically because of those topics.

I’m no apologist for the industry by any means, but the fact is, there *are* less anodyne coursebooks out there. We don’t hear about them, however, because they don’t tend to have much of a shelf life.

Yes, Marcos, I think you have touched on a sad truth here. Who was it who said that – despite their left-wing pretensions – teachers as a whole are inherently conservative?

Well I voted for you in the debate because, how could I not (apart from your extraordinarily articulate performance etc etc!!). Many lives are NOT represented in materials. Yet the problem for coursebooks is that they get into all sorts of hands and (as I know to my cost) if you do something which you think is genuinely useful (in my case teaching vocabulary for reproduction and childbirth – surely language that is eminently useful for a huge percentage of would-be English speakers at some stage in their lives) your book ends up getting pulped (it happened) because the ‘wrong’ teachers tried to use it.

Lindsay is right – and so are some of the points you quote – or rather Catherine Walter did. We cannot represent the multitudinous different lives we confront. There’s not enough space on the page. We cannot know what lives to represent to whom until we have the ‘whom’ in front of us. It IS the teacher’s job to mould and interrogate the content so that it reflects something of the lives in the classroom – or maybe it would be better to have no coursebook at all!!! But that, as you said in the debate, is another issue altogether.

I think there ARE ways to make things better. I do think some of the consumerist stuff is overdone, ditto middle-class native speakerism etc. But the future (and the digital world) may change that.

Well done for winning the debate, though!

Jeremy

Thank you, Jeremy… and I would like to share your faith in the potential of the digital world to ‘liberate’ teachers and their learners from the kinds of strictures associated with print materials. But – as I watch the digital world becoming more and more the province of the ‘big players’ (Google, Amazon, P***son etc) I fear that educational publishing will become even more regimented, more restrictive, and more conservative, not less.

Very interesting. Thank you. I abstain since I see both arguments as dealing with perceptions of reality. The true nature of reality lies beyond the perception. Luan’s excellent suggestion of fantasy and fictional narrative with ‘overt moral lessons’ (above) has a better chance of representing reality than any teacher/student perception of it.

Mainstream coursebook publishing, as Marcos writes, has become a marketing exercise. Teachers get what the bulk of teachers ask for.

Thanks, Gareth. Yes, it’s as well to be reminded that there are layers upon layers of ‘reality’, and that maybe it’s too much to ask of language teaching materials that they engage with any layers beyond the most utilitarian and mundane. At the same time, wouldn’t it be amazing if someone were to write a language course that had the qualities of a self-improvement text or even a spiritual guide?!

Self-improvement books are blank pages and come with a pencil. But, ‘Heartway’ and ‘Inside In’ are courses I’ve always wanted to write 🙂

Hi Scott,

I am very much on your side regarding this debate, for many reasons. I think part of the problem is that this aspirational approach to materials-writing, which assumes everybody learning English wants to be rich and (more importantly) Western, has become out-of-step with the clientele that coursebooks cater for.

It may have been the case in the past that people learning English were doing so because they wanted to emulate/become closer to/make contact with people from English-speaking countries, and were therefore anglocentric and aspirational in that respect. However, times have changed; English is no longer the “property” of white native-speakers.

In non-native English speaking cultures people are mostly learning English to communicate with other non-native speakers, and Western middle-class cultural norms are largely irrelevant. There may be a regional variety of English that has developed out of a local culture and which is more useful for them to be learning. Such a context has no place for the Eurocentric references that exist in coursebooks.

Even in the UK where I work, many learners these days really struggle to identify with the ideals presented in coursebooks. A lot of their everyday use of English is with other non-native speakers, and the kinds of transactional language they need to use (following verbal instructions at work, visiting the job centre, filling in forms to apply for housing benefit, attending parents evenings for their kids, applying for a construction course in a college etc.) are largely ignored in coursebooks.

Obviously (and I’ve been going on about this for years) many of the problems with coursebooks stem from the fact that publishers are still intent on publishing a single product that they can market everywhere; the result is bound to be banal and rather meaningless. But the problem is compounded by this Gardneresque assumption that English learners are not only interested in British/Western culture, but also that they aspire to becoming part of it. Most English learners these days just don’t.

Thank you Steve – and can I urge followers of this blog to check out Steve’s – especially relevant is the post on ‘Parsnips’:

Thanks for the plug, Scott! Yes, my post (linked above) is relevant to this debate as it explores whether there is actually a responsibility to represent groups of society that are currently airbrushed out of global materials. I maintain that the problem exists because of the global corporate industry that ELT has become. Publishers control the materials we use, and they are always going to prioritise profit over pedagogy. Education should never be corporate, but in the case of ELT it is.

Like Lindsay, I also found myself agreeing with your arguments in the Liverpool debate despite being a materials writer trying hard to challenge the anodyne nature of ELT materials!

As you know, a coursebook unit of mine which did feature a gay couple was quickly “cleaned up” and turned into a straight one when the publisher decided to introduce the title to markets in which it would be considered unacceptable. It was argued, among other things that teachers would be uncomfortable dealing with such topics, an argument that came up in the debate as well.

Yet, there was actually no need for the teacher “to deal with the topic”, the couple were placed alongside three acceptable ones in short texts about they how met, a vehicle for the past progressive and past simple tenses more than anything else. I feel that incidental representation/visibility is enough here, there is no obligation to confront the issue or even discuss it in class just because it is there. As Lindsay also mentioned, such an approach runs the risk of being at best earnest and at worst patronizing, for example by “othering” the gay community. Depending on context and rapport, such a debate can emerge in class, it doesn’t need to be triggered by the coursebook.

As Marcos rightly says, other writers have attempted to do the same thing over the years but their books have either been sanitized like mine or sunk without trace. A sad reality. Congratulations, anyway, on putting that unit together. It is frighteningly representative. I’m glad to see my dog alongside the other aspirational status symbols there 😉

Far be it from you to mention Framework by name, Ben, but ten years on it’s interesting to reflect, a shade ruefully perhaps, how committed that project was to shaking up (if not subverting) “the cheery, sanitized, even anodyne, world of the coursebook”.

Also, your suggestion that “such a debate can emerge in class, it doesn’t need to be triggered by the coursebook”: true, of course, but is it not the case that such a debate can just as easily be triggered in class without a coursebook? And of course if the teacher is skillful enough to tease out relevant target language from the language which emerges during the debate, then the coursebook becomes almost entirely redundant. Not for a while yet though, let’s hope!

Great arguments, Scott. I take it the debate was filmed? Certainly hope so.

Yes, Mark, for better or worse, the debate was filmed – you’ll find the link in the original post at the end of the References section. I don’t claim it makes great viewing though!

Thanks, Ben – for this sad but revealing anecdote. (And thanks for ‘outing’ your dog!)

I agree that, in including non-mainstream content, there is a real danger of tokenism, overt PC-ness, and essentialism: the coursebook becomes like a reality show with one or two squeaky-clean gays and blacks included for good measure. I take heart from the changes that, even in my lifetime, I’ve witnessed in Hollywood movies, where gay, black, Asian etc characters (albeit not Muslim ones) are no longer walk-on stereotypes. Could the same kind of unobtrusive diversity occur in textbooks? To what extent does positive discrimination (in terms of representation) help or hinder this process? I mean, if educational publishers were required to be truly inclusive (in the way that they are with regards to women), would it make a difference? Or would it backfire?

Definitely makes a difference. As a Western Muslim teaching in Saudi Arabia, I raise my ‘veil’ to you for making that point Scott! In fact, an interesting point I have noticed since being here, is the surprise my students express when they find out I’m a Muslim. It’s as though the equations is as unlikely to them as it is to the publishers! Makes me feel rather special but also very determined to breakdown the stereotype. I sometimes get the sense that my students feel a degree of unease about their Islam (cultural and/or religious) in the classroom until they find out their teacher’s a Muslim. Clearly the portrayal of Muslims in the media has something to do with it, but wouldn’t the classroom be the ideal place to show them otherwise. I loved the anecdote about the pear told by the Korean guy in the debate, simple and totally representative of the point this whole debate was about. So, to answer your last question, no, why should it backfire?

Hi there,

Re which way I would vote, it probably goes without saying, as you cannot standardise the lives and needs of all students in any one given class, let alone world or nationwide, so… although the 4th point made by your ‘opponent’ makes reference to that (which in turn means that, curiously, your opponent supported the motion at that point).

I would like to comment on the other three points you quote, though, if that’s ok.

1. “Students don’t want to be reminded of their less than perfect lives:”

I don’t agree. I think students want to be able to CHOOSE whether their ‘less than perfect lives’ are to be discussed in class or not. We all have what I call ‘The Twilight Zone’, which may mean we don’t want to ‘Describe our family’ or house or whatever, but we may want to. We may want to avoid topics such as death, or we may want to discuss them. We may want to avoid discussing immigration because we are immigrants or because we are anti-immigration, or we may want to share our worries because we get on with our classmates, our teacher’s an immigrant too and…. etc.

I don’t think we, teachers or materials writers, should be making assumptions about what students do and don’t want to talk about – in order for them to personalise their learning in the sense of ‘making the language theirs’, they need to be the ones to decide how to use their new ‘tools’. I am supposed to use a coursebook, where I work. By following the students’ lead, I’ve used it… not at all in one class, as at least two of the students in the class found it offensive in its representation of gender roles, and twice in another class where we used the misrepresentations of life in the texts as the basis for our discussion. The coursebook is a ‘major international bestseller’ and my students are A1 and A2….. so there must be a lot of people out there making assumptions.

2. “The aspirational culture instantiated in coursebook images and texts…. represents the sort of ‘ideal self’ that some scholars (e.g. Dörnyei 2009) argue is the prerequisite for success in second language learning.”

Again, based on what I see from my own students, while the Dörnyei quotation is applicable, it is not applicable in a way that would oppose your motion. I work in Spain, my students are all adults (18-63, as far as I remember) and virtually ALL of them are unemployed. Apart from the retired ones. Some are younger and have not worked yet, some are older and have been made redundant. Their ‘ideal self’ is not a Ferrari-driving, heterosexual, tablet owning, married-with-two-kids sort of self; it’s what they hope is their ‘Future Self’, in line with Dörnyei’s concept (and Jane Arnold’s).

This Future Self has far more to do with being accepted as an immigrant or being able to emigrate, getting a job as a nurse / mental health care worker / architect / teacher, paying the bills, falling in love (or at least, um, practising), losing weight etc etc than with owning things or having a budget that allows you to eat all food groups in the correct proportion according to the ‘food pyramid’ or live/work in a green building with a garden on the roof. And they want to talk about their REAL aspirations far more than about their shopping habits.

3.” All learning involves first identifying (proto-)typical examples of a behaviour, and only later accommodating more marginal phenomena. Hence the need to start with exemplars of the ‘norm’: e.g. white, middle-class, heterosexual family structures, before engaging with the ‘exceptions’.”

All learning? The ‘norm’? Pardon? This sounds like ‘how to learn you’re weird: first identify the norm, then realise you’re not it’. Again, in one class alone, I have four students over 45 (the women have tinted hair, not immaculately coiffed, perfectly conditioned white bobs), I have obsese students, immigrants, homosexuals, heterosexuals with dysmorphia issues, I have male dance teachers who work evenings only, nurses who work on the nightshift, 90% unemployed, retired people, divorced people, single parents, students who smoke (!), single thirtysomethings ……. I’m struggling to think of a single student that would fit a ‘norm’. Even the pretty girls either wear glasses or are sometimes bad-tempered, and ‘white’ is a relative concept in Spain … The only student who doesn’t mention her ‘issue’ is the seriously obese one, but all the rest want to use their new language to apply it to THEIR circumstances, themselves, to talk about their lives, loves and worries, rather than some invented ‘norm’. A simple example from an A1 class practising there is/are the other day. They all brought in photos they’d taken to play Kim’s Game. My unemployed architect’s photos had set squares and compasses and things in it, a middle-aged woman had wrinkle cream, paracetamol…., a male nurse had lip balm and sticky plasters… the pencil sharpeners and dictionaries of the coursebook images were, hey, not there. Not relevant to ‘normal’ students.

Emotional response and personalising are far weightier than indifference, when it comes to motivation and learning stimuli. I’m completely sure.

Sorry for occupying your comments thread!!

Best

Fiona

Thanks Fiona, for your eloquence and passion! I won’t address all your points (some of them have been/will be addressed elsewhere) but only this:

“I don’t think we, teachers or materials writers, should be making assumptions about what students do and don’t want to talk about”.

And yet this seems to be the way that (ELT) publishing works: as I argued in the debate – the ‘end user’ (i.e. the learner) is never consulted. The buck seems to stop at the teachers, or heads of department, or even ministry officials, in terms of what will interest/engage/motivate the students. I cited a recent e-publication directed at aspiring ELT writers, which made no mention of the learners in the consultation process.

In the pub after the debate, an eminent (ex-)coursebook writer denied this hotly, and said that when he used to write coursebooks the students were endlessly polled. He admitted that they mostly wanted to talk about music and sport, with a male bias towards the latter.

Hi Scott,

Interesting discussion and thanks for the link to your debate.

Just on the point of illustrations, I often wonder why student coursebooks need them anyway, they are a big waste of space and after all they aren’t considered necessary in ELT books on, say, teaching or methodology. If visuals are essential for teaching a specific language point, students can bring them to class.

One problem with ELT coursebooks is that there are now far too many of them and this saturated ‘global’ industry is often aimed at ENSP (English for No Specific Purpose). So there is a constant casting around for interesting new topics, issues of the day, but avoiding risk and anything that might damage market share. So ultimately that anodyne, Sunday supplement lifestyle look.

Actually, representation in the multitude of books and associated materials produced for the BE/ESP market doesn’t fare much better. The business men in suits, business women in suits, construction workers in hard hats, and doctors in white coats, are from the same modelling agencies as the smiling lifestyle people having barbecues. Again, I find it much more interesting to ask students to present relevant, real-life examples.

Interesting point about the need (or not) for illustrations. I do think that illustrations can be useful, not only for illustrating the meaning of vocabulary items, but as a means of contextualizing language, generating interest, activating schema, and providing prompts for language production (as in my mock-up). But I also think that quite a lot of design matter is simply that: matter. Page-filler- Nevertheless, it can be usefully exploited, in terms of the (covert) messages it is conveying.

From Tessa Woodward (who had trouble uploading this, so she sent me an email):

Dear Scott and Catherine,

I was lucky enough to attend the ELTJ debate and enjoyed the witty and generous way in which both of you conducted yourselves. Thanks for the thoughts and the fun.

Some years ago I ran a workshop for MATSDA entitled ‘Let there be you. Let there be me: Gender balance in ELT materials’ (See pp 13-14 in Folio the journal of MATSDA. Vol. 8. 1 /2 November 2003 for the write up)

In the workshop, a group of us looked at a load of ELT course books and other teaching and learning materials. Several people predicted that, it being the start of the 21st century, there would be plenty of women represented in them. We counted and then coded the representations of women and girls in the material. Even those participants who had been most sure at the start of the workshop that there would be fairness were actually appalled at the low ratios of women represented and the types of representation given.

Here we are in 2013 now. Any better? Gosh I hope so! But having looked casually at a few new books in the exhibition hall, I know there is still work to be done.

We hold up half the sky. We need to see loads of us in the books too.

Thanks for the chance to put a view.

Tessa

Scott, I’m glad this topic is being thought about and should be constantly held up in the light, in front of our eyes. Critical pedagogy is in the decline and we need improved binoculars.

I support your arguments and do think reality is not shown in textbooks even though technology now allows this to be so easy and so possible. Marketing men rule and just like we’d never find “reality” in Vogue or in Esquire we won’t find it in a textbook. So I think you should have went further in your argument. The reasons are not just ideological (and I like Eric bringing Geertz into the conversation – he’d have shown how the “signs” within the textbook are just ways of controlling the cultural conversation that happens) not just idealogical but profit driven (and maybe profit/corporatism is an ideology and that is what you mean?)

We are all part of a system. ELT textbooks aren’t just selling how well they’ll help teacher and students learn English. More importantly they are selling “a dream”. They are a big form of advertising and to quote Illich – “School is the advertising agency which makes you believe that you need the society as it is.” In ELT, even worse given how there are few governmental or regulatory filters for curriculum design and content that gets to our classrooms. I’ll also take a moment to quote McCluhan who knew more about this topic than most ” Anyone who tries to make a distinction between education and entertainment doesn’t know the first thing about either.” A point to be made that we are amusing students – why would they want to look at their own dreary world or self? The problem is a lot bigger than just what images and topics appear in textbooks, it is a problem of power and who controls what is ultimately served up on the language learners dinner table.

The crux is that textbooks are a consumer product. What you see in them are at the end of the day what will sell (and Steve’s point about selling everywhere is noted). The corporate mindset controls the pedagogical one.

What I find sad is that when I’ve done an activity in textbook deconstruction / analysis in a curriculum development course, students, so very few ever can wipe their eyes clean and see how corporate driven the images are and language is. We can’t see the ghost inside the machine ….

The only solution is for a teacher is to allow students to create the materials from which classroom activity and study will be based. Go bottom up.

David

Thanks for your comment, David. You ask ‘maybe profit/corporatism is an ideology and that is what you mean?’ – yes, that is indeed what I mean, and I have blogged about it before, here: N is for Neoliberalism.

Go bottom up. Yes. I couldn’t agree more.

Good evening!

The truth lies somewhere in the middle.. in the fact the Greek ELT market is targeted at the needs of the various Exam Boards promoting the content and the pass ratio of their exams, so they orient themselves to meet THEIR needs rather than the real needs of Greek ELT learners struggling to survive the hardships of the financial banking collapse in Southern Europe (Greece, Cyprus, Italy, Portugal and Spain)…

Nevertheless, in class, we take seriously into account this phenomenon and try to implement ElT content that reflects their real needs (you see it from the look on their faces- THEY ASK ME TO DO SO), in class, when it comes to have either a Speaking or Writing session, where their background knowledge combined with the TL input they receive in class will transform into a productive spoken or written output.. (Miss, why do you ask us about Environmental Protection or Recycling, the moment when we have no more rubbish left to throw in the bin?- We have no leftovers..we eat it all..nothing is wasted..- when we did recycling the other day…)

Thank you for the space allowed to me for expressing my viewpoint..

Thanks for posting this summary Scott. I wasn’t able to make it to IATEFL this year, but I’d been planning to watch the debate online when I get a chance.

Funny as I was discussing the same thing this week on a friend’s blog. I think it’s worth remembering that although coursebooks do (and have to to a large extent) appeal to homogenous, western, aspirational ideals, the fact that this produces such large revenues means that they are able to do some pretty amazing things, too – there are some excellent materials out there which less experienced teachers can learn a lot from.

At the same time it’s great to hear the likes of Lindsay, Jeremy and Ben doing what they can, even if these do get knocked back and streamlined for certain markets. I remember about 10 years ago using a resource book called ‘Taboos and Issues’ (Richard MacAndrew and Ron Martinez – it’s fairly well-known, I think). Lots of controversial issues discussed and dealt with sensitively, within the material itself. I wonder if this is a useful role for these types of themes i.e. as supplementary material. But then what also worries me is that as soon as you make such a division, it could be as if you are saying these issues are less important.

Willy Cardoso touches on heteronormativity in his assessment of a coursebook as part of his Master’s. It’s very interesting but he hasn’t gone into much detail in it on his blog: http://bit.ly/zKVLdS. A very interesting issue I think, which I’d like to see discussed more.

Anyway, thanks again for starting this debate.

Damian

Thanks, Damian. Regarding the issue of ‘heteronormativity’ (a great word to drop into a conversation by the way) has been around for a bit (although not necessarily under that guise). I wrote about it a while back in an article that you can access here: Window-dressing vs cross-dressing in the ELT subculture.

As the writer of coursebooks that were very much spurred into being by similar frustrations to the kind you voice above, and who has, I’d like to believe, covered at least a meaty chunk of the areas that, as you point out, are often whitewashed from ELT coursebooks – bribery and corruption, money problems, the housing crisis, swearing, and so on – I have to note a certain irony in the fact that in a talk (Liverpool IATEFL) – and in this post – on representation, you’re somewhat guilty yourself of misrepresenting the full reality – and diversity – of coursebooks out there.

Whilst the points you make may well have held some considerable amount of water back in 2000, I think things have moved on in publishing, and over recent years books like my own INNOVATIONS and OUTCOMES, as well as Lindsay’s work with GLOBAL, Ben Goldstein’s work for Richmond and others. have all challenged the status quo and have tackled many of the areas – and lexical areas – you claim are absent. Some kind of further acknowledgement of these advances from the Dogme crowd wouldn’t go unappreciated.

On top of that, though, there’s a whole slew of further questions and complications. Partly there’s the issue of whether anything other than ourselves are able to really represent ourselves. How would it be possible for any kind of content whatsoever to ‘represent’ the lives and interests of even eight to ten people in a class? We would all need whole books – or movies – if our true selves are to be ‘represented’ in any kind of fullness.

Ultimately, of course, we all represent ourselves in our own ways – and in different ways at different times. Given this, actually, even the trite and parodied material you offer up above does of course provide the opportunity for a gay, unemployed young Spaniard living on hos folks’ couch to answer these three questions in bubbles however the hell he wants in class during the practice of that language. The fact that these options aren’t mentioned in the published materials themselves doesn’t, of course, preclude the possibility of the material facilitating the representation of a whole range of options from the students themselves.

If what you’re arguing for is simply representation of a wider range of lifestyle choices, sexual orientation, etc then of course one would be mad to disagree that it’d be nice to see at least a gay couple or a Kurd or whatever in ELT material.

That said, I do also sometimes wonder if the interest in marginality that swirls around in ELT discussions of this type is at least partially a reflection of the fact that we ELT folk are marginal ourselves in some deep and fundamental way, perhaps even more so for those that are gay. I remain deeply sceptical of the idea that most students – or, sadly, teachers really actually want much more shade and complexity in their material.

To give but one example, in INNOVATIONS Pre-Int, we have a conversation that we felt leaves the possibility of two characters in it being gay or bi or somehow leading a double-life and managed to sneak this past our editors. The idea was that if you cannot reference these issues directly, then at least you can leave the space and option for interested teachers – and students to – raise them in class. We have a question asking what students think the relationship between these two characters is and term after term after term, I asked, thinking eventually someone would point out that they could be gay, but no-one ever did. I even ended up mentioning it myself sometimes, to general bewilderment, but it NEVER came from the class.

Perhaps the vast majority of students are far less interested in the issues you are, and actually more interested in bland consumerist neo-liberal agendas than we give them . . . um . . . ‘credit’ for!

Finally, in case anyone out there hasn’t seen it already, I did a recent post on the whole issue of taboos and publishing and teaching, which kind of dovetails with this issue. It’s here:

Really interesting post – Thanks for sharing, Hugh.

Thanks, Hugh, for your comment. (I couldn’t help noticing you leave the debate precipitately. I assume you had a bus to catch. Or an axe to grind. 😉 )

You say: “If what you’re arguing for is simply representation of a wider range of lifestyle choices, sexual orientation, etc then of course one would be mad to disagree that it’d be nice to see at least a gay couple or a Kurd or whatever in ELT material”.

Yes, exactly. I think there’s a risk of two issues getting confused: one is the way learners etc are represented, not represented, or misrepresented, in coursebook images and texts, and the other is the merits (or not) of including ‘taboo’ content – the famous PARSNIPs. Obviously, the two discussions overlap, but I wasn’t necessarily arguing for more ‘edge’, just more realism. (That was the brief for the debate, anyway).

That said, I have argued (elsewhere) for the inclusion of more challenging content. But, as you say:

Even if this were true (and you may be right in the case of many learners), don’t we have some responsibility, as educators, in asserting such values as social justice, equality, freedom of speech, etc? (Even at the risk of being branded as proselytizers, indoctrinators, etc)

Interesting article

There was once a Kurd in Advanced E File, a guy working in a chip shop in London claimed to come from Kurdistan in a listening text. My Turkish students became very agitated having been informed by the govt, throughout their lives, that Kurdistan does not exist.

Oxford were informed on the spot and I believe the offending person was removed from the book.

representation is quite a minefield especially when publishing houses risk sales…….

In one sense, it’s a little bit unfair to criticise coursebooks for not being all things to all people, which as you said yourself Scott at the beginning of your talk, is obviously not possible. Furthermore, even when authors are given freedom to venture outside the bland, anodyne and aspirational world that many coursebooks are perceived to live in, there seems to be every chance that they end up in the situation that Jeremy and Marcos described above. That is, they are either used badly or not at all. So, it’s hard to blame publishers (like Ben’s) for sticking to safe ground and removing all possible traces of offence.

However, that’s not to let coursebook publishers of the hook and think that they couldn’t do better. Despite one or two examples that Catherine gave, it’s seems that locally produced coursebooks are the exception rather than the rule, especially where adult coursebooks are concerned. Even when there are special editions for different countries, this seems to be done more on grounds of censorship (as in Ben’s example) rather than with reference to local needs and interests.

When it comes to language, the story seems to be the same. If students are lucky, they may have some lexis and instructions translated into L1 but it appears that little thought is given beyond that.

So whilst coursebooks will of course never satisfy everyone, they could at least take local contexts into account a bit more. After all, if teachers are teaching Business English, they use a Business English textbook which is relevant to business contexts. If teachers are preparing students for exams, they use an exam textbook, which helps students answer particular types of exam questions. Surely, it’s not that hard to produce coursebooks that reflect local culture and language?

Thanks, Peter. The case for ‘localizing’ materials would seem to find support in the view expressed by Pennycook in a recent book (Language as a Local Practice, Routledge 2010) that all language practice emerges out of local social practices. ‘Everything happens locally. However global a practice may be, it still always happens locally…. Looking at language as a local practice implies that language is part of social and local activity, and both locality and language emerge from the activities engaged in’ (p. 128).

This suggests (to me, at least) that the learning of a language needs to be construed as a localized, social practice, and that using a language means re-localizing it. Pennycook cites Claire Kramsch’s notion of a ‘traffic in meaning’ as being ‘precisely what language teaching should be about, so that language competence should be measured not as the capacity to perform in one language in a specific domain, but rather as “the ability to translate, transpose and critically reflect on social, cultural and historical meanings conveyed by the grammar and lexicon”…. When we learn a language, we enter the traffic….’ (p. 141).

When we enter the traffic, we do it locally, and wherever we stop, it will always be local. Hence, the need for localizing language practices – and localized texts.

Is it not the teacher’s role (to a great degree, at least) to localize the language learning process?

What would publishers truly gain by localizing textbooks? I would assume that all “big players” (including the likes of P***son) investigate any possible avenue that would lead toward higher sales and…a higher profit margin; however, textbooks remain largely “universally applicable”…

I agree that localized texts could potentially be extremely successful in engaging the students and addressing their language needs more closely (not to mention less adaptation work for the teacher). But as long as the big profit remains in a “one-version-for-all,” the option of localized texts will never exist.

If the needs of students and publishers occasionally coincide, it is entirely fortuitous. Teachers’ needs are often far more important to publishers than those of students. Or so it seems to me.

Language is a vehicle for what? For the expression of whatever the user wishes to communicate. Why should anyone other than the learner determine the context (the theme) of that communication?

As Peter indicates, this issue is more likely to affect materials written for adults. Course books for state schools usually need the approval of the educational ministry (or ministries). I have some experience in writing materials for German secondary school books, where authors, editors and advisors bend over backwards to get things right. This entails, among other things, meeting the curriculum requirements of the various federal states, which means that the publishers have to decide whether to produce a one-size-fits-all book for the whole of Germany, or tailored versions for each state. Bavaria, for example, has a relatively conservative curriculum, and North Rhine-Westphalia a more ‘progressive’ one.

This reminds me of a text I once wrote long ago for a course book unit (Year 6, i.e. eleven-year-olds), where I had a grandmother baking a chocolate cake for her two grandchildren in order to introduce the will-future with ‘if’. To stop the children squabbling over who should cut the cake (“If Mark cuts the cake, he’ll take the biggest slice”), the grandmother allows one child to cut the cake and the other to choose the slice. Problem solved! During a meeting to discuss the unit, the advisor from North Rhine-Westphalia accused me of stereotyping the grandmother by having her ‘stuck at home’ baking cakes. Far better, he thought, to have modern granny who goes to work and would rather go bungee jumping than slave in the kitchen! The Bavarian advisor disagreed. Grandmothers still bake cakes and anyway children prefer (or should be given) ‘traditional’ role models. An advisor from a former East German communist state concurred. After the ding-dong had died down, I wearily agreed to rewrite the text. It wasn’t in my power to turn Grandma Penrose into Grandpa Penrose, so I gritted my teeth and set the story in a fast-food restaurant in a shopping centre with the children squabbling over slices of pizza instead. I could live with that. But no doubt someone somewhere is outraged about how the two children are depicted guzzling neo-liberalist fast food, and that publishers are to blame for childhood obesity. At the same time, I agree with Scott, the NRW adviser and others on this thread that it’s important to question one’s assumptions about what readers will relate to.

Maybe others on this thread can tell us more about the course books used in secondary schools in their countries – are they locally produced or imported? How much power do educational ministries have over what goes into them?

“This reminds me of a text I once wrote long ago for a course book unit… ”

Thanks, Stephanie – in conversations with other materials writers this kind of story comes up again and again. Even after the debate, an eminent writer of grammar books (who had argued vociferously that there is no censorship in ELT materials) confessed to me that he had had to change a number of fairly innocuous example sentences because they would not go down well in Japan.

My brother-in-law learnt English at school with a series of coursebooks that had lovely little texts about things like the opening ceremony of the New Town Stadium (attended by members of the executive Council, officers of the Yugoslav People’s Army and representatives of the mass organisations), the rich variety of Yugoslav exports, and the existence of spittoons in London barber shops. Many years later, he spits at the mention of Yugoslavia … which just goes to prove how powerfully coursebooks can influence young school kids.

The series, by the way, is called Angleska Vadnica (published in 1966). I know you have other gems like these in your collection: how much did they influence their users, I wonder.

I knew that your next stimulating post would be up, Scott, before I had a chance to fully digest the previous ones:)

YES, “the cheery, sanitized, even anodyne, world of the coursebook” needs to be addressed and criticized. Learning should be linked to the learners’ worlds and social realities.

[Start of sidekick] This should include the learners’ world of English communication with native speakers – yes – but more often than not, and for critical communicative purposes, they communicate with other non-native speakers(!) of English. Do I read the magic word? Is there a serious space for serious ELF in ELT? (SteveBrown70 got close to it) [End of sidekick]

Considering the diversity among students in most classroom, however, it is difficult to see how a coursebook could represent a matching range of opportunities for authentication. But then, a coursebook can and should be seen as a launching pad for learning activities that reach out beyond the coursebook’s own narrow range. The slickness of the false glamour can, for instance, be questioned; alternative lifes can be explored. Even a bad coursebook can be used (by a good teacher) to facilitate good learning. False glamour might even be more helpful for differentiated authentification than a unit highlighting a social hotspot. Good coursebooks, however, should be designed to actively facilitate ‘reaching out’ activities; they would integrate ideas and material for branching out into individual authentication activities. Reaching out beyond the coursebooks – and the classroom, for that matter – should be a key objective. And why nor creatively exploit the pedagogical potential of web2 based e-learning to support explorations for collaborative diversifed authentication.

Thanks for your comment, Kurt. It was Widdowson, of course, who suggested that any material – authentic or not – could be ‘authenticated’ by the learner, if they saw that it was congruent with their learning needs. This perhaps relates to Luiz’s comment (below) that he remembers certain texts as being engaging, even though (as a teacher of those same texts) I remember them as requiring a lot of my own effort to make work. In the end, perhaps, there is no magic formula that will guarantee that one text will engage the learners while another may not. In fact, if you polled a sample of learners, they would probably be surprised that the kinds of texts in second language textbooks should even pretend to be engaging! They might reasonably argue that that is not their point.

Scott, your post evokes memories of John Berger’s “Ways of Seeing” (1972), a four-part BBC series about cultural representations, particularly in visual images, later published as a book. The series and book are available online, as far as I know. It’s interesting to note how relevant Berger’s criticisms are today, nearly a half century later, even if we might now expand upon them a bit.

I don’t remember if Berger explicitly mentions the idea of imitating one’s oppressor, but Freire certainly does in “Pedagogy of Oppression” (1970). And I think both those who claim to defend and support the oppressed, as well as those who question whether such oppression exists, should seek out authentic voices to help us formulate our opinions. Self disclosure: I write this on one of my many Apple devices, after a massage session, in my oversized home, stocked with more than I really need, situated within the liberal bastion of Portlandia. That being said, I press on… 😉

Imitating one’s oppressor can be identified as a form of relief from oppression; it’s easier to give in to the status quo than to challenge and attempt to change it. I can well imagine myself going with the flow rather than facing constant harassment, discrimination, and the aforementioned “othering”, however covert it might be. I know I’ve buried my head in the sand and bitten my tongue more than once, out of convenience, fear, or even opportunism.

Is a debate a mild form of “othering” insofar as it polarizes people and plays on our dualistic notions of right/wrong, good/bad, them/us? I’m not sure.

I am sure that I haven’t used course books in the classroom for nearly a decade, so I’m neither well qualified to provide Hugh with any ‘further acknowledgement’, nor to judge the plausibility of the course book page you’ve replicated.

My lack of current exposure to course book representation does not, however, prevent representations like the ones you’ve called into question from making their way into the classroom I share with language learners; we live in the world of images and carry on inner dialogues, just as you and the rest are doing this very moment.

And that brings me to what I consider the crux of your post and the comments I’ve read so far:

Does matter precede thought (the philosophy of materialism?), so that altering cultural representations will, if ever so gradually, change hearts and minds? I don’t see much evidence of it. I see more promise in art, constructive dialogue, and exposure to different points of view from thoughtful people with good intentions, which is why I’d like to thank you and everyone who’s commented thus far.

Best,

Rob

“Does matter precede thought (the philosophy of materialism?), so that altering cultural representations will, if ever so gradually, change hearts and minds?”

Let me throw this back to you, Rob: how do you account for the fact that there has been a huge swing in public opinion in the US in favor of same-sex marriage in just half a dozen years? This can’t be purely demographic. How much has the conspicuous role of gay characters in TV sitcoms, such as Will and Grace and Modern Family, had to do with it, I wonder? And how much does the presence of gay characters in TV sitcoms owe, in turn, to the painfully-slow increase in visibility of sympathetic gay characters in Hollywood movies? Ergo, altering cultural representations might – just might – change hearts and minds.

Is it too much to hope that a similar shift in opinion could be achieved if there were jolly nice Muslims in sit-coms?

Hope I’m not stealing your thunder here, Rob, but I feel I need to add my two cents to this one:

Although I do not own or ever watch TV, I am aware of the increasing emergence of gay characters in TV shows and in feature films. I think this is more a *result* of the shift in public opinion on homosexuality than a *cause* of the shift. Corporations know their customers well and market what is marketable – hence the ever-increasing presence of broken and “patch-work” families both on TV and in films. People enjoy entertainment more when they can identify with the characters. With the rapid growth of divorce and gay marriage comes the equally rapid growth of easily marketable entertainment.

That given, could the ESOL textbook industry possibly find topics, characters etc. that would allow a diverse body of learners to identify with those topics and thereby increase their language learning potential?

“altering cultural representations might – just might – change hearts and minds”

Is this the role of an ESOL textbook?

In some parts of the world homosexuality, for example, is not only considered completely unacceptable, it is illegal. How would U.S. teachers feel about a chapter in an ESL book on a cancer patient using medical marijuana? Would that even be legally admissible in schools?

I don’t completely agree that mass media follows what the majority of the audience wants. I recall the famous sitcom episode from “All in the Family” in 1971, where the main character, Archie Bunker, was confronted with his prejudices about homosexuality. For sure, at that time most straight Americans were clueless on this issue. It transformed many people’s attitudes.

As for your point about whether it is our role as EFL or ESOL teachers to open our students’ minds to new ideas, or whether the course materials should include topics that might make some people feel uncomfortable, we all have freedom of choice about what to use in our classes and what to skip, assuming our teaching situation allows for that. I feel very grateful that mine does. The day I have to fit myself into a bland curriculum (or bring a gun to class) is the day I quit.

“Let me throw this back to you, Rob: how do you account for the fact that there has been a huge swing in public opinion in the US in favor of same-sex marriage in just half a dozen years? This can’t be purely demographic.”

That very example came to mind as I typed the words you’ve excerpted above, Scott. If not purely demographic, it seems the shift in attitudes is largely so, as illustrated here:

http://www.people-press.org/2013/03/20/growing-support-for-gay-marriage-changed-minds-and-changing-demographics/

Now, why are so-called Millenials (born 1981 and later) more accepting of same-sex marriage? It could well be that Ellen’s coming out, Will & Grace (despite its controversial portrayal of gay men), et al. have helped pave the way for Modern Family (apparently one of Obama’s favorite sit-coms) as well as the changing attitudes among Millenials, and others in society. But look at this timeline:

http://www.factmonster.com/entertainment/gays-in-pop-culture-timeline.html

It’s been an evolution, and I’m not sure how much the types of representation you’ve cited has had to do with it although it’s undeniable that celebrity sells. Still, the Right is regrouping, and Republican attitudes have hardly shifted at all though the Log Cabin group persists.

I guarantee you there are plenty of homophobes left to make it difficult for same-sex marriage to become Federal law in the U.S., but we’ll soon find out how the courts rule on DOMA and Hollingsworth v. Perry.

In a nutshell, you might be right, Scott. Or, you should spend more time in the Midwestern and Southern United States. 🙂

Rob

Thanks Rob. I was intrigued to see this (on the Timeline):

Twenty years later, such a scene has yet to appear in an EFL coursebook. On the other hand, as Luiz suggests below, would it really be a breakthrough? (“What good would it ultimately do to include a gay couple in lesson 4 if their dialog still revolves around a shopping list + some and any?”)

I can’t help but wonder whether a more “inclusive” approach to textbook design would actually help to enhance student learning and, if so, to what extent. Insofar as we believe that textbooks have a role to play in students’ language development, I think the next logical question is: how exactly can they help? What does a good (good in the sense of being more conducive to learning) textbook look like? To me, the three key words are (1)clear, (2)reliable and (3)memorable. The Headway phenomenon has contributed decisively to (1) and (2), I think, but since the late 80s, we seem to be writing / selecting content that’s less and less memorable.

I used the Strategies series + a Guy Wellman classic (Longman Advanced English, I think) as a learner of English in the 80s. Thirty years later, I can still recall whole conversations, line by line, word by word, not because I identified culturally / ethnically / socially with the characters, but because the dialogs were either emotionally charged (e.g.: couple fighting and friend trying to intervene) or delightfully idiosyncratic (e.g.: right-wing senator who turned out to be an android).

For some reason, we seem to have shied away from content that is emotionally rich or genuinely funny. I think we’re writing books that are more complete (syllabuswise), more cohesive, glossier and generally more appealing than anything that ever saw the light of day in the 70s, 80s and perhaps even early 90s. But the centrality of grammar brought about by the Headway advent in 1987 seems to have brought with it a certain degree of risk aversion and blandness of content that we can’t seem to break away from. This, to be honest, bothers me more than the admittedly white, heteronormative, right-wing bias of most existing titles.

So what good would it ultimately do to include a gay couple in lesson 4 if their dialog still revolves around a shopping list + some and any?

Even if we pluck up the courage and somehow manage to garner enough editorial support to make our coursebooks (by the way, I’m an author myself) less white, less straight, less neo-liberal, we might still fail to humanize our content and wind up with the very same sort of “semi-skimmed” books that we’re complaining about.

Thanks for that thoughtful comment, Luiz. I think you’re right – that the insistent grammar focus post-1986 has leached (many) coursebooks of their originality, although, I have to say, if you go back a few years you find texts of a mind-numbing banality: I used some examples in the debate, such as this one (from Hornby 1954):

One thing we can be sure of is that Mr West is not going to rip Mrs West’s bodice off.

Although I agree with the first argument offered by your opponent (students not wanting to be reminded of their difficult realities), I think we are not doing them a favor by avoiding language they’ll need to talk about their reality. How would I feel as a learner if challenging real life issues aren’t brought up? What am I supposed to communicate about, what I wish were true?

Second, I take issue with the third argument about ‘norms’ and ‘exceptions’. While I understand that it would be hard to market a book in which there is reference to gays and lesbians, again, this is life -not an exception or abnormality. In the case of my LGBT students, why is it fair that there is zero representation of who they are in the textbooks we use? Learning a language is not just about grammar and vocabulary, it’s about learning to express our views and our opinions, even when they are controversial. It’s about learning how to appropriately disagree and interact with others and how to ask questions when you don’t understand why people act a certain way. I’d like to see more textbooks do that.

I’m not too convinced about the motivational charge of the ‘ideal self.’ I don’t have any data to back this claim (I wish!), but I bet its easier to actually feel a bigger distance to the language being learned when you can’t relate to the images and content. While I agree with the last statement and do think it’s our job as teachers to personalize a textbook’s content and make it relevant to our context, I also wish textbooks fostered more critical thinking and more opportunities for students to ask questions about the topics/content they are exposed to.