I’ve just come back from Poland where I gave a series of workshops on grammar teaching, one of which was called ‘Getting the feel for it’, and in which I told this story:

I was once teaching a group of fairly advanced students and the ‘structure of the day’ was gradable vs ungradable adjectives (of the type angry vs furious, hungry vs starving, cold vs freezing etc) and, specifically, the intensifying adverbs (extremely vs absolutely) that they collocate with. Not sure either of my ability to establish the difference nor of their existing knowledge of it, I decided to test the students first, and asked them to decide which intensifier (extremely or absolutely) went best with each of a list of adjectives, some gradable, some not. Unsurprisingly, perhaps, when I checked the task, most of the students had most of the answers correct. “Starving?” “Absolutely.” “Hot?” “Extremely,” etc. “How were you able to do that?” I asked at one point, fishing for the rule. Whereupon one student answered: “It just feels right”.

“Great,” I said, “you just saved me the trouble of having to teach you something!”

“It just feels right”: isn’t this, after all, the ideal state we want our learners to be in? To have the gut-feeling that it’s not “How long are you living here?” but “How long have you been living here?” and not “I like too much the football” but “I like football very much” – irrespective of their capacity to state the rule. This is what the Germans call Sprachgefühl – literally ‘language-feel’: a native-like intuition of what is right.

So, how do you get it? Proponents of the Direct Method would argue that instruction only in the target language is the pre-condition: any reference to, or acknowledgement of, the learner’s L1 would threaten the native-like intuitions that an entirely monolingual approach aims to inculcate. Total immersion is an extreme version of this philosophy.

In the same tradition, but coming from a humanist point of view, Caleb Gattegno believed that – in order to get a feel for the target language – no amount of telling or of repeating or of memorising would work. Instead, learners must develop their own ‘inner criteria’ for correctness. In order to do this, they would need to access ‘the spirit of the language’. And this spirit was to be found in its words – not the ‘big’ lexical words, but the small, functional words that – in English at least – carry the burden of its grammar:

Since it is not possible to resort to a one-to-one correspondence, the only way open is to reach the area of meaning that the words cover, and find in oneself whether this is a new experience which yields something of the spirit of the language, or whether there is an equivalent experience in one’s own language but expressed differently (Gattegno, 1962).

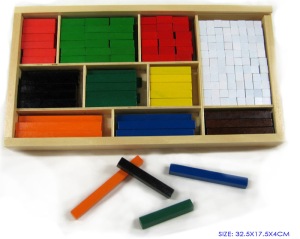

In the Silent Way, then, learners engage with a relatively limited range of language items, initially, but with a great deal of concentration. Concentration is facilitated through the use of such tactile devices as cuisenaire rods (see this comment in the last post on Body).

Subsequently, Krashen (e.g. 1981) would argue that a ‘feel for grammaticality’ cannot be learned; it can only be acquired. That is to say, it can only be internalised through ‘meaningful interaction in the target language’ (1981, p. 1). Later still, the argument as to whether explicit knowledge can be converted to implicit knowledge, and by what means, has exercised the likes of the two Ellises (Rod and Nick), among others. Does practice induce it? Is exposure the trick? And how do you test for it? For example, do grammaticality tests (in which test-users simply decide which of a list of sentences are acceptable or not) provide a reliable measure of Sprachgefühl? And can learners eventually forget the rules they once learned, and function solely on feel?

Finally, connectionist models of learning suggest that feel is simply the effect of the strengthening of neural pathways that results from repeated firings across the mental network. This argues for massive exposure, coupled with continuous use and feedback: it’s really total immersion all over again. For many learners, of course, this is simply not possible. So, how else can they get a feel for English grammar?

References:

Gattegno, C. 1962. Teaching foreign languages. The Silent Way.

Krashen, S. 1981. Second Language Acquisition and Second Language Learning. Oxford: Pergamon.

This is an interesting topic and something I’ve been thinking about a bit recently, especially in regards to my own language learning experience with Polish.

The conclusion I’ve come to is that it’s difficult to envisage how learners can develop ‘feel’ without anything other than massive exposure to comprehensible input in the target language. With regards to English, the proliferation of downloadable learning materials to be found on the internet gives those with access plenty of opportunities to start developing ‘feel’ in English. Of course, this also has the negative impact of increasing the gap between the haves and have-nots.

However, as a starting point, we as teachers can do a lot just by encouraging our learners to stop thinking of language as a set of rules which are right or wrong and start thinking about what sounds more natural. Obviously, for logical learners who like to analyse language this can be a bit of a struggle but I think it’s an important step for learners nonetheless.

One way we can help do this is by encouraging our learners not to translate phrases and structures from L1 into English, which although often not grammatically ‘incorrect’ don’t usually sound like natural English either. I’ve also always thought that a strong focus on collocations as well as fixed and semi-fixed phrases can help get students thinking about what ‘feels’ more natural and what doesn’t.

When it comes to testing, the grammaticality tests that you mention do seem fraught with problems. Isn’t there a danger that these tests could be a little bit too subjective? What would be the criteria for whether a sentence is acceptable or not? Corpus data? And if so, how many uses would a phrase, sentence or structure need to make it acceptable?

Thanks for the comment, Peter. Yes, grammaticality tests – of the type beloved by Chomsky-ites attempting to prove that native-like competence (aka feel) could not be learned simply from exposure – invariably consist of invented (and fairly improbable) sentences of the type: John asked Bill to take a photo of himself. The cat the dog the mouse scratched chased bit me.

Mind you, the wonderful activity, Grammar Auction, as described by Mario Rinvolucri in Grammar Games (CUP) is really nothing more than a grammaticality test turned into a competition.

I’ve always wondered about when this ‘feel’ for the language begins to set in. I teach a groups of A2 students and CAE and Proficiency. I’ve always been struck by the fact that my A2 students don’t seem to have a ‘feel’ for any aspect of the language – I mean they would never answer ‘because it sounds right’ or ‘it feels right’ about anything, even aspects of grammar or vocabulary that they are very familiar with. It’s like the Sprachgefühl develops much later and as a general sensation, rather than for specific aspects of the language as a learner goes along.

But then that’s a question that has always puzzled researchers: when and how does explicit knowledge become implicit?

Thanks for the comment, Eoin. Yes, the question “when and how does explicit knowledge become implicit?” is perhaps one of the biggest conundrums in SLA. As with anything related to both language and the mind, the answer is bound to be provisional, inconclusive, and contingent – that is to say, so much will depend on a) the language item in question; b) the learner; and c) the learning context. Thus, for learner A, learning item X, in context β, explicit knowledge may become implicit, but for learner B, learning item Y, in context α it will not. Which doesn’t really help the teacher much, does it? (Let alone the coursebook writer).

Hi Scott,

I enjoyed your talk in Warsaw, and I enjoyed meeting you at the break—thanks for the reading list and for directing me to this blog.

As for “feel”, I have noticed that learners who can absorb the language in chunks, rather than learning isolated words and grammar rules, and who can accept the fact that word-for-word translation is impossible, seem to develop this feel faster. The seem to be able to “let go”, rather than looking for and depending on a specific rule for each instance of language use. This is harder for older adults, whether because of their age or their experiences with rigid methodologies in Communist-era schools, I am not sure. These older adults seem to persist in their errors much longer, e.g, using the literal equivalent of Polish prepositions like “I parked my car ON the space,” etc., and they don’t seem to be able to enter into the “spirit of the language”.

My own experiences seem to agree with much of the theory you presented above: I developed near-native fluency in Spanish by “feel”. This “feel” was the result of immersion in a discourse community: a rural Central American village where I was the only English speaker above an elementary level. For example, I found myself using tricky subjunctive “chunks” in the same contexts where I had heard others using them: “Ojalá que fuera…,” “Si yo hubiera…,” Looking up the rule in a grammar didn’t seem to help until these structures started to emerge, tentatively, in my own speech in those familiar contexts. At that point, I looked up the rule again, and I felt something click: I could start to use the structure confidently, and in unfamiliar contexts.

Now, I don’t seem to be on the way to near-native fluency in Polish, because of my isolation from the local culture, working and socializing with mostly fluent English speakers. However, I have noticed that massive exposure and need are contributing to my feel for Polish: I learned the Polish instrumental case by feel; it’s relatively simple and it is used commonly in menus and on the packaging for food. The Polish locative case seems devilishly complicated to me: I remember that the inflections are supposed to depend on gender, number and whether the noun has a “hard” or “soft” stem. This case almost always accompanies the most frequent word in the language, the preposition “w”, so recently I started keeping a little notebook with “w” concordances. People tell me that I’m starting to use this case correctly, which suggests the importance of attention (one of your themes). It also suggests that it might be time for me to go back to the grammar reference and look up the rules for the locative case again!

Thanks for your comment Mark – and nice meeting you in Warsaw. Your strategy – of keeping a record of occurrences of key words in Polish, and their immediate contexts – seems to me to be a good one, especially if supported by periodic visits to a grammar or dictionary to confirm (or not) your own hunches. The challenge then is to persuade students of the usefulness of this strategy.

Scott,

What a great title for this post. You couldn’t have chosen something better for letter F.

When I began to read your post and came across the “getting the feel for it” phrase, I immediately thought of gradable and ungradable adjectives, just to discover, a few lines later, that this was the experience you’d had as well.

So, while it’s true that the feel vs. know / feel = know / feel + know debate is far, far from settled, I think there might be three factors to bear in mind here:

1. The “structure of the day” itself

In my experience, it seems that certain structures / lexical areas are more “intuition-friendly” than others. Three examples off the top of my head: gradable/non-gradable adjectives (I’ve rarely had to “teach” them formally, too), subject/object questions (Who did you see/who saw you? – my students seem to have trouble with the former rather than the latter), use/omission of the indefinite article to generalize (which is maybe a classic example of how unteachable certain things are).

2. The learners’ mother tongue (Can of worms alert! Can of worms alert!)

In my experience, certain (but not all) structures that are very similar to Portuguese require far less explaining and analysis than others. Case in point: the difference between simple present / present continuous (which, for some reason, has become a staple textbook item since Headway came along). Whenever I’ve had to teach these lessons, students somehow already know the difference and, though I could be wrong, I’d put this down to positive L1 “interference”.

3. The recognition/production conundrum

Still on present simple… ask a Brazilian low intermediate student to rate a series of sentences for correctness and he/she will probably be able to spot most of the missing third person Ss (unless there’s an adverb between subject and verb, somehow breaking the “musicality” of the sentence). Now, despite the feel/awareness, all this intuition is unlikely to cross over into spontaneous production consistently, I think – not until at least high intermediate level, anyway. So maybe “recognition feel” and “production feel” ought to be treated separately?

4. The lexical items within the structure. Here’s something that’s always intrigued me. When teaching/eliciting the comparatives, for example, some students will intuitively know cheap/cheaper, old/older, young/younger. However, new/newer, for example, will have them frowning because it “sounds odd”, they say. Same applies to play/plays, work/works, like/likes, see/?. Since there’s nothing intrinsically odd about “newer” or “sees” could it be that it’s all due to lack of exposure (we do hear “older/younger” and “likes/plays” far more often “newer” or “sees”)? Could it be than when assessing the “correctness” of a sentences, students are drawing on generative rules far less often than we may assume?

5. Age and learning style

Could it be that older teens are perhaps more intuitive than adults? That field-dependent students form better overall intuitions than more analytical students?

Thanks, Luiz, for shedding much more light than I managed to, on the factors that are conducive to developing a ‘feel’ for grammar, and for making the distinction between receptive and productive intuitions. A good research question might be: Is ‘receptive feel’ a pre-condition for ‘productive feel’? If so, lots of decision-making at the receptive level (e.g. between sentence pairs that are minimally different but only one of which is correct) may eventually feed into accurate production.

As for your point about cheap/cheaper being intuively more acceptable than, say, new/newer, I suspect that this may have something to do with the phonotactics of English, i.e. the acceptable sound combinations and their relative frequency and salience. Adjectives that terminate with a plosive (like cheap) are probably more common than those that end with a vowel (like new), and, moreover, provide a phonetic environment that highlights the addition of a suffix (-er). For the same reasons, a verb like started probably sounds more past-tense-ish than a verb like worked, if only because of the extra syllable. I don’t know any research that has investigated this, but a lot has been done on the way that the meaning of different verbs (their ‘lexical aspect’) influences their selection for tense marking. Stative verbs, for example, tend to be marked for past tense much less, and much later, than dynamic verbs.

Scott,

I had never really stopped to think about the phonetic environment provided by different kinds of words. Thank you!

Luiz, interesting last question about teens… as a Canadian teen, I found that when spending time around Americans I would unconsciously start imitating the accent they used. As an adult in Spain, I maintain my accent. (Even when I speak Spanish…)

Great topic!

Hmm…feel…I notice that my ‘feel’ for Spanish goes quite a long way but not far enough…why not?

I ‘feel’ in my bones that exposure to natural language – especially songs, poems, easily comprehensible nuggets (no, not THAT kind), fiction etc are all part of developing a feel for the language. Prototypical exchanges repeated again and again (if you are lucky enough to live in the target-language culture) play their part too.

But that probably isn’t enough for some (for me?), perhaps. You DO need to study language, understand at some conscious (unconscious?) level what’s going on. That must be part of the ‘short cut’ which helps people who are not acquiring an L1 as babies/children (or who are not lucky enough to live in a Central American village!) on the road to ‘feel’. It’s something about the blend, I guess.

(Of course the next question is what kind of a language you are developing a feel for….do you have to be exposed to endless Britishness to have a feel for British English? What about international English? You have to be around it ands get massive exposure? But even then my hunch – it is only a hunch – is that thinking about it is the other side of that coin)

Jeremy

Jeremy,

My own language development is the direct (though certainly not exclusive) result of years and years of language instruction in an EFL setting, so, I, too, feel it my bones, that it probably does help. The question is: What kind?

a. Is it via some sort of noticing/consciousness raising + ongoing exposure to comprehensible input?

b. Is it via noticing + metalanguage-rich language analysis + ongoing exposure to comprehensible input?

c. Is it by learning and using lexical phrases formulaically and then breaking them down into their constituent parts and analyzing them grammatically?

d. Is it a combination of a,b,c above followed by controlled practice?

e. If practice does indeed help, what kind? Is it the gap-fill type? Grammaticization activities? Task Repetition? Chunk repetition? The Penny-Ur kind of drill?

f. If repetition and drilling do help, is it because of their output value or, paradoxically, noticing potential?

g. Or is it via pushed output followed by feedback + subsequent exposure to massive amounts of comprehensible input?

Sure, it all depends on the learner and, sure, the best stance still seems to be one of “principled eclecticism”, but these shouldn’t be excuses for ELT not to look into these questions perhaps a little more systematically than it has over the past few years.

A question: When does the “F” for “Feel” turn into “F” for “Fossilization”? After 10 years in Chile, and massive amounts of daily immersion, with the occasional Spanish Grammar course thrown in (Intermediate & Advanced – taken 1 year apart) hence exposure, I have achieved the competence necessary to go on job interviews in Spanish, to buy a house, converse at an academic level, yet, my “Feel” sometimes turns into “Frustration” due to “Fossilization” when i find myself outside of my linguistic comfort zone. The Spanish Subjunctive, for example, I avoid with a passion…

I can identify, Prof Baker! The subjunctive is a good example of an item for which I, too, don’t have any intuitions, although I do know that it often follows certain ‘key’ words or phrases such as ‘cuando…’ , ‘no quiero que…’

The two areas in Spanish for which I have absolutely no feel are reflexive verbs (I can seldom predict whether a verb should be reflexive, or, if it is reflexive, what the difference in meaning is from the non-reflexive form) and clitic pronouns, i.e. the ones you add to the ends of verbs, as in ‘pónselo, póntelo’ (a chunk I inadvertently memorised from an advertising campaign promoting contraceptive use some years ago, but which – although internalised – still resists releasing its internal grammar). I guess I should add gender as well – I’m often amazed how I fail to notice the ending on a noun, eg. hijo vs hija, and will completely misinterpret a news story as a consequence.

Hi Scott,

I find that my German (in a Swiss context) flows much more easily, when my mind is open and I “feel” part of the community. For me, nothing slows me down or trips me up as much as continually fretting about whether I should use der, die or das with a word. Too much thinking definitely doesn’t help! That’s not to suggest language can be acquired in ones sleep!

An openness, a receptivity, an awareness of sound, patterns – and a willingness to mimic seem to help in acquiring language. I would suggest language is acquired subconsciously through lots of exposure and natural curiosity (noticing)

A few years ago I took a test and passed B2 level (all gap fills and discrete items) – the way I did the test was to fly through it fast and choose the first answer that felt right. If I started to think too much about the answer, it would become problematic. I couldn’t start to think of rules – because I’ve actually never learned any at all. (I’ve learned all my German “through conversation and “by ear”)

Interesting insight into intuitive learning, Steph. The implications for teaching are, of course, not entirely clear: should the teacher insist on accurate use of der, die, das etc from the outset, or not worry about it until later on. On the other hand, if you leave it too late, the incorrect usages might fossilise.

But that is a good point about trusting your intuitions in an exam – so long as the exam hasn’t been deliberately devised to sabotage your hunches by including rarely encountered exceptions!

Hi Scott,

Thank you for the inspirational workshops in Warsaw – great meeting and talking to you. I’ve just read this blog post as well as all the great comments and I’ve thought about some other ‘F path’.

The receptive/ productive intuition point is a great one. However, I keep wondering if the feel for language contributes only to the higher level students. When it comes to receptive intuition, probably the beginners just need to learn and follow the rules. What about productive intuition for the language of the lower level students or, what interests me the most, young learners? As examples are always appreciated, I can easily recall a lot of situations in the YL classroom when, I believe, some of my students have proved the feel for language. During oral production at ‘sentence level ‘ utterances like ‘I can swimming’ or ‘ I like swim’ just sound wrong to some students. They immediately correct peers without analyzing it. Is it just an example of the immediate usage of fossilized in the brain grammar rules or – do they have the beginner/ elementary level of the feel for the language?

As far as learning Polish (with all the inflections depending on gender, number, the cases, surprising exceptions to anything etc. ) is concerned – there’s a secret I am going to reveal which Peter Fenton and Mark Leonard may find as an additional motivation. I believe, there are not many Polish people ( great linguists and Polish language enthusiasts ) who may say their Polish language production is 100% grammatically correct. The rest of us – just depend on the FEEL for the language.

I’m wondering..if it is the case with all the languages. However, feel for the grammatically correct native language production is, I believe, another great area of investigation.

Ps. Thank you for making me realize that in order to FINALLY FEEL Spanish language I have to FINALLY make use of the book I’ve bought recently – ‘ Spanish Pronouns and Prepositions’. That’s a great side benefit of your Warsaw workshops.

Ania

Thanks, Ania! I don’t think native speakers of Polish are unique in not knowing – consciously – the ‘rules’ of Polish, or of breaking them regularly: that seems to me to be the definition of a native speaker of any language – that they are generally incapable of articulating their L1 knowledge in metalinguistic terms, but always know when something is incorrect because ‘it feels wrong’. (With the proviso, of course, that they might not know or obey all the prescriptive rules of the language, as codified in style guides, for example).

I also think that children are probably more amenable to ‘learning by feel’ – in fact, it’s unlikely that they have the requisite cognitive faculties to make sense of grammar rules until they’re at least 10 or so. Whether they lose this capacity is a moot point – Steph’s story (above) about her German suggests that even adults can ‘acquire’ a second language and know, intuitively, what is correct, even if they have never studied it.

Scott,

I’m not really sure you can “teach” this but yeah, massive exposure/immersion does produce a feel (and too at times, that “sinking” feeling” – works both ways).

My “feeling” (forgive the pun) is that this has to do with the sounds of a language and their relationship to meaningful chunks. It is standard to assume that there is no relationship between the sound symbols/signs and the meaning of the utterance. However, I’m not so sure that this crusty linguistic principle is true. As a poet and someone with Foerster’s syndrome (being overcome with language and a need to pun!), along with knowledge of quite a few languages – I really see that there are universals in sound/meaning connection. The guttural “U” is common in most languages for disgust. “L” is denotes a sense of flow and tranquility. I could go on – the best reference for this is a long forgotten “linguist/surrealist” William Blood and his Poetic Alphabet. But my bet is that a feel for language is the feeling that there is a correspondence between sound and meaning in words/sentences. Students can “feel” because sound has its own denotation and meaning.

That’s what I think is going on. PS. please see the new Google tool – http://ngrams.googlelabs.com I know you’ll be interested in this given your interest in corpora.

Thanks David. You comment comes at a time when I am grading my Masters students’ final assignment, which involves a contrastive analysis of negation and question forms in English and a language of their choice. I was struck by the number of languages (including Englihs, of course) whose way of negating a verb or verb predicate involves some word or particle or affix that includes the sound /n/. I wonder if this is an instance of the kind of phonetic universals you are talking about?

Scott,

I have a long list somewhere – I once attempted to write an “Idiot’s Dictionary” and this list was part of it. ex. Fit (thin “i”) Fat (fat “a”) or slit/slat/slut to give you an idea. Sound as well as fury, has meaning. However /n/ never made my list. There are many languages that negate with this sound but then there is Korea which uses it to affirm! But in general, you’ll always find exception (time the destroyer does make for this) however it doesn’t negate that this might be the case. Glad you don’t think it wacko (like a quite well known prof. of mine when I brought this topic up my phonetics MA course. ) He was firm that the relationship between sound and meaning is purely arbitrary (but we believe what we are taught – don’t we? ).

But it is an interesting area – wish I was young enough to tackle it rather than just play around with the notion thereof….

David

Thanks for another fascinating post Scott and for all of the interesting comments.

Luiz’s comment got me thinking about a strange phenomenon that I’ve noticed from some of my students here in Jordan. One particular instance that rings a bell is when I was teaching an older gentleman some grammar rules about the simple present and the present continuous. This student was already strong at using the rules from his “feel”, since he had had a lot of exposure to English along with years of using the language for work. However, when I went into the rules, I discovered that he couldn’t successfully complete the usual fill in the blanks exercises that follow the grammar presentation in many coursebooks. To increase my sense of horror, he started bumbling up the simple present and the present continuous in his speech, something that he generally didn’t do before we studied the rules in the coursebook. His fluency when using the simple present and present continuous was also adversely affected. I’ve experienced this with a few other students as well.

Is it possible that overtly going over grammar rules and doing some of the grammar exercises in books can actually be deleterious to one’s “feel”?

Is it possible that overtly going over grammar rules and doing some of the grammar exercises in books can actually be deleterious to one’s “feel”?

Well, I’m glad you said it and I didn’t! (Or else I’d have Jeremy on my back for starters). But I’m inclined to agree. Certainly, an obsession with teaching rules – at the expense of time spent on communicative use – might prejudice certain students from developing their own intuitions.

How can it be wrong when it “feels” so right…?

The flipside to “feel” is that it’s sometimes just that: wrong. In the CAE exam, the multiple choice cloze exercise challenges learners to select correct collocations from a choice of four. I’ve had plenty of learners say to me, on learning the correct answer, “really? It doesn’t sound…”, (i.e. “I didn’t choose that option because it sounded wrong”).

Whilst I always tell them that their “feel” (I call it instinct) is often the best indicator of the correct answer, they need a backup for this and, as we CAN help them, we SHOULD help them.

So I wouldn’t bin a lesson on gradable/ungradable adjectives because students perform well in an initial diagnostic: I imagine at least some of them wouldn’t necessarily know WHY they were getting the answers right and there are reasons: and in my experience as a student of Spanish, I want to know WHY things are as they are.

I also imagine that “feel” isn’t going to help learners at this level distinguish between horrors like “heavily polluted” and “highly polluted”: such collocations don’t come with the free gift of “feel” and we’d do our learners a disservice by ignoring this.

And it’s too easy to say that we’ll give them “massive exposure” to the language… will we really? I doubt it. Practicality suggests that this ain’t gonna happen. It also suggests that giving them the tools they need to achieve autonomy is more responsible teaching.

Fair point, and I’m not an advocate of the ‘no interface’ position – i.e. the argument that explicit knowledge can never become implicit knowledge (or that learning can never become acquisition, in Steve Krashen’s terms). On the other hand, if there are no, or few, opportunities for use, then there is a good chance that there will be little or no transfer – generations of school children who have learned the rules of a second language but who – after six years – are incapable of answering the question ‘What’s your name?’, if sprung on them, would seem to bear this out. Not that you’re suggesting this, of course, but my feeling is – if the learners can come up with accurate production on the basis of ‘feel’, then great – let’s move on to something that DOES need to be taught.

Yes, the intutition is vital, I just think it has to go in hand with the reasons WHY the intuition exists – it exists for a reason, be this instruction or repeated exposure to X language point.

And learners want to know why too! And yes, once we’ve done that (or they’ve done it for themselves), let’s move on to… inversion or something.

A subject near and dear to my heart. You are brave to write about it, because “feeling” is, by its very nature, fuzzy and ill-defined; the antithesis of the hard, fast conclusions required by “methods” and “approaches.” Yet most learners of any L2 will agree that “feeing” for “what sounds right” is a vital component of confidence and, eventually, competence in the target language. I have to come down in favor of exposure (“sounds right” really says it all) as the key ingredient here. I often see EFL learners with relatively little formal instruction but good amounts of exposure (usually from illegally downloaded English-language films and TV series) show a sophistication of usage far in excess of what one might expect; whereas we all are familiar with the learners with 8+ years of classroom English under their belts that still struggle with basic grammar and have a fairly limited “common usages” vocabulary. There is a parallel with “feeling” for math here somewhere (if you do enough math, you start to visualize solutions to equations without having to go through all the intermediary steps), but I guess that could be a whole other blog post! Great topic, Scott.

Thanks Paul – you had anticipated some of the comments I have just made (above). And, yes, I think it is very relevant to generalise about ‘intuition’ from other learning domains, including such skills as playing music or chess. Skill theory would argue that converting declarative knowledge to procedural knowledge, through practice, involves processes of automatization and ‘chunking’, such that the original, declarative knowledge is often ‘lost’, and what is left is fluent (although not necessarily accurate) performance which feels intuitively ‘right’.

Hi Scott,

Personally, I think a fluid combination of exposure, discovery learning techniques, and Swain’s Output Hypothesis all help to promote the “feel” you describe (and that many teachers and learners must have “felt” at some point). One of my favourite refrains in the classroom in Korea was “Gen-to!” (which is a south coast slang term for “guess” inherited from Japanese) – which was a message to learners to “take a punt (or go by feel) and see what happens”.

I also quite like U2’s Bono and his line (from Beautiful Day):

What you don’t have, you don’t need it now.

What you don’t know, you can feel — somehow…

I’ve liked the message in that as a teacher, experimenting with classroom managment and methodology, but also as something to pass on to learners — both as an outcome of the way I teach and as something for them to think about and take away with them.

I was thinking as I read this in the small hours of last night how closely linked Feel is to Body. As I was relying on intuition I struggled to put this into words, but as I am also reading with enthusiasm a book called ‘The Word for Teaching is Learning’ (Heinemann, 1988) I was able to find this morning what I hope is some supporting evidence. In an essay in that book called ‘Listening Learning’, Gordon Pradl remarks that ‘much of our verbal power resides in potential body states.’ By way of example, Pradl cites the way in which we remember key information (for the number of his school locker, read an online password) only when, and often where, we need it – at the moment of need, the words, or numbers, return.

But he also relates the notion of a link between physical state/need and linguistic performance to the work of Daniel Stern on pre-linguistic development in infants, who in Pradl’s formulation experience ‘a natural correspondence between [their] own bodily actions and the attuned responses of the caretaker.’ The caretaker being in this the parent or significant other – and, yes, the better other, who scaffolds expressed bodily need with language. Thus, Pradl suggests, is a foundation established ‘for relating the affective with the cognitive aspects of language. … It is on this basis that we speak of being in touch with our intuitions. We know about the world through words which have been linked with bodily states, and this is what we feel when in uttering an expression we have the sensation of getting it right.’

Happy coincidence, supporting evidence, or a bit of both?

A bit of both, I’d say, Luke! Thanks for that comment and quote, which brings me right back to the Dwight Atkinson article that prompted my original post (on the body), and the concept of alignment: “Alignment is the basis of social life, and beyond that, of adaptivity to the environment. Views of SLA which ignore alignment neglect fundamental aspects of humanity, as well as reasons for which and actions by which a fundamental human activity — learning — must occur” (p.618).

Luke,

Pradl’s examples point to the importance of context in the encoding and retrieval of memory. The examples you cited made me think of some interesting readings and references on declarative memory (1) and context I came across while teaching English to a group of neuroscientists:

“Memory appears to be stored in the same distributed assembly of brain structures that are initially engaged [in perceiving and processing the initial input].” (2) These brain structures that store the separate bits and pieces of your memories are widely scattered around your brain. (3, 4, 5) Some of the studies that showed that context is linked to recall are bizarre indeed. In one, divers wearing wetsuits listened to lists of 40 random words, either on land on in the water. Recall was 15% better if they were in the same environment where they first heard the words. (6) This effect of context on memory happens even when experiencing conditions (marijuana or laughing gas!) or moods that you would expect to inhibit learning: when those conditions are repeated, recall is better. (7)

I’m not a neuroscientist, and I could be reading too much into these studies, but they seem to provide concrete explanations for things teachers have always intuited: Using students personal experiences as material for class is useful because of the context, emotional and otherwise, that the experiences evoke. (Would this evocation of experiences be what Padl means by “potential body states”?) And role-plays and theater are useful because they help provide a more realistic context for later recall.

References:

1 – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Declarative_memory

2 – Squire L & Kandel E (1999)

Memory: From Mind To Molecules

Scientific American Press (NY)

p. 72

3-Livingston, M & Hubel, D (1988)

Segregation of form, color,

movement and depth: anatomy,

physiology and perception

Science 240: 740 – 749

4-Binding, spatial attention and

perceptual awareness

Nature Reviews Neuroscience 4(2):

93 – 102

5-Separable processing of consonants and vowels

http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v403/n6768/full/403428a0.html

6 – Godden DR & Baddeley AD (1975)

Context-dependent memory in two

natural environments: on land and

under water

British J. of Psych 66: 325 – 332

7-Marijuana, laughing gas & mood

Passer, MW & Smith RE (2001)

Psychology: Frontiers and Applications

McGraw Hill (NY)

pp. 291 – 292

Recall was 15% better if they were in the same environment where they first heard the words.

Fascinating findings, Mark – thanks for that. It suggests to me that language should be presented and practised in what Keith Johnson calls ‘real operating conditions’ – that is, in the kind of conditions that most closely reflect those in which that language will be used. Of course, this is not easy to predict, but if – at least – language is learned and first used in conditions that have some kind of personal relevance for the learners, the more likely it will be that they will be able to recall it when they (really) need it.

An interesting look at a fascinating topic. I can remember the exact moment when I started to rely on feel for the first time in my second language (German). It was a year after starting the language at secondary school, and it was in a situation in Germany where I didn’t have time to think. I couldn’t ever decline the adjectives correctly in grammar exercises but suddenly, collecting my shoes from a skate hire shop, I said ‘those blue ones there’ entirely correctly, and experienced a shock of surprise but also recognition – I knew for sure that what I had said was right, but couldn’t have explained why.

From that point on I ignored everything our teacher said (he was using, in the mid-nineties, the grammar-translation textbook he had had at school, printed in 1961) and relied entirely on my feel. I was rubbish at vocabulary tests and at homework and got told off a lot but did learn what I needed for GCSE anyway. Ten years later I was perfectly fluent and since then have often been mistaken for a native speaker. When I later learned Italian, I ignored grammar until I noticed I could do something (e.g. use the imperfect tense) and only then did I do some grammar exercises on that topic. I don’t know why, but it worked for me and I was fairly fluent within two years, without any classes, just with two months of naturalistic exposure in a bilingual Italian-German family and a lot of TV.

I don’t know whether my experiences are generalisable for others. I do know that I now have zero explicit knowledge of German – if you ask me for the gender of a noun, not only am I unable to tell you, but just one question destroys my language feel for some minutes afterwards. I think it’s because I become conscious that I am speaking German, something which I normally do not notice.

I do notice when learning new languages such as Spanish I can switch into them mentally at a very early stage even if it means I have very basic thoughts – or none at all. I also dream in the languages I am learning very early on, even though the dreams are ridiculously limited.

Again, I’ve no idea what any of this means, but a fascinating topic and definitely an area where more research is needed.

So many different and interesting strands to this topic. I like and identify with what Steph says about intuitive learning. I think I got a “feel” for Brazilian Portuguese from 1) having an intensive two-month exposure to the language at the outset and 2) developing a sense of “what felt right or wrong” quite early on. This probably came from my explicit and implicit knowledge of Spanish and a love of Brazilian music.

For example, one of things that I realize didn’t sound right from the start was to say ‘sim’ (yes) when affirming or agreeing. Strange, you might think. But Brazilian Portuguese speakers rarely do say ‘yes’. Instead, they will answer with the same verb as used in the question or use an alternative like ‘é’ (‘it is’) or ‘isso’ (‘that’). I realized how easy it was to mimic this and I did it all the time, I think partly to distinguish it from Spanish in my mind and partly because I enjoyed the mimicking. I thought to myself “this is great, this really feels Portuguese!”. I remember mentioning this to an ex-pat who had been living in Rio for some months but who was not involved in language teaching and he told me that he had never noticed it.

I also identified with what David said: “Students can “feel” because sound has its own denotation and meaning.” Again, returning to my Brazilian experience, I can see this was true for me. It’s very easy (at least for a Romance language speaker) to pick up the words for “good” in Portuguese as in phrases such as “tudo bem”, “¡qué bom!”, they sound at once like they have a connection with ‘good’. But that wasn’t so with one of the most common Portuguese words for ‘bad’: ‘ruim’. Even with the intonation that you’d expect people to use when they say, for example, “that’s too bad”, I just didn’t notice this word “ruim” because it didn’t look or sound to me like it meant ‘bad’ (“ruim” is also very hard to pronounce).

It strikes me, then, that there is a definite skill to noticing, it’s not just about having curiosity. We can do this because as teachers we are constantly on the look-out. Our job should then be to introduce noticing activities explicitly as part of classroom practice so that our learners are then primed to notice in real-life interaction outside class and thus get a feel for what is wrong or right.

Finally, I was interested in what you said Scott about skill theory which “argues that converting declarative knowledge to procedural knowledge, through practice, involves processes of automatization and ‘chunking’, such that the original, declarative knowledge is often ‘lost’, and what is left is fluent (although not necessarily accurate) performance which feels intuitively ‘right’.”

This, to my mind, brings up the importance of language play and the need to allow learners the freedom to experiment and develop their own individual “feel” for a language that may be quite idiosyncratic and particular to them. To give you an example: a friend of mine when he hasn’t heard me say something, rather than saying ‘sorry?” tends to use (what I consider to be) the overly formal ‘I beg your pardon, Ben?’ When I pressed him about this he said that he knows that’s it’s not 100% appropriate but that he tries avoiding saying “sorry” because he can not help rolling the “r” and that makes him sound like a typical Spanish speaker of English. He enjoys being different and saying it this way. By choosing to use ‘I beg your pardon’ he adds a unique touch to his English that feels right for him. He is thus building towards creating his own voice in another language. That’s something to celebrate, I feel.

Ben,

It’s funny you should mention Brazilian Portuguese (my native language). If I remember correctly, ELT first started talking about noticing after the Schmidt article in the late 80s, in which he described his own experience learning Portuguese in much the same way you did. Could it be then that there’s something about Portuguese that tends to make its idiosyncracies particularly noticeable?

But I digress. Whenever ELT hypes up a theoretical construct the way is has hyped up noticing in recent years, I am automatically put on the defensive…

You see, I used to believe that input flooding alone (via readings or listenings or even teacher talk) + the right sort of guidance would be enough for noticing to take place. Well, it might, but maybe it’s not the kind of noticing that prompted you to restructure your own Portuguese interlanguage (or Schmidt’s, for that matter) for one simple reason: genuine interest / curiosity / identification with the target culture.

I was recently working on a sample unit for a new coursebook and I spent a great deal of time trying to find ways to FLOOD the input with the “structure of the day” before the actual grammar analysis. What hit me as I was doctoring” some of the texts is that input salience alone without intrinsic interest on the learner’s part may not amount to much.

The 70s/80s parallel would be the ELT’s blind adherence to information gap activities. I think Michael Swan once said that some of the information gap activities he’d seen recently were SO dull (you know, comparing train timetables of countries students had never been to, exchanging details about made-up characters and so on) that he wondered whether the pseudo-purpose created by the information gap element had any sort of usefulness.

Thanks Luiz – good point about activities that – if they fail to engage learners – will wash right over them. Regarding the Michael Swan reference, in Teaching Unplugged we quote him to this effect:

Yes, you’re right, Luiz. As a teacher, you’re never going to successfully help learners notice things unless you engage them or show your own enthusiasm.

I too despair when ‘doctoring’ texts because there is nothing worse than forcing a structure into a mould in which it doesn’t really fit and then, to make matters worse, obliging learners to notice it. Apart from anything else, the learners get very wise to that. That’s why I like to try and allow that structure to emerge and not go in there with my ‘agenda’, but that’s not always possible of course!

Finally, you’re right that my comments about learning Portuguese were very much influenced by Schmidt’s language autobiography. I understand your scepticism, but what I still find attractive about Schmidt’s ideas about noticing is that element of surprise. In my teaching experience, I’ve found that when learners are primed to notice, they do sometimes notice things that would never have occurred to you and that can be very rewarding

Thanks for the quote, Scott.

There’s something about Michael Sawn’s writing (perhaps the wholehearted belief with which he means what he says?)- that makes his words virtually indelible.

I remember reading his criticism of the communicative approach many years ago (ELT journal or something?) and the way he attempted to destroy the usage / use dichotomy with the burglar anecdote was fascinating and highly amusing.

A good teacher is aware of how much they don’t know.

Like how learners develop a ‘feel’ for the language, for example!

It’s obvious that experts can only speculate to a large degree how ‘feel’ works. No-one has any concrete answers for the teacher in the classroom other than some hazy general principles it appears wouldn’t be detrimental to follow.

Like Scott has said, it may be too difficult in the end to understand (and make prescriptions for) these things at the level of the INDIVIDUAL LEARNER. To state a massive cliche… surprise, surprise… learners are all very much different.

If the teacher, who knows their learners well as people, can only work around general hazy principles – keeping their eyes open, as it were – what chance is there for the traditional coursebook writer? None, I’d say.

Though probably Scott been asked (tempted?) many times, he has been very wise to avoid writing coursebooks (though, of course there was the CELTA booklet – is that a coursebook?) and concentrate more on books like Teaching Unplugged which by their very nature put the emphasis on the people in the room and leave it open for the learner and the teacher to follow their own ‘systems’.

Anyway, back to feel…

There are surely many factors at play here for developing a possible ‘feel’ for a new language. There have many mentions of aspects exposure and of setting, but also doesn’t it help if the learner….? :

– has a strong ‘aptitude’ for language learning.

Give someone a guitar who has no aptitude for guitar playing and they may never develop a ‘feel’ for it. We might as well just bang our heads off the wall if we expect otherwise.

– has a natural ‘affinity’ for the target language.

I’ve met many learners who knew from an early age that they wanted to communicate in the target language. They just liked it and were drawn to it. These guys are the exception in any classroom, but they are most certainly there.

🙂

The following from Tim Murphey’s LANGUAGE HUNGRY might indicate that getting the feel involves a lot of work driven by passion:

What a great quote, Jane. Really pertinent to the Ideal L2 Sef concept too. I’ll definitely be looking this up. Thanks!

‘The feel of a native Spanish speaker’.

The other day I was having a conversation with a non-native speaker of Spanish. When she said, ‘La secretaria le dijo que el ‘no estaria responsable’, I told her that we use ‘seria responsable’ instead of ‘estaria responsable’. She went on arguing about her knowledge of the difference between ‘ser’ and ‘estar’ in Spanish and added that ‘estar’ is used for temporary situations or state of beings and that ‘ser’ is more about ‘essence’. She added that we say ‘esta muerto’ in Spanish because it is also a state of being even if it is irreversible. My daughter was also puzzled by this and asked me, how come we say ‘El esta feliz’ and we cannot say, ‘El esta responsable’? She couldn’t understand because they are both adjectives. It wasn’t until we both consulted our erudite cousin who does literary translations for Random House that we learned the history behind the usage of ‘ser responsable’. My cousin told us that the common usage of ‘responsible’ today denotes a quality that can be learned. We at times may be responsible and at times not so. We hear the teachers in school telling her/his pupils, ‘Tienen que aprender a ser responsables’. However, according to my cousin, ‘ser responsable’ should be part of our essence and it has theological roots. We should be innately responsible because we need to respond to God. This is why in Spanish it is ‘ser’ and not ‘estar’. My cousin also mentioned never to tell a woman ‘estas bella’, as it denotes that she is not always bella and she may be insulted. My daughter said, that is a back-handed compliment! How do you say that in Spanish?

Thought this could come in handy in Barcelona.

Happy New Year!

Carmen Echerri

I’ve learned Japanese and French through the Silent Way and did get “feels” for both. Wish it were easier to find Mandaring Silent Way teachers as I’m in China now.

I’d really like to learn how to teach with this approach.

No to everyone, including you Mr. Thornbury. Sorry. But I deal with the emerging world of ELT, namely “I read it, but I never speak it”. With technology I find that my learners have considerable engagement with English in writing (through websites, emails, texts, tweets, adverts, so be it).

When I think about my language learning experience it makes sense why functionally grammatical particles were lowest on my priority list. I distinctly remember reading the the Süddeutsche Zeitung at German B1 level with my dictionary. What did I look for… content words! Nouns and verbs. I still have considerable problems with der, die, das… but they matter less.

Prepositions, articles, conjunctions, etc. were only filler. To understand the meaning I needed content. When I compare this with my learners they are much the same. Lower intermediate and beginners say, “I need vocabulary!”, higher learners say, “I need prepositions and tenses!”. I was the same.

You have already written about feeling verb tenses (something beginner learners do not notice) and I have incorporated aspects into my training with profound effect. The next step is particles. But we are merely talking about combining them with vocabulary the learners already know.

In other words… draw on the learners’ reading experience to look left and right for functional collocations. Forget teaching verb + prep collocations, they will never retain them and we have better thing to do with our time.