“O, swear not by the moon, the inconstant moon,

That monthly changes in her circled orb,

Lest that thy love prove likewise variable.”(Romeo & Juliet)

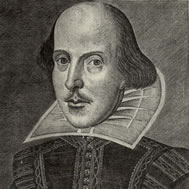

I have Shakespeare on the brain at the moment, having splashed out on tickets for three of the five shows that the Royal Shakespeare Company is putting on in New York this summer.

And, just by chance, I came across a fascinating book on Shakespeare’s grammar, first published in 1870, which details not only the differences between Elizabethan and modern grammar, but also documents – even celebrates – the enormous variability in the former. As the author, E.A. Abbott notes, in Elizabethan English, at least on a superficial view, “any irregularities whatever, whether in the formation of words or in the combination of words into sentences, are allowable” (Abbott, 1870, 1966, p. 5).

He proceeds to itemise some of the inconsistencies of Shakespeare’s grammar: “Every variety of apparent grammatical inaccuracy meets us. He for him, him for he; spoke and took, for spoken and taken; plural nominatives with singular verbs; relatives omitted where they are now considered necessary; … double negatives; double comparatives (‘more better,’ &c.) and superlatives; … and lastly, some verbs apparently with two nominatives, and others without any nominative at all” (p. 6).

As examples of how this variability manifests itself even within the same sentence, consider the following:

None are so surely caught when they are catch’d (Love‘s Labour Lost)

Where is thy husband now? Where be thy brothers? Where are thy children? (Richard III)

If thou beest not immortal, look about you (Julius Caesar)

I never loved you much; but I ha’ prais’d ye (Anthony and Cleopatra)

Makes both my body pine and soul to languish (Pericles)

Is there not wars? Is there not employment? (2 Henry IV)

Of course, we can attribute a lot of Shakespeare’s ‘errors’ to the requirements of prosody or to the negligence of typesetters. But many more may be due to what Abbott calls “the unfixed nature of the language”: “It must be remembered that the Elizabethan was a transitional period in the history of the English language” (p. 6). Hence the seemingly free variation between is and be, between thou forms and you forms, and between ye and you. Likewise, do-questions freeely alternate with verb inversion:

Countess. Do you love my son?

Helena. Your pardon, noble mistress!

Countess. Love you my son?

Helena. Do not you love him, madam?(All’s Well That Ends Well)

Elizabethan English was clearly in a state of flux, but is English any less variable now than it was in Shakespeare’s time, I wonder? Think of the way adjective + -er comparatives are yielding to more + adjective forms (see this comment on a previous post), or of the way past conditionals are mutating (which I wrote about here), or of the way I’m loving it is just the tip of an iceberg whereby stative verbs are becoming dynamic (mentioned in passing here). Think of the way the present perfect/past simple distinction has become elided in some registers of American English (Did you have breakfast yet?) or how like has become an all-purpose quotative (He’s like ‘Who, me?’) or how going forward has become a marker of futurity.

That variation is a fact of linguistic life has long been recognised by sociolinguists. As William Labov wrote, as long ago as 1969:

“One of the fundamental principles of sociolinguistic investigation might simply be stated as There are no single-style speakers. By this we mean that every speaker will show some variation in phonological and syntactic rules according to the immediate context in which he is speaking” (1969, 2003, p. 234).

More recently, as seen through the lens of complex systems theory, all language use – whether the language of a social group or the language of an individual – is subject to constant variation. “A language is not a fixed system. It varies in usage over speakers, places, and time” (Ellis, 2009, p. 139). Shakespeare’s language was probably no more nor less variable than that of an English speaker today. As Diane Larsen-Freeman (2010, p. 53) puts it: “From a Complexity Theory perspective, flux is an integral part of any system. It is not as though there was some uniform norm from which individuals deviate. Variability stems from the ongoing self-organization of systems of activity”. In other words, variability, both at the level of the social group or at the level of the individual, is not ‘noise’ or ‘error’, but is in integral part of the system as it evolves and adapts.

If language is in a constant state of flux, and if there is no such thing as ‘deviation from the norm’ – that is to say, if there is no error, as traditionally conceived – where does that leave us, as course designers, language teachers, and language testers? Put another way, how do we align the inherent variability of the learner’s emergent system with the inherent variability of the way that the language is being used by its speakers? If language is like “the inconstant moon/that monthly changes in her circled orb”, how do we get the measure of it?

If language is in a constant state of flux, and if there is no such thing as ‘deviation from the norm’ – that is to say, if there is no error, as traditionally conceived – where does that leave us, as course designers, language teachers, and language testers? Put another way, how do we align the inherent variability of the learner’s emergent system with the inherent variability of the way that the language is being used by its speakers? If language is like “the inconstant moon/that monthly changes in her circled orb”, how do we get the measure of it?

In attempting to provide a direction, Larsen-Freeman (2010, p. 53) is instructive:

“We need to take into account learners’ histories, orientations and intentions, thoughts and feelings. We need to consider the tasks that learners perform and to consider each performance anew — stable and predictable in part, but at the same time, variable, flexible, and dynamically adapted to fit the changing situation. Learners actively transform their linguistic world; they do not just conform to it”.

References:

Abbot, E.A. 1870. A Shakespearean Grammar: An attempt to illustrate some of the differences between Elizabethan and Modern English. London: Macmillan, re-published in 1966 by Dover Publications, New York.

Ellis, N. 2009. ‘Optimizing the input: frequency and sampling in usage-based and form-focused learning.’ In Long, M. & Doughty, C. (eds.) The Handbook of Language Teaching. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Labov, W. 1969. ‘Some sociolinguistic principles’. Reprinted in Paulston, C.B., & Tucker, G.R. (eds.) (2003) Sociolinguistics: The Essential Readings. Oxford: Blackwell.

Larsen-Freeman, D. 2010. ‘The dynamic co-adaptation of cognitive and social views: A Complexity Theory perspective’. In Batstone, R. (ed.) Sociocognitive Perspectives on Language Use and Language Learning. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hi Scott-

What a great post.

I love examining language as it evolves throughout history, all the while noting the uniqueness each user brings to it. Sociolinguistics. If only I could start all over… that’d be it. I majored in sociology, french, and italian, but had I known I could do it all in one, and then keep studying… hindsight, hindsight.

It seems to be part and parcel of modern culture to want to freeze everything and place it conveniently in a box (hence the FIN in deFINition). Nature runs contrast to that, though, and that’s why being awake to the present moment in life, and in the classroom is so important. I’d even say “now more than ever”.

Cheers, Brad

Thanks, Brad, for your comment. For a readable account of language evolution, see Guy Deutcher’s The Unfolding of Language (NY: Metropolitan, 2005). The fact that language is dynamic at so many levels – the global, local, and individual – means that it really is a moving target, and this provides both challenge and excitement for those for whom it is their bread-and-butter!

Thanks for the recommendation ! It’ll be on the fall reading list.

I think the mistake-error distinction is an important one. Errors are often when a person simply doesn’t know the correct form and so they mangle an attempt at it. Whereas the mistakes are more like slip ups.

I’ve noticed when I’m speaking in class that sometimes a few non-standard or ‘chinglish’ forms will start tripping off my tongue and it’s not worth correcting myself usually. And you’re right that a person’s idiolect is inherently filled with mistakes, which are not as noticeable or heinous as blatant errors which break the fundamental rules of the language.

The standardisation of the language came after Shakespeare. That’s when the prescriptive and synthetic rules were invented by scholars in attempt to emulate the regularity of Latin and fashion English into a truly imperial language.

But what are ‘the fundamental rules of language’? Who codified them, and when?

Attempts to ‘standardise’ English probably pre-date even Shakespeare, and were especially pressing (!) once the printing press was invented. Johnson’s was not the first dictionary to prescribe particular spellings, and even Shakespeare’s clumsy typesetters had a notion of what the ‘norm’ was at the time.

The problem is that, if there is a norm, it is constantly on the move, like a flock of starlings: a dense dark centre, a less dense margin, and a few lone outliers.

How do you know attempts to standardise English predated Shakey? AFAIK, linguistic criticism of English is an 18th century movement.

Re fundamentals, I fear I’m going to have to start delving into X-bar theory and other principles of phrasing to answer you. But, I think there is a continuum here, with mistakes at one end like dropping the third person ‘s’ and errors at the other where the semantics of the phrase are at stake.

I think we need to distinguish between standardization and codification. By Shakespeare’s time, the East Midland dialect had become the ‘standard’, due to a combination of factors, mainly social and political, including the influence of the universities of Oxford and Cambridge. That it was the standard meant that Shakespeare himself coud satirize departures from this standard, in the speech of rustics, for example. The standard form didn’t become codified – i.e. written down in prescriptive terms – until a while later, Johnson’s dictionary being a milestone in this endeavour. For more on standardization and codification, see this useful website: http://courses.nus.edu.sg/course/elltankw/history/Standardisation/C.htm

Good distinction between standardizing and codifying. I would add though that Shakespeare was from Warwickshire (W. Midlands) and so he probably spoke with something of a brummy accent and dialect (although Birmingham didn’t really exist then as it does now). We can see an example of his dialect in these lines from Cymbeline.

Golden lads and girls all must,

As chimney-sweepers, come to dust.

‘Chimney sweeps’ means dandelion in the West Midlands.

Oh, Scott, although you are so right, that language is always in a state of flux, I just wish that my trainees whose language analysis abilities are rather shaky and who put together lessons where ‘anything goes’ won’t be reading this post.

(But only this one, as your blog has such great value for experienced teachers and those following DELTA and post-grad courses)

In a similar vein to your questioning post, I remember a great talk by Henry G. Widdowson, delivered a number of years ago – pre Web 2.0 era even. The title was “Real English” and in that talk he proceeded to examine authentic samples of spoken language and discussed whether and to what degree it would be possible for students to ‘make sense of English’ based on analysing these samples. The conclusion he came to should be fairly obvious.

To your question then:

I think language teachers and syllabus and materials designers would have to take account of the current state within the framework of their time but my own feeling is that this kind of information needs to be scaled down – the lower the level, I suspect, the less the open-endedness of language transmitted might be, simply for reasons of what a learner may be able to process at any one point.

The rich and infinite variability of language will, I suspect, begin to emerge once a learner has gone beyond the teacher dependency stage and they begin to become aware of and explore instances of viariabilty in an autonomous way, whether they are still following a course or not.

Thanks for another stimulating post.

Marisa

Hi Marisa, thanks for your comment. Yes, I agree that there is a tension betwen acknowleding the dynamic and changing nature of language use, on the one hand, and the need for relativelty stable criteria of accuracy, on the other. I think it might be possible to accommodate the latter within the framework of what we have come to know as ‘pedagogical grammar’ (and lexis and phonology, for that matter) which is a kind of register that no one actually speaks or writes but which approximates to the dark centre of the flocking phenomenon I mention in another comment. At the same time, we as teachers perhaps need to be a little more tolerant of departures from this so-called norm, given that the users of English (most of whom are not native speakers) are transforming the language – as we speak. The way the flock is restructuring itself is as much due to their momentum as it is to ‘ours’ (meaning we native speakers, not you, of course, Marisa!)

I just wish that my trainees whose language analysis abilities are rather shaky and who put together lessons where ‘anything goes’ won’t be reading this post.

Marisa,

If your trainees are very inexperienced, I imagine Scott’s post may not have much of an impact right now – they will perhaps instinctively feel they have plenty more ‘standard’ and ‘basic’ things to worry about. But even if some of them read the post and it raised pressing questions in their minds, well, this would overall be a good thing, right? Something that you could easily discuss with them and share your take on. Explain the tension, as it were.

🙂

Hmmmm,

I like the metaphor of fish and birds…collectively and mysteriously moving synchronistically, yet individually expressive. I can imagine a speech community as being just one kind of flock/school.

Is there a catch-all mega flock for English that everyone can join?

Are those who stray too far from the flock/school targets for predators?

Migration: dreams of a greener Lingua Franca land? Will those birds

fly back to “Englisher” pastures?

Language change: there’s this mythical bird, “Corpus”, which reigns in the Land of the Probable, far and away from the Land of the Correct.

Hi Scott,

Where does the notion of the norms of “discourse communities” come in?

When I’m teaching my students, I like to think I’m teaching them how to join a ‘discourse community’. Most people don’t learn English for no reason and will probably be learning English to deal with specific situations with specific kinds of people. Each discourse community has its own norms (which change over time) and I see my job as helping my learners crack the codes of this community. This can be as much about appropriate words and phrases as it is about grammar. Even if learning English for travel, we could say that tourists or ‘travellers’ form a discourse community in terms of level of politeness, ways of starting conversations with people on the way etc.

In business, the Plain English movement is starting to make an impact and more and more companies are making using ‘plain English’ a requirement for company communications. Plain English means using phrases like “Let’s sit together and work something out” instead of “I propose we align a meeting to explore possibilities to seek mutually advantageous outcomes”. This comes as a shock to many English learners as they would consider the latter “professional” and the former “too informal”.

Chris

“Let’s sit together and work something out” instead of “I propose we align a meeting […] This comes as a shock to many English learners as they would consider the latter “professional” and the former “too informal”.

Chris, I’ve lost count of the number of times students (in various countries) have been incredulous when informed that a particular ‘formal’ expression is hardly used nowadays. Just this week, in Turkey I managed to make some students’ heads explode by showing they don’t have to use May I…? to make a question ‘polite’, but they can just as well use Could I…? or Can I…? or other variations they hadn’t considered.

Aside from this was the slightly embarrassing spectacle of a fellow Turkish EL teacher constantly addressing me Sir! when he wanted my attention. I was more than happy to tell him that even people who have the official title Sir often hate people to call them by it these days!

Yes, it’s hard for our learners to accept that English changes and those long-cherished phrases and expressions are no longer ‘in’.

In a business setting, many people feel very scared of using newer, easier-to-understand sentences because they were taught to use the more complex forms when they first learned English.

My wife is a Nepali/Chinese translator and she needs to spend lots of time keeping up to date with how the Nepali is changing, and what English words are becoming part of every-day usage there.

By the way, addressing a man as “sir” is quite normal in Nepal, but I’d definitely advise a Nepalese student to stop saying “Sir” if they went on a trip to Britain. What about the US? I hear “Sir” is quite often used between strangers over there, where Londoners and Australians would say “Mate”.

Yes, absolutely, Chris. The fact that some Americans may casually use ‘Sir’ when being polite seems to highlight a cultural difference (at least in certain communities) with current British usage.

If indeed learners make (or discover) the rules by playing the game, one of the most important questions is surely ‘where do you want to play the game?’

There’s no easy answer to the problem you pose, Scott, which doesn’t, of course justify ignoring its existence. There is a very good article on p4 of Learning English, the ELT monthly supplement of The Guardian Weekly (GW July 8, 2011.)

The article is called ‘Bring chaos theory to your teaching’ and it is written by Maurice Claypole, the author of ‘The Fractal Approach to Teaching English as a Foreign Language’. Fractals are a mathematical construct that shares certain traits of human languages such as constant change within the framework of self-organisation. Human languages, Claypole tells us, change dynamically not unlike the weather.

A fractal approach to ELT “concentrates on creative output rather than on a fixed initial state of the language”. So it’s not so much how well you can imitate attested examples of what others have done (much in vogue thanks to corpus linguistics), but what users can do with the potential the system offers them. “Above all, the fractal approach favours a goal-oriented method of teaching combined with a holstic view of language acquisition. It encourages students to explore new paths and expand their language skills by discovering new aspects of English through pattern recognition rather than static language acquisition”.

I don’t think this approach willl go down well with established ELT publishers, examing boards, or training institutions, but I’m off to Amazon to buy this book.

Robin

Thanks for making that connection, Robin. Yes, from what I gather from Claypole’s article, he is working within the same paradigm as Larsen-Freeman and Nick Ellis, i.e. complex systems theory, which embraces the related fields of chaos theory and complexity theory, a core principle of which is that language, like other complex systems, is an emergent and self-organising phenomenon, and that, as Larsen-Freeman is fond of quoting, “you make the rules by playing the game”. This is well illustrated not only in the way that Shakespeare’s language reflected the language of his time (and its transitional, dynamic nature) but also in the way that he changed that language – his original wordings (like ‘brave new world’ or ‘to be or not to be’ or ‘thereby hangs a tale’) reproducing like fractals, until they permeate every discourse community on earth! We can see the same thing happening with catchphrases like ‘I’m lovin’ it!’, and a fractal perspective on ELF (English as a lingua franca) would make a very interesting line of research – just to lob the ball back into your court!

I thought you might do this, Scott but I’ll have to read (and get my head around) Claypole before I can offer a fractal perspective on ELF. And of course, the ball is really in the court of those in a position to carry out academic research, which I’m not, although I imagine that as ELF researchers try to dig deeper into just how English does function as a lingua franca, somebody will take up this perspective.

What is increasingly apparent to me as I travel, though, is that ELF is unstoppably emergent and (most probably) self-organising. I’ve just started reading ‘English as a Multicutural Language in Asian Contexts: Issues and Ideas’ by Professor Nobuyuki Honna. It has some very interesting examples of a range of Asian Englishes ’emerging’ with their own flavour and organisation. Also interesting is that it insists from the outset that using ELF means dealing with variety. Chapter 3 is about diversity management, which is obviously going to be a critical skill in ELF interactions, and Ch 4 about English across cultures and intercultural awareness. I’m looking forward to these.

But coming back to the Claypole article, his closing remark on encouraging ‘students to explore new paths’ took me back to the 3rd International ELF conference in Vienna in 2010 where Henry Widdowson likened ELF usage to ways of crossing an area of grassland between two villages. Anyone wanting to cross from one village to the next when faced with the swathe of grassland would find established tracks (attested uses of English), but that this did not deny them to freedom to take a previously untrodden path, success being measured by their getting to the next village or not.

I guess that what I’m saying is that as a teacher – even though I don’t know exactly how it’s going to be done best – what excites me about ELF is the chance it gives me and my students to exploit the potential English has for creating meaning, as opposed to trying to imitate what others (from other cultures) have already done with it.

Best

Robin

Thanks Robin … both for the Widdowson metaphor of the paths in the grass (I can’t get the image out of my head of Henry, in pith helmet, setting out boldly whither no white man has trod before!) and for these splendid lines:

“What excites me about ELF is the chance it gives me and my students to exploit the potential English has for creating meaning, as opposed to trying to imitate what others (from other cultures) have already done with it”.

All I’d add is that language use is a constant interplay between convention (what people have always said) and creativity (the entirely new), and that Shakespearer knew this perhaps better than anyone.

“you make the rules by playing the game”

I think this is the key point here. I am completing a course with a student at the moment who is moving to London at the beginning of August. Her level is around about C2, pretty darned good, but has had the typical, to coin a phrase, “Cambridge English Experience”:

“Hello, Jane, how did you get on at the office today?”

“Great, thanks Jim, the boss really liked my proposal…” (etc. etc. ad nauseam)

Even at CPE level, this in no way prepared a very dear friend of mine from Buenos Aires, who spent her first week in London in tears and thinking that she’d wasted a lot of time and US dollars on learning English.

Instead of this, I trawled the internet for ideas and was thrown the unlikely lifeline of Jamie Oliver, with his glottal stops, yod-dropping and double-negatives strewn higgledy-piggledy throughout his discourse: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x44WuD_qWsU

And despite all these ELT “evils”, it is just this variability which I think will help my student more that a whole library of CPE listening ever would.

I’ll tell you when she gets back!

Playing the game. As above, this absolutely encapsulates the way to use the language being learned. Of course, it needs the learner to have progressed to a point where enough of the rules have been assimilated, but is an excellent way to think of the eccentricities and innovation that is possible within language use as acceptable.

I have always found it quite extraordinary that native speakers are allowed to bend, play and adapt the language, but any such behaviour on the part of non-native speakers is so often deemed to be error.

Long live the state of flux. It enriches the language, keeps it alive, relevant and fun.

Thanks, James. How can we encourage examination bodies to celebrate ‘the flux’ and become more tolerant both of interlanguage, non-standard varieties, and ELF?.

Or should we just tell them to ‘get fluxed’? 😉

We can’t! Sadly… I suppose there’ll always be the need for a benchmark.

But that’s hardly new nor the end of the world. It’s more a question of exposing our leaners to the nature of real language use – I’m talking about the way language is spoken, I suppose, more than it is written.

It’s why the IELTS listening exam has the edge on the CPE etc. for me – ok you only hear the recording one (COMPLETELY unrealistic) but at least you have to catch numbers, times, dates – all beset with the demons of connected speech.

But it still ain’t the real deal…

As long as there is anything set up as an institutionalised language method, there’ll be a need to formalize “the way” it’s produced. In the meantime, let’s watch more “Jamie’s Ministry of Food” and read more David Lodge. Innit.

Scott, how about dragging them outside their ivory towers and showing them a little of the world we see.

New thinking on assessment is my area of quiet research. I’m wondering what potential there is for an assessment schema or framework that takes account of these variations and can assess them as valid or valuable, rather than holding up an Oxbridge prescription that evaluates ‘good’, as spoken by less than 10% of British native speakers.

Assuming, of course, that such a tool is possible or that its merits would be appreciated by the wider teaching community, rather than shot down by the prescriptivists.

Hi Al, James, Scott,

Yes, playing the game is the key aspect here for me too and I think this attitude to our students’ production is a healthy way of helping us to improved error correction as well as keeping our students motivated to take risks with language.

Instead of jumping on any mistake they make and reformulating it into course book English, we should negotiate meaning with them, ‘are you trying to say this?’ or ‘do you want to say this?’, or ‘I don’t get what you’re trying to say there?’, or ‘what you’ve said there means X to me, is that what you meant?’ to show them what effect the language choices they’ve made have on us as listeners rather than telling them they’ve made mistakes.

This may also help us to be more positive in our correction and also allow us to hear more unintentionally innovative uses of the language that the students would prefer to know how to say in less creative ways.

Hi Scott (and everyone)!

I am a regular reader but this is my first contribution to this blog. Thanks for your post because I was aware of linguistic variability in many areas (such as vocab) but I hadn’t thought a lot about grammatical variability. I wonder, however, what type of grammar and grammar rules we are talking about. In this sense, I can think of many sentences that break “mcnuggetsy” rules (I’m loving it, as you suggest) but I’m not that sure I can think of many exceptions to the rules of cognitive grammar. Within this frame, “loving” might be interpreted in the sentence above not as a lasting state but as a temporary one (Radden and Dirven (2007, p. 193) give other examples of this phenomenon such as “I’m liking my job better and better every day”). If we understand form as inextricably linked to meaning, changes in grammar will translate into changes in meaning. Hence, our importance as course designers, language teachers: rather than telling learners they made a mistake (because “love” is a stative verb and they can’t use the progressive), helping them realize that if they use “love” in the progressive it means something different. Thanks again (Scott and everyone) for your posts.

Best,

Miguel.

Thanks, Miguel, for your thoughtful comment.

I totally agree that the changes we witness in grammar are the result of forms being co-opted to express meanings in ways that are consistent with existing grammar. The use of ‘loving’ in ‘I’m loving it’ is perhaps less a change in grammar than in vocabulary, in that it confers to the verb ‘love’ a dynamic sense that it didn’t always have (and may have something to do with the late twentieth century permissive society, which construes ‘love’ no longer as an all or nothing phenomenon!).

In time, however, a lot of lexical changes of this nature might have the effect of ‘tipping’ the grammar in such a way that simple forms gradually (or suddenly) disappear, having been supplanted by progressive forms entirely.(There is tendency in this direction in Indian English, I suspect). Then new forms will need to be enlisted in order to maintain the distinction between stative and dynamic, much in the way that, in and around Chaucer’s time, ‘do’ was enlisted to reinforce the causative nature of many verbs that perhaps was felt to have been lost (“Do stripen me and put me in a sacke/ And in the nexte river do me drenche” (Chaucer: The Merchant’s Tale) , and then became the delexicalised auxiliary verb that is now the bane of our students’ lives!

This is what Susanne Ehrenreich wrote in a recent article entitled English as a Business Lingua Franca in a German Multinational Corporation:

“Learning to cope with the challenges of such diversity, in the context of business communication, seems to happen most effectively in business “communities of practice” rather than in traditional English training.”

(Ehrenreich, S. (2010). Journal of Business Communication, 47(4), 408).

In other words in the “real world” people are learning by doing, rather than by being “taught”.

Interesting post and again very linked in to what’s happening on my CELTA course as we speak.

It was only today while looking at state verbs we had a discussion about “understanding” as in “I’m understanding you” One or two people on the course said they wouldn’t consider that incorrect as they can think of situations where it might be used. (They were the Americans interestingly)

V is for variability and we haven’t even touched on phonology! With a New Yorker, Californians, Irish, Australians, English and Swiss on this course the diversity in sounds and in some cases word stress is just incredible.

Steph:

GLORY be to God for dappled things—

For skies of couple-colour as a brinded cow;

For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim;

Fresh-firecoal chestnut-falls; finches’ wings;

….

All things counter, original, spare, strange;

Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?)

(Gerard Manley Hopkins)